Bernie Olivas was 10 years old when he first walked into Sun Bowl Stadium.

It was 1963 — the first year the annual bowl game was played in the stadium on the University of Texas at El Paso campus nestled into the foothills of the Franklin Mountains — and Olivas remembers it clearly. The University of Oregon played Southern Methodist University, and the experience left an impression that never faded.

“I fell in love,” Olivas said. “I have not missed a Sun Bowl since. I’m 72 years old, so that’s 62 Sun Bowls I’ve never missed.”

More than six decades later, Olivas has seen many versions of the Sun Bowl — first as a young fan growing up within walking distance of the stadium, then as a volunteer, and now as the executive director of the Sun Bowl Association, a role he has held since 2001.

In the years since, Olivas has overseen a game that has weathered conference realignment, shifts in television, economic downturns and a pandemic that forced the only cancellation in the Sun Bowl’s 90-year history. He has watched the stadium expand and contract, attendance fluctuate, and college football itself evolve into a sport increasingly shaped by postseason structure and media rights.

As the Tony the Tiger Sun Bowl prepares to host its 92nd edition this week — a matchup between Arizona State University and Duke University — the game enters another period of transition. The bowl is in its final contract year with both the Atlantic Coast Conference and the Pacific-12 Conference’s legacy teams. However, earlier this year, the Sun Bowl announced a renewed broadcast partnership with CBS, securing national television exposure through 2030. At a time when some bowl games have disappeared or moved off major networks, the agreement provides a measure of continuity.

“You know, the (College Football Playoff) kind of could have a little effect on it later on,” Olivas said. “But I think most of the bowls are gonna be pretty safe. So, I think we’re alright.”

That confidence is shared by leadership beyond El Paso.

From the perspective of Bowl Season — the organization representing the nation’s bowl games — the Sun Bowl’s longevity and continued visibility place it among the sport’s foundational postseason events.

Officials with the Sun Bowl Association announce the matchup for the 2024 Tony the Tiger Sun Bowl during the annual selection event at Sunland Park Racetrack and Casino. The December bowl game, one of the longest-running in college football, will be played at Sun Bowl Stadium in El Paso. (Courtesy Sun Bowl Association)

Officials with the Sun Bowl Association announce the matchup for the 2024 Tony the Tiger Sun Bowl during the annual selection event at Sunland Park Racetrack and Casino. The December bowl game, one of the longest-running in college football, will be played at Sun Bowl Stadium in El Paso. (Courtesy Sun Bowl Association)

“The Sun Bowl is the second-oldest bowl game, having started over 90 years ago,” said Nick Carparelli, executive director of Bowl Season. “For this reason, it holds a very special place in the history of college football.”

Carparelli said the modern postseason includes both the College Football Playoff and the broader bowl system, each serving a distinct role. The CFP is a postseason tournament that features the top NCAA Division I Football Bowl Subdivision teams to crown a national champion, which expanded from four to 12 teams starting in the 2024 season.

“Today, college football’s postseason is comprised of two equal components – the CFP and Bowl Season – both are extremely meaningful and important to the sport,” he said.

That framing matters for bowls such as the Sun Bowl, which operate outside the playoff but remain a consistent part of college football’s year-end calendar.

“College football needs postseason opportunities that serve the 130-plus FBS institutions who are all at different points in their development and evolution as football programs,” Carparelli said. “Every bowl game is meaningful to those programs and their fanbases who participate in them, regardless of their role in the national championship equation.”

For Olivas, those broader conversations exist alongside the immediate task of staging this year’s game.

“Pretty much, absolutely,” he said, when asked whether he thinks about the Sun Bowl approaching its 100th anniversary in 2035. “Day to day, that doesn’t drive me as much as it’s day to day to this year’s game. We’ve got something right here. Let’s get this one done before we can move to the next.”

The Sun Bowl will be played again this year as it has for most of the past nine decades. What shape college football’s postseason ultimately takes — and how bowl games fit within it — remains a question still being worked out elsewhere.

