Most people understand that trash needs to go somewhere, but a rapidly growing North Texas faces increasing challenges on where to put the waste that comes from more residents, businesses and construction.

This is part of the Report’s special 1 Million & Counting growth series, which will be published on Mondays into October. The reporting will lead to a growth summit Oct. 23 at the downtown Tarrant County College Trinity River Campus.

Take a recent plan to build a landfill in Lake Worth to process Tarrant County-area waste from construction and demolition projects, much of that stemming from booming growth. Residents near the Silver Creek neighborhood and elected officials opposed the project, saying they worried how local water sources, such as the nearby lake, would be impacted by runoff from the trash.

The developer ultimately withdrew its application, but residents and others say that the northwest area of Tarrant County is still being eyed by industrial developers. Their concerns are part of a larger ask by the community that new developments — from housing to landfills — be approached with minimal impact on the environment, housing and transportation.

“It’s going to get more crowded, and it’s coming,” Silver Creek resident Don Brewer said. “Change is coming.”

Population increases and growing development in and around Tarrant County are adding strain to waste management and landfill capacity — including at Fort Worth’s only dump site, which is expected to max out in about a decade, almost 30 years sooner than expected.

This year, Fort Worth reached 1 million residents. Estimates show Tarrant County will reach 2.8 million residents by 2040.

