The Astrodome is more than just a building. Today the landmark serves as a reminder that in the 1960s, one city had the nerve to change the way the world thought about sports, entertainment and architecture. Judge Roy Hofheinz’s dream transformed Houston into the city of the future. Today, however, the Eighth Wonder of the World sits empty, fenced off and waiting for a future that never was.

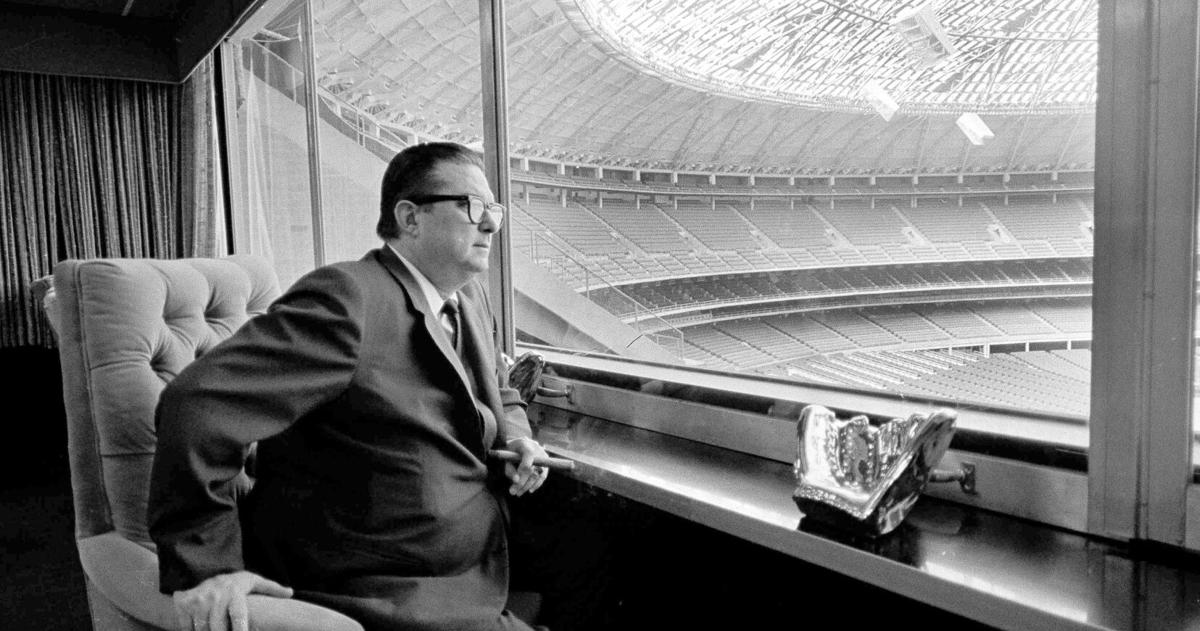

Roy Hofheinz, also known as “The Judge,” president of the Houston Astros Sports Association, owners of the Houston Astros, looks over the work that is being done on the Houston Domed Stadium from the private apartment box high in right field March 4, 1965.

ED KOLENOVSKY/The Associated Press

Ideas have been presented. Plans have been made, then scrapped. Millions of words have been written in numerous publications, mostly rehashing the same facts. But as the building turned 60 earlier this year, we raise one question: What would Judge Hofheinz want done with his baby?

The Judge passed away in 1982, so to get as close of an answer as possible, I spoke with a few people with close knowledge of him and the Dome whose collective voices paint a picture of who exactly Hofheinz was. The Judge generally wasn’t one to hold on to relics, but to dream big, chase and realize those dreams.

Roy Hofheinz, former mayor of Houston and Harris County judge, watches from his private box in the Astrodome as the Houston Astros defeat the Philadelphia Phillies 1-0 in a National League playoff game Oct. 10, 1980. Hofheinz helped spearhead the drive that led to the construction of the Astrodome in the early 1960s and was a former owner of the Astros ball club.

The Associated Press

Dinn Mann, the Judge’s grandson, spent summers with him until high school. He saw firsthand the energy and get-it-done attitude of a man who believed his beloved city could and should be a major player on the world stage.

“I find it interesting how many people try to speak for him who never met him,” Mann said. “I not only knew him, but I lived with him. My grandfather was not a man who sat still, but wanted to keep moving forward always.”

Roy Mark Hofheinz was born in Beaumont in 1912 but grew up in a working-class family in Houston. After law school, he was elected state representative at age 22, Harris County judge at age 24, and later, Houston mayor. He integrated the city’s buses, libraries and restrooms.