A broadcast deal — and a waiting period

The Sun Bowl’s most immediate point of certainty comes from television.

Earlier this year, the Sun Bowl Association announced a renewed broadcast partnership with CBS, extending the game’s presence on network television through 2030. The agreement keeps the Sun Bowl on one of college football’s primary broadcast platforms at a time when media rights and postseason windows are shifting across the sport.

From a national standpoint, Bowl Season leadership views that continuity as significant.

Sun Bowl Association officials, including executive director Bernie Olivas, center, communicate with other bowl organizations across the country during the selection process. The coordinated effort helps determine which teams are selected to play in the Tony the Tiger Sun Bowl in El Paso. (Courtesy Sun Bowl Association)

Sun Bowl Association officials, including executive director Bernie Olivas, center, communicate with other bowl organizations across the country during the selection process. The coordinated effort helps determine which teams are selected to play in the Tony the Tiger Sun Bowl in El Paso. (Courtesy Sun Bowl Association)

“College football bowl games provide great value to their television partners,” Carparelli said. “No other sports programming outside of the NFL attracts more viewers than bowl games. CBS’ long-standing commitment to the Sun Bowl is a testament to that.”

The deal ensures national exposure, but it does not answer every question facing bowls in the years ahead.

Many of those questions are tied to the future structure of the College Football Playoff. In November, the CFP and ESPN announced they would extend the deadline for finalizing the next phase of the playoff format, moving it from Dec. 1 into late January.

“While no change to the current format is definite, this extension will allow the Management Committee additional time to evaluate the second year of the expanded playoff and ensure any potential modifications are carefully considered, fully vetted, and in the best interests of student-athletes, schools and fans,” said Rich Clark, executive director of the CFP.

For bowl games, that timeline matters. Conference tie-ins, selection order and postseason planning often flow from playoff decisions. Until those decisions are finalized, bowls remain in a holding pattern.

“Everybody’s waiting on the CFP,” Olivas said.

For now, Olivas said, the Sun Bowl continues to operate with the understanding that clarity will come later.

Opt-outs and a changing postseason

The Sun Bowl’s place in the modern postseason has also been shaped by changes on the field — particularly the growing prevalence of player opt-outs.

The first high-profile instance came after the 2016 season, when Stanford University running back and current San Francisco 49er Christian McCaffrey opted not to play in the Sun Bowl as he prepared for the NFL draft.

At the time, such decisions were rare. In the years since, they have become increasingly common across bowl games, especially among players with professional aspirations.

Notre Dame quarterback Steve Angeli prepares to take a snap during the 2023 Tony the Tiger Sun Bowl against Oregon State at Sun Bowl Stadium in El Paso. Making his first career start after Sam Hartman’s opted out of the game, Angeli threw for 232 yards and three touchdowns to lead the Irish to a 40–8 victory. His performance elevated his standing within the program and later translated into expanded playing time, including an appearance in the Orange Bowl College Football Playoff semifinal against Penn State. (Courtesy Sun Bowl Association)

Notre Dame quarterback Steve Angeli prepares to take a snap during the 2023 Tony the Tiger Sun Bowl against Oregon State at Sun Bowl Stadium in El Paso. Making his first career start after Sam Hartman’s opted out of the game, Angeli threw for 232 yards and three touchdowns to lead the Irish to a 40–8 victory. His performance elevated his standing within the program and later translated into expanded playing time, including an appearance in the Orange Bowl College Football Playoff semifinal against Penn State. (Courtesy Sun Bowl Association)

By 2023, when University of Notre Dame quarterback Sam Hartman opted out of the Sun Bowl, the decision drew far less attention.

Olivas said the Sun Bowl has adjusted its expectations accordingly.

“You know, as far as opt-outs are concerned, we invite schools for the name on the front, not on the back,” he said. “That’s the way we see it.”

