Joe Ely, the West Texas troubadour who also played a pivotal role in turning Austin into a live music capital, died Monday. He was 78.

Ely died at his home in Taos, New Mexico, from complications of Lewy body dementia, a progressive brain disorder, as well as Parkinson’s disease and pneumonia, according to his publicist, Lance Cowan.

With his mournful voice and rock ‘n’ roll sensibility, Ely created an eclectic blend of honky-tonk, rockabilly, Tex-Mex, folk and blues that delighted fans and critics, but confused radio programmers.

As a songwriter, Ely spun Cormac McCarthy-style fever dreams like “Letter to Laredo” and “Me and Billy The Kid.” He was a master song interpreter as well, helping to popularize tunes by his West Texas colleagues Butch Hancock and Jimmie Dale Gilmore, among others. Ely recorded the definitive version of Robert Earl Keen’s much-covered “The Road Goes On Forever.”

News Roundups

Born in 1947 in Amarillo, the singer grew up in Lubbock, where he played in teen bands. His father died when he was 13, and three years later, Ely dropped out of high school and traveled the world, playing music and picking up odd jobs as a circus hand and fruit picker.

Back in Lubbock, he teamed up with Hancock and Gilmore to form the Flatlanders, who recorded one little-heard album in 1972 before disbanding for more than two decades.

“It didn’t last long,” Ely told The Dallas Morning News in 1995. “It was almost like those little dust devils that form on a hot day. We came together for about a year, spun around, did a record, and then spun off.”