Legend has it, Hofheinz was traveling home with his daughter Dene (Mann’s mother) after the minor league Houston Buffaloes had a game rained out. Dene, the story goes, asked why they couldn’t just play baseball inside. Additionally, a domed stadium in Brooklyn was proposed in the early 1950s by Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley but was nixed by New York City construction coordinator Robert Moses. Hofheinz and his wife also visited the Colosseum in Rome, where they learned about ancient slaves pulling a shade over the spectators. So the building blocks were in place, but the dream of an indoor sports palace had never been successfully realized.

Hofheinz loved Houston, period. He believed it to be the world’s greatest city and that it needed something to make it known worldwide. An air-conditioned cathedral of entertainment to combat Texas’ summer heat and humidity was just the answer.

“The Judge didn’t build it just to have a stadium,” said Mike Acosta, the longtime Astros’ team historian who now works with the Astrodome Conservancy. “He wanted to show the world what Houston was capable of. Everything about it was about civic pride. It was bigger than sports.”

Hofheinz campaigned for the bond election to build the Astroome all over Harris County, but especially in predominantly African-American areas. The Dome was to be non-segregated upon its opening, a monumental leap forward for the South’s biggest city.

The Houston Sports Association, comprising Texaco heir Craig Cullinen, sportswriter George Kirksey, financier R.E. “Bob” Smith and Hofheinz, was awarded an expansion franchise by the National League in 1962, but there was just one problem: The domed stadium wouldn’t be ready until 1965. The club considered playing at the old minor league ballpark, Buffalo Stadium, until the Dome was completed, but Hofheinz would have none of it. So a temporary 33,000-seat park was constructed in what would become the Dome’s parking lot.

Colt Stadium was the only major league ballpark where bug spray outsold beer. Thanks to Houston’s famous mosquito infestation and a lack of cover over the grandstand, it was not a pleasant place to watch a game. Both of this author’s grandfathers are lifelong baseball fans who attended games at Colt Stadium, and they still to this day recount stories about the park’s shortcomings. But by placing the oversized Little League park in the shadow of the under-construction Astrodome, fans could watch as construction progressed next door and dream of its luxury.

And it lived up to the hype. The difference was night-and-day. Upon its 1965 opening, it was compared to everything from the Pantheon to the Palace of Versailles. The two grandfathers mentioned above attended the first game against the New York Yankees.

The newly rebranded Astros beat the New York Yankees in the Dome’s first exhibition game on April 9, 1965. Both aforementioned grandfathers were in attendance to see their hero Mickey Mantle hit the stadium’s first home run. [EDITOR’S NOTE: Fear not. They are not Yankee fans today.]

Bob Hope mused, “If it had a maternity ward and a cemetery, you’d never have to leave.” It truly was a place of luxury, featuring padded seats, air conditioning, skybox suites and the world’s first animated scoreboard.

Football, basketball, tennis, rodeo, concerts, church services — you name it, the Dome hosted it.

For “Judge” Roy Hofheinz, the Houston Astrodome operator and 88% owner pictured in his apartment in the right field in the four-level VIP area of the stadium Jan. 9, 1968, spectacular dealings are becoming a way of life. Here, he sits in one of the three circus rooms he has built for entertainment within the Astrodome, surrounded by symbols of the circus.

ED KOLENOVSKY/The Associated Press

Bill Brown, who was the Astros’ play-by-play broadcaster for decades, still recalls the sense of awe he felt the first time he visited the Dome.

“It was so futuristic, and it put Houston decades ahead of everyone else,” Brown said. “I loved it. You had no rain delays, you had plenty of space, and you had predictability. But more than that, it sent the message that Houston is a world-class city.”

Most sports fans know the story: Outfielders complained about the roof’s glare, so the Plexiglass was painted over, which in turn killed the natural grass playing surface. So the Astrodome was the first major stadium to use artificial turf, which was then appropriately named AstroTurf. The thin plastic carpet over a concrete slab made for a fast but consistent surface for defenders to play.

Terry Puhl spent 14 of his 15 major league seasons roaming the outfield for the Astros. As a young man from Melville, Saskatchewan, playing in the Dome was both a dream and a challenge.

“It was such a beautiful building,” Puhl said. “I remember walking in the first time, thinking you could put the entire town of Melville inside and it wouldn’t even dent the place.

Thanks to the bright roof, for day games outfielders had to watch balls right off the bat to have a shot at making a play. It was also a tremendous pitcher’s park, as thanks to the air conditioning, the ball did not carry well. All that gave the Astros an advantage.

“Once you learned to play it, it was great,” Puhl said. “I still remember catching fly balls from Mike Schmidt on the warning track, and he would slam his helmet down in frustration. But that place changed my life. My wife and I moved to Houston and became Americans. The Dome was part of that story.”

