James Reyos — a gay Apache man — was convicted of killing a closeted Catholic priest in a motel room in Odessa. Credit: Courtesy Photo / Night in West Texas

James Reyos — a gay Apache man — was convicted of killing a closeted Catholic priest in a motel room in Odessa. Credit: Courtesy Photo / Night in West Texas

The first time that Allison Clayton, deputy director of the Innocence Project of Texas (IPTX), heard about the murder case that sent Odessa native James Reyos to prison, she immediately knew he wasn’t guilty.

“James had been railroaded by the system for a variety of reasons,” Clayton told the Current during a recent interview. “I was afraid we weren’t going to be able to do anything for him because we have a court system that is becoming more and more hostile to claims of actual innocence.”

In 1983, Reyos — a gay Apache man — was convicted of killing Father Patrick Ryan, a closeted Catholic priest, in a motel room in Odessa. Although Reyos had an airtight alibi, and there was no physical evidence tying him to the crime, he was sentenced to 38 years in prison.

Clayton said to get Reyos fully exonerated, she needed help from a “heavy-hitting journalist” who could expose the cracks in the original investigation. She turned to filmmaker Deborah S. Esquenazi, who had made the award-winning 2016 documentary Southwest of Salem: The Story of the San Antonio Four, which brought national attention to four queer Latinas wrongly convicted of sexual assault.

“I am of the belief that you have to get publicity in these cases to move the needle,” Clayton said. “It shouldn’t be that way. It should be about the law, but it’s not. Our reality is that it’s about public opinion.”

During an interview with Esquenazi, we discussed her new documentary, Night in West Texas, about Reyos’ case, and why she felt compelled to tell his story. Visit nightinwesttexas.com for a list of upcoming screenings, including one at the Lone Star Film Festival in Fort Worth on Dec. 18.

What resonated with you about James’ story?

James’ story was hard to accept. It was remarkable in terms of a man who was framed for what happened when he wasn’t even in the state. And then, of course, with my work, I’m always interested in the complexities of what it means to be queer, especially in the 1980s, and how that might have impacted his trial.

How did you keep all the themes you confront in the film — from sexuality to systematic prejudice — from overshadowing one another?

It’s sort of a two-pronged reality. It’s how I live my life as a documentarian. There are no easy villains and no easy heroes. I think it’s important to be a listener. That’s my job. Then, during editing, it’s about massaging and finessing [the film], so it feels balanced. If we’re trying to reflect any essence of truth, whatever that might mean for somebody, the nuance is critical.

Did you collaborate with consultants during production to ensure you weren’t being exploitative in any way?

In terms of forensics and criminology, we worked with the Center for Homicide Research. After we finished an early cut of the film, we sent it to different indigenous tribes to make sure we were hitting the notes without any exploitation. In terms of queerness, I took that up myself because I am queer, and I feel comfortable speaking on that. Then, we had Allison, who understands the law. And, of course, we had James, who was the biggest source of all. If I had any questions about identity, I just asked him.

What kind of reforms would you like to see happen because of James’ case?

Well, right now, the thing I am really hanging my head about is the shift of the court system towards the right. So, I want the issue of innocence to be a bipartisan issue in Texas. It was for a long time, [but] that part is slipping. That is worrying me more than anything because if we have a system that wrongfully convicts people, we have to have a system that also rectifies and apologizes. I would rather we get it right 100% of the time.

Are you still in contact with the San Antonio Four?

Yeah, Anna Vasquez is actually working at the Innocence Project of Texas. So that’s remarkable. Elizabeth Ramirez came to James’ hearing. We all went to San Antonio together to meet with the San Antonio Four and did some advocacy for James. So, we check in occasionally. I’m delighted that they’re doing so great.

The first time that Allison Clayton, deputy director of the Innocence Project of Texas (IPTX), heard about the murder case that sent Odessa native James Reyos to prison, she immediately knew he wasn’t guilty.

“James had been railroaded by the system for a variety of reasons,” Clayton told the Current during a recent interview. “I was afraid we weren’t going to be able to do anything for him because we have a court system that is becoming more and more hostile to claims of actual innocence.”

In 1983, Reyos — a gay Apache man — was convicted of killing Father Patrick Ryan, a closeted Catholic priest, in a motel room in Odessa. Although Reyos had an airtight alibi, and there was no physical evidence tying him to the crime, he was sentenced to 38 years in prison.

Clayton said to get Reyos fully exonerated, she needed help from a “heavy-hitting journalist” who could expose the cracks in the original investigation. She turned to filmmaker Deborah S. Esquenazi, who had made the award-winning 2016 documentary Southwest of Salem: The Story of the San Antonio Four, which brought national attention to four queer Latinas wrongly convicted of sexual assault.

“I am of the belief that you have to get publicity in these cases to move the needle,” Clayton said. “It shouldn’t be that way. It should be about the law, but it’s not. Our reality is that it’s about public opinion.”

During an interview with Esquenazi, we discussed her new documentary, Night in West Texas, about Reyos’ case, and why she felt compelled to tell his story. Visit nightinwesttexas.com for a list of upcoming screenings, including one at the Lone Star Film Festival in Fort Worth on Dec. 18.

What resonated with you about James’ story?

James’ story was hard to accept. It was remarkable in terms of a man who was framed for what happened when he wasn’t even in the state. And then, of course, with my work, I’m always interested in the complexities of what it means to be queer, especially in the 1980s, and how that might have impacted his trial.