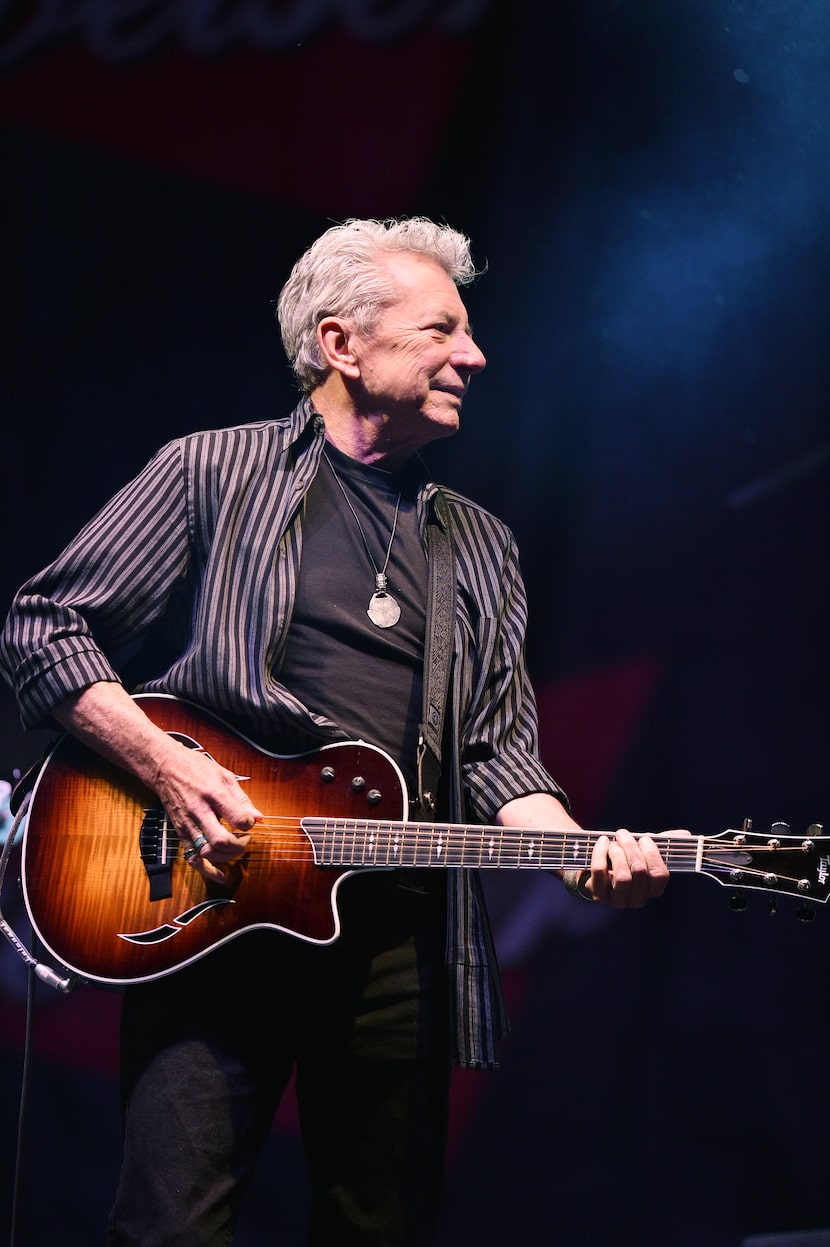

Joe Ely of The Flatlanders on the Jazz Stage during Saturday at the 2016 Denton Arts and Jazz Festival, Saturday, April 30, 2016, at Quakertown Park in Denton, Texas.

David Minton / DRC

Ely formed his own band, featuring steel guitarist Lloyd Maines, and scored a contract with MCA, which issued a series of acclaimed but poor-selling albums starting in 1977. He toured the U.S. relentlessly, earning the nickname “Lord of the Highway,” and Merle Haggard took him on tour in England, where the Clash fell in love with him.

The London punk band hired him as their opening act and asked him to sing backup, in Spanish, on their 1981 hit “Should I Stay or Should I Go.” Ely was thrilled, but as he told me in a 2002 interview, he always felt bad about the song’s mangled Spanish lyrics.

He moved to a ranch near Austin in the early ‘80s and became a staple of the city’s fast-growing music scene. Ely cemented his close relationship with the city by recording three live albums there, at Liberty Lunch, Antone’s and the Cactus Café.

MCA dropped him in the mid ’80s due to lackluster sales, but signed him again in 1990. On 1995’s Letter to Laredo, Ely was joined on two songs by Bruce Springsteen, a long-overdue pairing: the two had often been compared for their bittersweet storytelling and high-intensity live shows.

“It’s a little insane. People don’t know he’s introverted. All his energy comes out onstage,” Ely’s wife Sharon said, describing her husband’s concerts to The News in 1995. The singer performed in North Texas dozens of times, most often at Billy Bob’s Texas, Poor David’s Pub, Caravan of Dreams, the Granada Theater and the Kessler Theater.

In 1999, he earned his only Grammy for his work with Los Super Seven, a supergroup featuring fellow Texans Freddy Fender, Flaco Jiménez and Rick Trevino. Ely reteamed with the Flatlanders in the late ‘90s even as he continued to release solo albums, often on his own label.

Joe Ely performs on the first day of the Austin City Limits Music Festival on Sept. 17, 2004 in Austin.

ERICH SCHLEGEL

On Panhandle Rambler, released in 2015, the singer harkened back to his early days making music in Lubbock. The fierce wind in West Texas was a key ingredient in his career, he once told The News.

“It blows all the time,” he said. “So there’s this static electricity in the air and it makes you a little restless, it makes you want to move, to create something out of nothing.”

In 2007, he released a book, Bonfire of Roadmaps. And in 2020, during the pandemic, he recorded Love in the Midst of Mayhem, an album of songs he’d started working on years earlier. Before the album’s release, Ely described experiencing cognitive issues.

“I keep having this weird thing where I wake up and I don’t know where I am. I feel like I’m in a different city, at a different time in my life,” the singer told me at the time. “I thought, ‘I need to do something to keep me from going completely batty.’”

Ely cut back his touring schedule in recent years, and in September, he announced that he’d been diagnosed with Lewy body dementia and Parkinson’s disease. His survivors include his wife Sharon, whom he married in 1983, and their daughter Maria Elena, named after Buddy Holly’s widow, María Elena Holly.

Wrap it up: What Dallas music heads had on repeat in 2025

Wrap it up: What Dallas music heads had on repeat in 2025

Dallas DJ’s, artists and music leaders share the songs, albums and moments that defined their year.

Abraham Quintanilla Jr., father of Selena, has died

Abraham Quintanilla Jr., father of Selena, has died

He was 86.