Bodily waste and other stuff that gets flushed down the toilet is no secret. In fact, it’s become public information.

Under a new pilot program, human excrement is being tested, recorded and studied in five Pikes Peak-region cities for the presence of opioids, including fentanyl, heroin and xylazine, a veterinary tranquilizer.

Why? Ultimately to provide early warnings to prevent spikes in overdoses and potentially save lives, according to leaders of the Pikes Peak Region 16 Opioid Abatement Council.

“The purpose is to determine both geographic and quantity patterns of the types of illicit drugs within wastewater to determine the scope and scale of the opioid challenge we’re facing as a region,” said Teller County Commissioner Erik Stone, the council’s vice chair.

The abatement council controls local government disbursement of money from numerous lawsuit settlements reached nationwide with Big Pharma companies, distributors and retail pharmacies, to resolve legal claims by state and local governments that the businesses contributed to the opioid epidemic.

Colorado is expected to receive up to $870 million in opioid settlement funds over 18 years, with 60% going to 19 regional abatement councils. The funds are required to be used for opioid abatement through prevention, treatment and harm-reduction strategies.

Wastewater treatment plants in north and south Colorado Springs and the towns of Fountain in El Paso County, and Woodland Park and Cripple Creek in Teller County, are participating in the one-year trial to collect samples and send them off for testing to C.E.C. Innovations in Calgary, Canada.

The cost is about $30,000 per location — or about $150,000 for all five sites — for the year, Stone said.

The state’s opioid overdose death rates have declined in recent years, particularly fentanyl-related fatalities, though they remain elevated compared with pre-pandemic levels.

Lynette Crow-Iverson, president of the Colorado Springs City Council and chair of the Region 16 Opioid Abatement Council, said she views the monitoring as an important step forward in addressing the problem.

“It allows us to understand what types of drugs are actually present in different parts of our community, rather than relying on assumptions or incomplete data,” she said.

Both Stone and Crow-Iverson said they’re interested in digging deeper, to tailor the testing to specific metro and rural areas of their communities — such as around schools, Stone said, or near the Springs Rescue Mission, Colorado Springs’ largest homeless shelter, Iverson-Crow said.

“So we can identify which substances are most prevalent where,” Iverson-Crow said. “Having this level of localized data can help us better target resources, prevention strategies and treatment options.”