How did you keep all the themes you confront in the film — from sexuality to systematic prejudice — from overshadowing one another?

It’s sort of a two-pronged reality. It’s how I live my life as a documentarian. There are no easy villains and no easy heroes. I think it’s important to be a listener. That’s my job. Then, during editing, it’s about massaging and finessing [the film], so it feels balanced. If we’re trying to reflect any essence of truth, whatever that might mean for somebody, the nuance is critical.

Did you collaborate with consultants during production to ensure you weren’t being exploitative in any way?

In terms of forensics and criminology, we worked with the Center for Homicide Research. After we finished an early cut of the film, we sent it to different indigenous tribes to make sure we were hitting the notes without any exploitation. In terms of queerness, I took that up myself because I am queer, and I feel comfortable speaking on that. Then, we had Allison, who understands the law. And, of course, we had James, who was the biggest source of all. If I had any questions about identity, I just asked him.

What kind of reforms would you like to see happen because of James’ case?

Well, right now, the thing I am really hanging my head about is the shift of the court system towards the right. So, I want the issue of innocence to be a bipartisan issue in Texas. It was for a long time, [but] that part is slipping. That is worrying me more than anything because if we have a system that wrongfully convicts people, we have to have a system that also rectifies and apologizes. I would rather we get it right 100% of the time.

Are you still in contact with the San Antonio Four?

Yeah, Anna Vasquez is actually working at the Innocence Project of Texas. So that’s remarkable. Elizabeth Ramirez came to James’ hearing. We all went to San Antonio together to meet with the San Antonio Four and did some advocacy for James. So, we check in occasionally. I’m delighted that they’re doing so great.

Subscribe to SA Current newsletters.

Follow us: Apple News | Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter | Or sign up for our RSS Feed

Related Stories

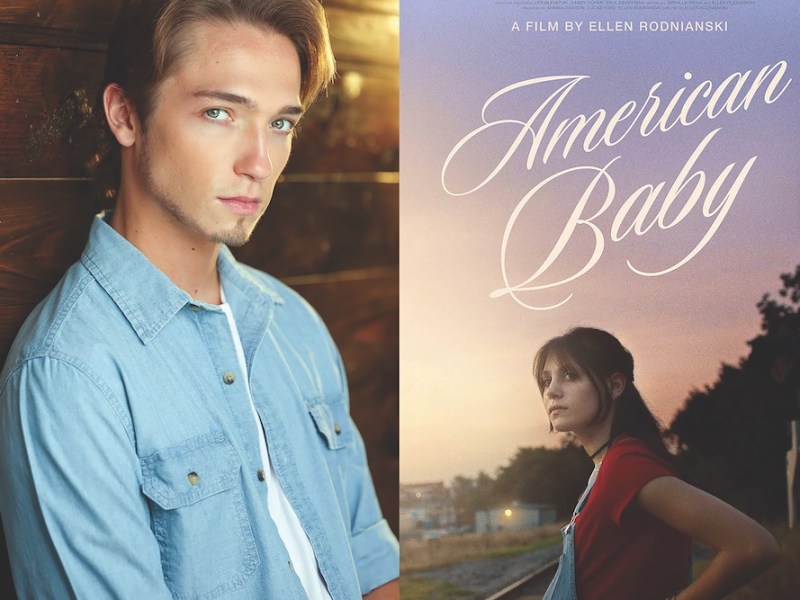

Springer, 22, appears in the feature, which won the Audience Award for Narrative Feature at the Austin Film Festival.

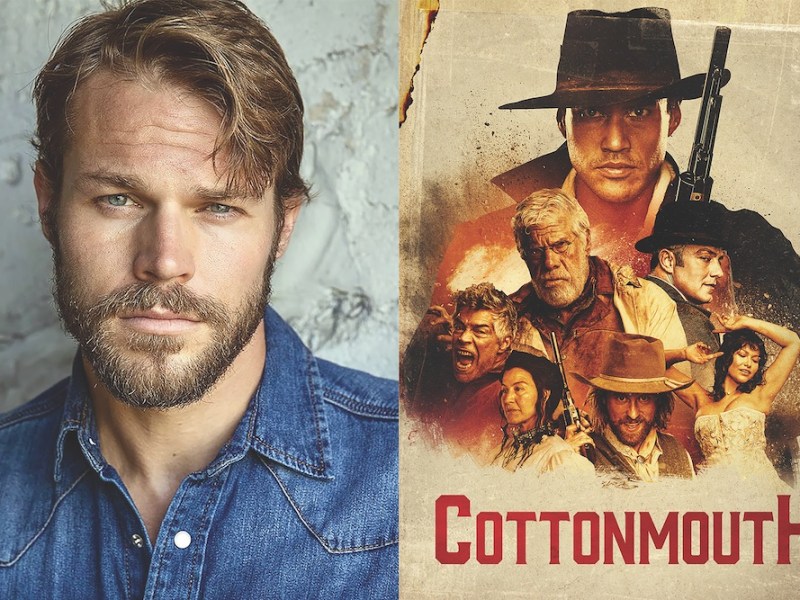

Cottonmouth, a Western adventure shot on an indie budget, is currently available to stream on Prime Video.

The movie, which screens Saturday, is the last installment of this season’s Native Film Series.