That approach, Olivas said, reflects the reality of today’s postseason, where rosters can look different from what fans saw during the regular season.

“Somebody will show up and he’ll play hard,” he said. “We’ve had some replacements that have been great, that have really come out.”

Those opportunities, he said, can serve as a platform for players stepping into larger roles.

When Hartman opted out in 2023, it cleared a path for backup quarterback Steve Angeli to showcase his talent. Angeli threw for 232 yards and three touchdowns en route to a 40-8 win over Oregon State University. At the end of the 2024-25 season, Angeli made an appearance in the Fighting Irish’s Capital One Orange Bowl CFP semifinal against Penn State.

Opt-outs are not the only roster disruptions bowls now face. Coaching turnover has increasingly affected postseason games, with staffs leaving for new positions before bowl season begins.

“That’s a whole other thing that impacts the game, too, is these coaches that end up leaving or get fired or what have you,” Olivas said.

Attendance and El Paso’s role

Even as college football’s postseason has changed, attendance at the Sun Bowl has remained relatively steady.

Since Olivas became executive director in 2001, the game has dipped below 40,000 fans only twice — once in 2017 and again in 2021, when the bowl was played amid the tail end of the COVID-19 pandemic. In most years, attendance has exceeded that mark, even as some bowls nationally have struggled to draw crowds.

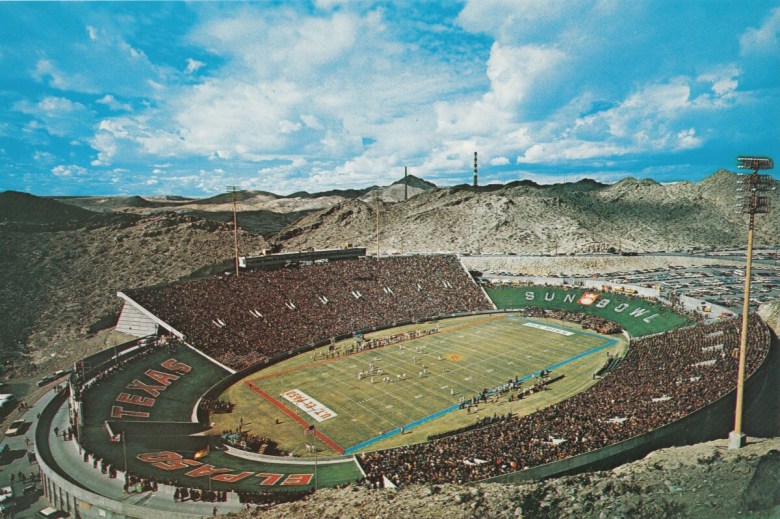

An aerial view of Sun Bowl Stadium during the 1967 Sun Bowl in El Paso. Ole Miss defeated UTEP 32–14 in the postseason matchup, which was color-televised nationally by CBS. The Sun Bowl is the nation’s second-oldest postseason college football game. (Courtesy El Paso Museum of History)

An aerial view of Sun Bowl Stadium during the 1967 Sun Bowl in El Paso. Ole Miss defeated UTEP 32–14 in the postseason matchup, which was color-televised nationally by CBS. The Sun Bowl is the nation’s second-oldest postseason college football game. (Courtesy El Paso Museum of History)

Olivas attributes that consistency to local support rather than to traveling fan bases.

“I still think the Sun Bowl has the largest economic impact of an annual event in El Paso,” Olivas said.

While the Sun Bowl is widely viewed as an economic plus for the region, some caution that the precise scale of its impact has never been formally measured.

Tom Fullerton, an economics and finance professor at the University of Texas at El Paso, said that despite the Sun Bowl’s long history, no comprehensive analysis of its economic impact has ever been conducted.

“Because so little data have been assembled related to the second-oldest bowl game in the NCAA, no econometric analysis of Sun Bowl economic impacts has ever been carried out,” Fullerton said. “That’s a surprising knowledge gap given the tremendous history of this game.”

