Inside the Henry Wade Juvenile Justice Center, the Regulation Room is still windowless and lit by the glare of fluorescent bulbs. But like the rest of this youth detention center, it’s changing from what it used to be.

Not long before juvenile services director H. Lynn Hadnot took over in February, this wing was something darker. Dubbed the Special Needs Unit, it’s where detention officers kept children in isolation for almost a week at a time while falsifying observation sheets and school attendance rosters, cultivating “systemic neglect” spanning years, according to 2024 findings by the Texas Juvenile Justice Department’s Office of Inspector General.

Open the door today, and a new mural installed by Hadnot’s team shows a child’s silhouette leaning against a tree, staring into a pastel blue sky painted across the walls. Yellow and black butterflies float under white letters: “Believe in yourself when no one else does.”

A regulation room separates youth and allows them to reset in the Henry Wade Juvenile Justice Center on Monday, Oct. 27, 2025, in Dallas. The walls were recently painted with various motivational murals.

Christine Vo / Staff Photographer

Breaking News

Soon there will be bean bag chairs, music, maybe calming aromatics – a place where children overwhelmed with the reality of their incarceration can come to recenter their emotions.

“You can still promote safety and security without it looking so harshly institutionalized,” Hadnot said. “At the end of the day, we’re dealing with children.”

By the time the nine-member Juvenile Board hired Hadnot in February, his predecessor had resigned, dozens of staff left or were fired and county officials said those failures confirmed by state investigators had been corrected.

The community was demanding deeper reform. Throughout his first nine months, Hadnot has ushered changes in staff culture and youth programming, and also launched incentive-based policies – all aimed at building public trust and a new approach to juvenile justice in Dallas County.

H. Lynn Hadnot, director of Dallas County Juvenile Services, (left) hugs motivational speaker Keidrain Brewster in the Henry Wade Juvenile Justice Center on Monday, Oct. 27, 2025, in Dallas. Brewster came to speak to the youth as a mentor.

Christine Vo / Staff Photographer

While Hadnot said reforms are still underway, community leaders who raised the alarm about conditions last year said the new administration has been transformative.

“During our protest I made the statement, and I stand by it, that dogs in Dallas County were treated better than our young people,” said Michael W. Waters, pastor of Abundant Life African Methodist Episcopal Church. “I will say I’ve been very encouraged by the progress that has been made within a very short expanse of time.”

***

Before Hadnot took over, problems in the detention center spanned multiple administrations.

The juvenile department is more than just the detention center, which now houses roughly 90 children. With a department budget of $80 million, 800 employees and nearly 3,200 kids referred to the system this year, the department operates multiple programs in Dallas County. But it was as if children in detention were not “seen and treated as human beings,” Waters said.

Teens wait in line for food during the fall festival at the Henry Wade Juvenile Justice Center in Dallas on Saturday, Nov. 1, 2025.

Juan Figueroa / Staff Photographer

The state’s yearlong investigation released in late 2024 concluded excessive seclusion in the Special Needs Unit began before former director Darryl Beatty was appointed in 2018.

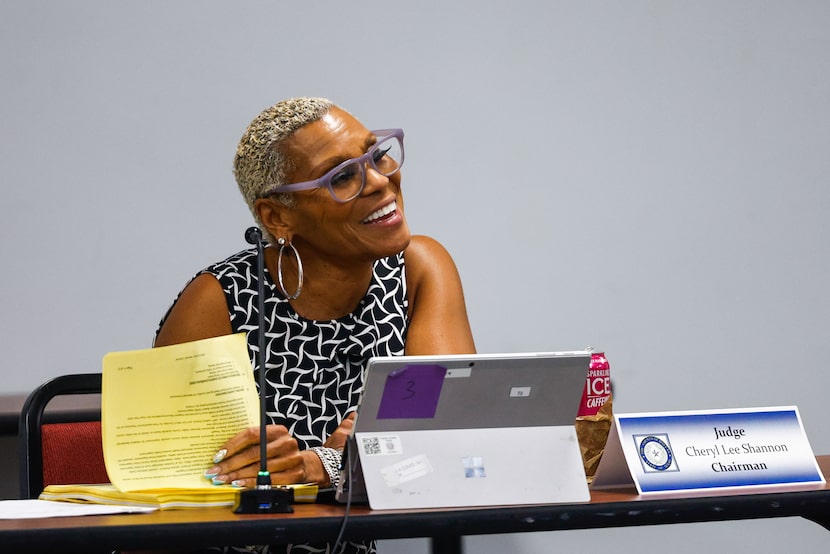

Beatty resigned in July 2024 amid the probe and did not respond to a phone call or text message for comment. Judge Cheryl Lee Shannon, the longtime chair of the Juvenile Board overseeing the department, also did not respond to a phone call or email for this story.