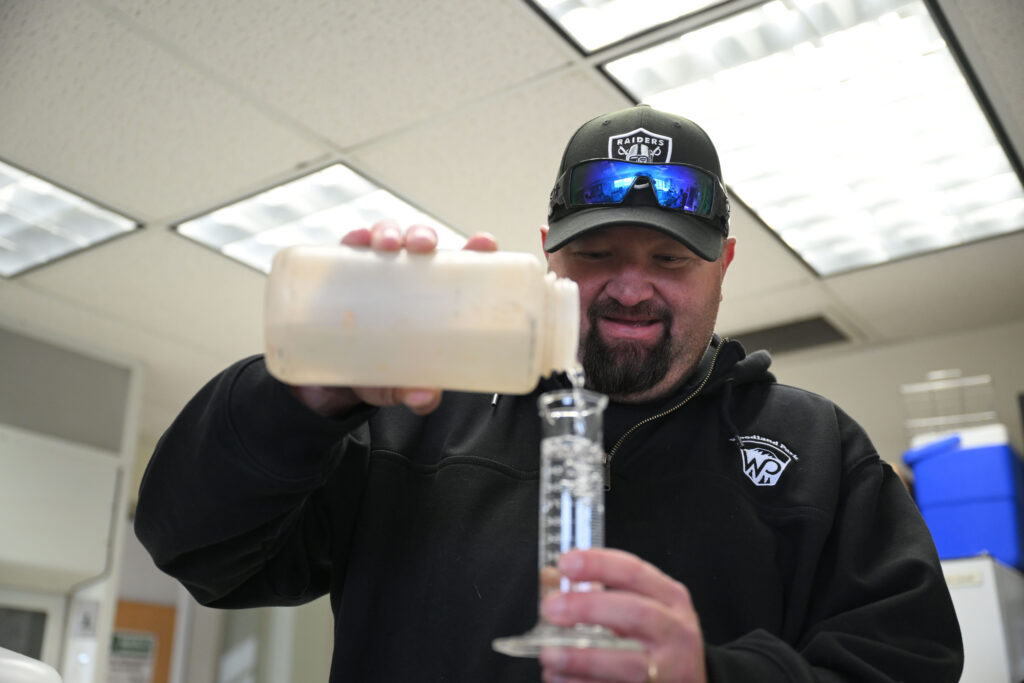

Jason Dukek, wastewater crew chief at the Woodland Park Wastewater Treatment plant, demonstrates collection and testing procedures for a new monitoring program testing for opioids on Wednesday, Dec. 10, 2025. (Stephen Swofford, The Gazette)

Jason Dukek, wastewater crew chief at the Woodland Park Wastewater Treatment plant, demonstrates collection and testing procedures for a new monitoring program testing for opioids on Wednesday, Dec. 10, 2025. (Stephen Swofford, The Gazette)

Technology to determine what’s ending up in municipal sewer systems has been around for a while, said Jason Dukek, wastewater crew chief for the city of Woodland Park.

A decade or more ago, he said, staff at a wastewater substation he worked at in Nevada spotted discards from heroin manufacturing, packaging or smoking. People were flushing foil balls, which upsets the biological treatment system. Testing traced the problem to a trailer park, Dukek said, and notices were posted on doors about the illegal drug’s presence in the area.

“We said we know what’s going on, please stop flushing it, and all of a sudden it just stopped,” Dukek said.

Wastewater monitoring gained national attention during the COVID-19 pandemic, when many communities enacted effluent tracking to predict outbreaks of the contagious and sometime fatal virus. Presence of the illness appeared in sewage days before people showed symptoms, so the methodology became a public health tool.

Local testing for opioid compounds began in October, after the regional council approved the contract with C.E.C.

Testing in Woodland Park started at twice a week and is decreasing to once a week, on Mondays, Dukek said, to capture weekend partying activity.

Participating facilities are provided with sample equipment and shipping.

In reviewing results from Woodland Park households, one sample of 25 milliliters contained nearly 800 chemicals, according to Dukek.

Along with substances from hair and beauty products and food, testing has uncovered “a broad mix of opioids, benzodiazepines, stimulants and psychoactive compounds,” the report said.

Since the start of the program two months ago, findings revealed nine unique opioid compounds, including fentanyl, and seven different mixtures of benzodiazepine, which are depressant drugs also called benzos.

For now, the process is setting baselines, but as it advances, “We could grab a sample and narrow it down to different parts of town and tell where use is coming from,” Dukek said.

To avoid legal issues, the process does not identify individuals but rather areas of concentration of the presence of drugs.

There’s no other “hard data” like what’s provided by examining wastewater, Stone said.

“We have a lot of anecdotal data, and we have coroner’s office deaths from overdoses and police arrests and seizures of illicit drugs, but there are variables in the human element of those,” he said.

Urine and feces present a more solid indication of the scope of prevalence.

An opioid abatement council in Denver is also studying wastewater for drugs.

Crow-Iverson hopes the initiative will present a clearer picture of the challenges of opioid use and “allow us to respond in ways that are more precise and effective, to use these funds in the best and highest way when responding to the opioid crisis in our communities.”

The Pikes Peak council also reviews applications for funding from local organizations and agencies for programs in youth prevention; community prevention, education and awareness; medication-assisted treatment and medications for opioid use disorder; recovery supports and transitions; and family advocacy.

In the past three years, it’s allocated nearly $10 million to such programs, according to distribution data.

Jason Dukek, wastewater crew chief for the city of Woodland Park, shows how he pulls a sample for testing for the presence of opioids on Wednesday, Dec. 10, 2025. (Stephen Swofford, The Gazette)

Jason Dukek, wastewater crew chief for the city of Woodland Park, shows how he pulls a sample for testing for the presence of opioids on Wednesday, Dec. 10, 2025. (Stephen Swofford, The Gazette)