By the 1990s, the Astrodome’s star had waned. After demanding additional seats and the iconic scoreboard’s removal, the Houston Oilers moved to Tennessee in 1997. Those outfield seats thus made the place less suitable for baseball, so the Astros moved to the new downtown ballpark in 2000. It continued to host other events, including the Lufkin Panthers’ 2001 state football championship, the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo through its 2002 edition, and housed refugees from New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina. But by 2006 the fire marshal declared the Dome unfit for occupancy. Ever since, ideas for the Dome’s restoration and renovation have been thought up and bandied about, but none have been brought to fruition.

“Houston sat back for years while forces at play kept anything from moving forward,” Mann said. “That’s not how my grandfather operated. He believed in collaboration and consensus-building, but he also knew sometimes you have to lead and inspire confidence. It doesn’t just magically happen.”

“Hofheinz would be disappointed in the lack of leadership,” Acosta said. “Back in the ’60s, people in Houston were willing to take chances. They believed in creating things that didn’t exist. We’ve gotten complacent. Everyone points fingers, and the Dome just sits there.”

So if the Judge were here today, what would he say?

Judge Roy Hofheinz stands in front of the Astrodome in Houston April 19, 1968.

The Associated Press

All four men agree he would not want the Astrodome torn down. The place is more than just concrete and steel — it’s part of the city’s, nay, Texas’ DNA, now protected alongside the Alamo and State Capitol as an official state antiquities landmark.

But neither would Hofheinz want it frozen as a museum place.

“My grandfather wouldn’t hug it as a relic,” Mann said. “He would reimagine it. He’d want to make it relevant again.”

That means thinking big yet again. Mann says it should be the centerpiece of a modernized NRG Park.

“Think of Disney World,” Mann said. “There’s a castle in the middle, and everything else is built around it. The Astrodome could be the castle. Renovate it and make it state-of-the-art as the anchor of a mixed-use development. Make Houston globally relevant again.”

“Event space, hotel, retail, museum, even indoor parking — those are all possibilities,” Brown said. “It will take imagination and it will take the Texans and the Rodeo getting on board.”

The trouble, as with anything else, is a game of politics. The Houston Texans and the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo hold the power in making things happen at NRG Park. Neither organization has, at least publicly, shown much appetite for a Dome renovation unless it directly benefits them. Currently, both are focused on renovating NRG Stadium or even building yet another new stadium. Harris County leadership has also wavered, not committing resources to a project that could cost hundreds of millions of dollars.

But the Judge, his grandson insists, would have been undeterred. Mann recalled pushing his wheelchair-bound grandfather on one particular occasion near the end of his life.

“My grandfather told me, ‘There’s a difference between motion and progress,’” Mann said. “That quote has stuck with me all these years, and I think it’s pretty apropos when talking about the Astrodome.”

The key, as Acosta argues, is to treat the Dome as part of a larger vision, as opposed to a shell of its 60-year-old self.

“The Astrodome was Houston’s living room,” Acosta said. “The place was full when they welcomed home the Apollo 11 astronauts, when Billy Graham preached there, and when Elvis sang there. The sense of awe is still there, but we need leaders willing to make something happen.”

A view looking west of NRG Stadium, left, home to the Houston Texans, and the now dormant Astrodome, right, in the area now know as NRG Park Nov. 13, 2024, in Houston. The Astrodome Conservancy, a group dedicated to preserving the structure, has proposed a multi-use renovation for the legendary building.

MICHAEL WYKE/The Associated Press

One of Acosta’s favorite sayings is that a Houstonian is someone who has made the best of his or her opportunity. That definition, more than anything, frames the Dome’s story. In the 1960s, Houston made the best of its opportunity by building something that had never been done before. Today, the opportunity is different: restoring, reimagining, and reusing a legendary building that still has the power to inspire the world.

“What would justice to the Astrodome look like?” Acosta asked. “To me, it’s not tearing it down, and it’s not continuing to let it sit vacant. It should be used to create a place where families want to go again, where people want to visit, where Houstonians feel pride.”

Today, the Dome still sits. Most of the rainbow-colored seats have been removed. The AstroTurf playing surface is rolled up. But you can imagine Cesar Cedeno racing into the gap in left-center to catch a fly ball, or Earl Campbell slicing through a defense like a knife through butter. You can almost hear the Judge himself, chewing on his cigar, explaining why Houston, the greatest city in the world, deserved nothing less than the biggest, most impressive idea anyone had ever dreamed up.

For Houstonians still wondering what to do with the Eighth Wonder of the World, perhaps dreaming big is just the answer.

Roy Hofheinz of Houston, known as “The Judge,” sits in a zebra skin-covered chair in a four-level VIP area of the Houston Astrodome, within an oak-paneled conference room shown Jan. 9, 1968.

ED KOLENOVSKY/The Associated Press