District Judge Cheryl Lee Shannon, who chairs the Juvenile Board, leads a board meeting in the Henry Wade Juvenile Justice Center on Monday, Oct. 27, 2025, in Dallas.

Christine Vo / Staff Photographer

After the board appointed Michael Griffiths, a veteran corrections official to serve as interim director upon Beatty’s exit, he said violations identified by the state were corrected. But it began the search for long-term change.

Hadnot said he felt a calling when Griffiths asked him to apply. He spent most of his career in Collin County’s Juvenile Probation Department, climbing from probation officer to director over 20 years, and becoming a statewide leader as chair of the Texas Juvenile Justice Advisory Council.

“Doing right by kids is something that’s very personal to me,” Hadnot said. “I believe this is literally what I was put on this planet for.”

His administration began with changing the punitive discipline focus to evidence-based incentive policies such as allowing juveniles to earn rewards for good behavior.

Teens shoot the basketball during the fall festival at the Henry Wade Juvenile Justice Center in Dallas on Saturday, Nov. 1, 2025.

Juan Figueroa / Staff Photographer

Now kids can earn tickets to purchase Pringles, Swiss Rolls and other treats in a “store” set up in a locker in the detention center. Staff is raising money for a game room with televisions and video games reserved for kids who buy access with good behavior.

“The punishment is already being in this building,” said Michael King, who was recruited by Hadnot as superintendent of pre-adjudication programs. “If we offer programming, normalcy, we’re going to much better prepare that kid to go back into the community a better version of themselves than if we just punish, punish, punish, punish.”

State standards allow kids to be secluded up to 48 hours at a time, but Hadnot only allows it for up to eight hours and for cases where safety is a concern.

In every instance of seclusion, which occurs in dorm rooms, the child receives mental health check-ins by clinical staff, pairing a therapeutic response to the discipline.

The administration adopted electronic badge systems for officers to make required check-ins on youth in their rooms, replacing the handwritten sheets falsified by previous staff. The technology switch was in motion before Hadnot’s February arrival, but County Commissioner Andrew Sommerman said the implementation overlapped with the transparency Hadnot is championing.

“You walk through where the parents meet their kids and the parents know (Hadnot’s) name; they have his personal phone information,” Sommerman said, noting he had not seen that under the last administration.

On a recent Saturday, kids earned the privilege to attend a fall festival in the gymnasium where a juvenile recreation coordinator was doubling that day as a DJ.

Teens play musical chairs during the fall festival at the Henry Wade Juvenile Justice Center in Dallas on Saturday, Nov. 1, 2025.

Juan Figueroa / Staff Photographer

They played musical chairs as balloons floated around them and sat together to dine on hot dogs, chips, punch and Twinkies.

“This is trying to give them something to look forward to,” King said. “It’s normalcy.”

Reform meant changing the way staff reported to work and interacted with kids, too. Early this year about 50% of positions were vacant following the exodus amid the state investigation. Others regularly called out sick, leaving a strained staff deeply disconnected to the kids, said detention officer Demond Porter.

(From left) Nurse Brandi Diggles and JSO Jazmin Montanez smile as they serve food during the fall festival at the Henry Wade Juvenile Justice Center in Dallas on Saturday, Nov. 1, 2025.

Juan Figueroa / Staff Photographer

Hadnot implemented a 12-hour shift schedule to give officers three or four days off in a row to recharge from demanding work. Eighty call-outs a month plummeted to single digits. Staffing levels reached 85%.

To meet his vision, Hadnot recruited new leadership. Five new administrators are people he’s worked with over the past 20 years, while he promoted other longtime officials he said have clear dedication to children.