From a tourism perspective, the timing of the game has long been significant. Brooke Underwood, executive director of Visit El Paso, said late December is typically a slower period for travel.

“Typically, this time of year is a softer period for tourism,” Underwood said. “So, having the Sun Bowl, with its longstanding, successful track record at the very end of the year, in what is typically a soft period, is fantastic.”

Visit El Paso’s visitation data shows the Sun Bowl functions primarily as a regional, drive-market event, with a majority of visitors coming from within a day’s drive, including Southern New Mexico and parts of Texas and Arizona. Underwood said that profile aligns with El Paso’s existing hospitality and tourism infrastructure.

“They bring bands, they bring cheer groups, and then, of course, alumni,” she said. “So, that is fantastic to fill our hotels in what typically might be seen as a softer period.”

Fullerton said Visit El Paso’s data aligns with broader trends in the region’s hospitality sector, which has seen sustained investment over the past decade.

“The lodging segment of the El Paso metropolitan economy is in very good shape and highly dynamic,” he said, noting that much of the recent investment has been in higher-end facilities — a reflection of national and regional economic growth rather than any single event.

Rather than relying on a single day of activity, the Sun Bowl extends across multiple days through team arrivals, fan events, parades and pregame activities Downtown and on the UTEP campus.

“It’s really Visit El Paso’s job to then build an itinerary around that major attraction,” Underwood said.

Tony the Tiger and the Amigo Man celebrate the 2019 Sun Bowl Fan Fiesta in Downtown El Paso. (Courtesy Sun Bowl Association)

Tony the Tiger and the Amigo Man celebrate the 2019 Sun Bowl Fan Fiesta in Downtown El Paso. (Courtesy Sun Bowl Association)

For Bowl Season, that kind of local integration is part of what has allowed certain bowls to remain stable.

“The bowl system is one of the best promotional vehicles the game of college football has,” Carparelli said. “Providing over 40 communities across the country the opportunity to experience the game and develop future fans of the sport.”

In El Paso, that opportunity has remained closely tied to the city’s willingness to support the game, regardless of matchup or roster changes — a factor Olivas said continues to matter as the postseason evolves.

“Our city is going to support us,” he said.

Conference ties — and what comes next

Beyond television and attendance, the Sun Bowl’s future also depends on conference relationships — agreements that remain unsettled as college football continues to adjust to realignment. The Sun Bowl’s deals with the Pacific-12 Conference’s legacy teams and the Atlantic Coast Conference expires at the conclusion of this season.

Olivas said the Sun Bowl’s contracts are with conferences, not individual schools, a distinction that has become more pronounced as leagues grow larger and the number of power conferences shrinks.

The Sun Bowl has historically hosted teams from major conferences, and Olivas said that remains the preference moving forward.

“We do want, obviously, we want to be with power schools,” he said. “So, we want to negotiate with power conferences, and there’s only four of them now.”

Which conferences those will be — and how bowl selections will work — is still tied to decisions being made at the College Football Playoff level.

From Bowl Season’s perspective, that uncertainty does not diminish the role bowls play within the sport.

“College football needs bowl games as much as it needs the CFP,” Carparelli said.

For now, the Sun Bowl game continues — much as it has since a 10-year-old boy first walked into Sun Bowl Stadium and decided he would keep coming back.

Make plans

What: 92nd annual Tony the Tiger Sun Bowl

Matchup: Arizona State Sun Devils (8-4) vs. Duke Blue Devils (8-5, 2025 Atlantic Coast Conference champions)

When: Kickoff, noon Wednesday, Dec. 31. Gates open at 9:30 a.m.

Where: Sun Bowl Stadium, 2701 Sun Bowl Drive, on the University of Texas at El Paso campus

How much: Tickets start at $31 via Ticketmaster at sunbowl.org/tickets. Game-day tickets available at north and south entrances of Sun Bowl Stadium.

Related

LISTEN: EL PASO MATTERS PODCAST