“It’s an opportunity to do so much good,” said Ryan Bristow, deputy director of executive and administrative services, who left the Texas Juvenile Justice Department for the role this year.

(From left) Ryan Bristow, Deputy Director of Executive & Administrative Services, and superintendent of detention Mike King chat during the fall festival at the Henry Wade Juvenile Justice Center in Dallas on Saturday, Nov. 1, 2025.

Juan Figueroa / Staff Photographer

Staff are expected to be constantly on the floor, interacting with kids between classes, meals, recreation time — a shift from what Porter remembered under the last administration where he began as a detention officer in 2023.

“I was fresh out of college,” Porter said, “and I thought this is how it’s supposed to be – kids behind a door. That was wrong.”

Hadnot’s team also addressed glaring blind spots. To his surprise, classrooms didn’t have security cameras, so they installed them. Other cameras in the detention facility lacked sound, which he fixed.

Between February and October, violent incidents dropped by 90%, according to Hadnot.

Teens eat hot dogs during the fall festival at the Henry Wade Juvenile Justice Center in Dallas on Saturday, Nov. 1, 2025.

Juan Figueroa / Staff Photographer

***

On a Monday in October, staff hauled nine chairs to the middle of a dormitory. The boys took their seats, and Keidran Brewster began explaining he was once in their shoes – in generational trauma many children endure before their time in the system.

Brewster detailed his years in and out of juvenile detention as a child and jail as an adult. He talked about the glorification of gangs he deeply regrets and the death of his 16-year-old brother from gun violence.

“I’d give anything to be able to go back and tell my brother what I’m telling y’all,” Brewster said. “Why show my little brother how to gangbang when I can show him how to open up a successful company? It’s so many opportunities you have but you’re not giving yourself a fair chance.”

Motivational speaker Keidrain Brewster shares his story with the youth in the Henry Wade Juvenile Justice Center on Monday, Oct. 27, 2025, in Dallas. Brewster spent 13 years in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice.

Christine Vo / Staff Photographer

The visit was part of a “credible messenger” program Hadnot brought to detention where mentors and speakers deliver inspiration to kids who need to hear it the most — and to fill empty time that previously dotted kids’ days.

Elizabeth Henneke, CEO of the Lonestar Justice Alliance, a nonprofit that advocates for juvenile justice reforms, said the new incentives do not mean soft peddling detention.

In 2024, her alliance heard from parents of kids in the system about the prior administration restricting family visitation as a punitive measure, using excessive isolation and ignoring filthy conditions.

She said the shift to incentive-based policies is a best practice rooted in years of research. Books were previously not allowed in dorms for fear kids would throw them. Now books in rooms are a privilege that can be lost – because, Hadnot asked, isn’t that what you’d want for your own child?

“What we know is that young peoples’ brains are so much more motivated by incentives than they are by changing their behavior by punishment,” Henneke said. “What director Hadnot is really doing is making sure that stark, alarming detention is paired with the types of incentives that change behavior permanently so those young people don’t have to come back to the system.”

H. Lynn Hadnot, director of Dallas County Juvenile Services, stands in the Henry Wade Juvenile Justice Center on Monday, Oct. 27, 2025, in Dallas. Hadnot started the position in February.

Christine Vo / Staff Photographer

It may be too early to see if data backs up the effectiveness of the changes. Recidivism – the rate kids return to the system on new offenses – must be monitored over years, Henneke said. But through work underway in the district attorney’s office since 2023, more kids are being referred to community-based programming in lieu of detention.

Still, Hadnot acknowledged there is more to be done.

In September, juvenile detention officer Stephen Puzio was arrested and fired after allegedly assaulting a 15-year-old and putting him in a headlock.

Hadnot declined to discuss the case citing the active investigation but said he is focused on mitigating risks, even when the human condition causes people to fail.

Henneke and Waters, the community activist and pastor, said families are urging the department to contract with a new food vendor to replace the current service that is nearly inedible. Hadnot said that is underway and he hopes to put a contract out to bid in the next few weeks.

Although Hadnot has removed partitions that previously separated families and children during visitation, the Lonestar Justice Alliance is pushing for contact visits to allow hugging.

Hadnot said he wants that too but is configuring staffing and security measures.

“We think it’s been a transformative change for Dallas County,” Waters said, “and a marked step toward putting youth at the center.”