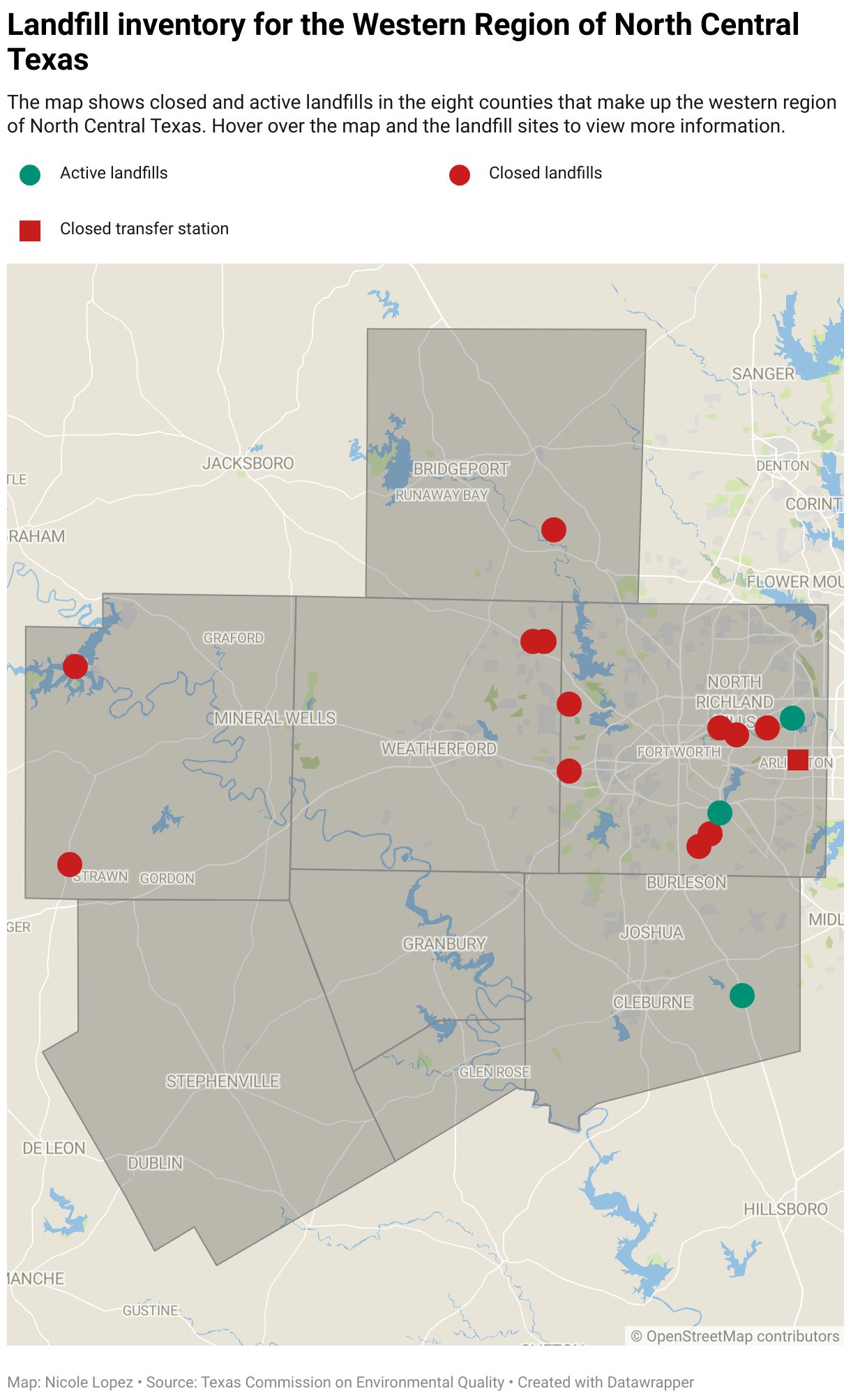

By then, waste planners project, residents in the area are on track to generate about 70 million tons of trash. The planners examined patterns for the western side of North Texas, which includes eight counties, to predict waste and capacity over a two-decade period starting in 2022.

Those predictions put the area’s three landfills beyond their capacity of 63 million tons.

Meanwhile, planning for landfills takes time as it requires securing sites, navigating millions in costs to obtain an environmental permit and working with nearby residents. That process can take up to 20 years, waste industry officials say.

Jim Lattimore’s company has subcontracted with the city for over two decades to oversee the Fort Worth dump site, which is along the southeastern part of the city near Kennedale.

Fort Worth city officials and contractors do “everything they can” to maximize its capacity, including compacting loose trash, Lattimore said. But population growth is one of the leading causes of landfills nearing closure.

“I don’t see any efforts right now toward permitting new capacity, and I think that’s something that needs some attention,” Lattimore said.

Area leaders know more landfills will be needed as well as other solutions to deal with waste.

Left: Mounds created by trash are incorporated into the roadways of the landfill. Right: The Fort Worth skyline is visible from the southeast landfill on Oct. 2, 2025. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

Left: Mounds created by trash are incorporated into the roadways of the landfill. Right: The Fort Worth skyline is visible from the southeast landfill on Oct. 2, 2025. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

This prompts local officials to be environmentally minded as developers with waste needs move into the area, said Tarrant County Commissioner Manny Ramirez who was at the forefront fighting the Lake Worth proposal.

“It’s only fair for developers, communities, government officials alike, to all have a solid idea and plan on where we see the development of our landfills, waste management facilities,” Ramirez said. “There has to be a clear road map.”

Growth gradually increases Fort Worth’s waste stream

Rapidly rising population estimates prompted the North Central Texas Council of Governments to seek ways to more efficiently process waste and minimize landfilling.

“People are not going to stop creating trash, right? So it has to go somewhere,” said Hannah Ordonez, a senior waste planner with the council.

In 2022, the council outlined recommendations for North Texas that included offering business incentives for using recyclable materials and for manufacturers that reduce excess packaging and single-use products.

But the strategies listed in the solid waste plan also require effort from local leaders to meet growing demands. For example, area city and county officials should work to expand landfills, minimize illegal dumping and encourage environmental stewardship, according to recommendations in the plan.

Other efforts could include attracting compost businesses and investing in recycling- and organic waste processing-focused positions at the city.

Which counties use the Western Region’s municipal solid waste landfills?

Tarrant County

Parker County

Johnson County

Erath County

Hood County

Somervell County

Wise County

Palo Pinto County

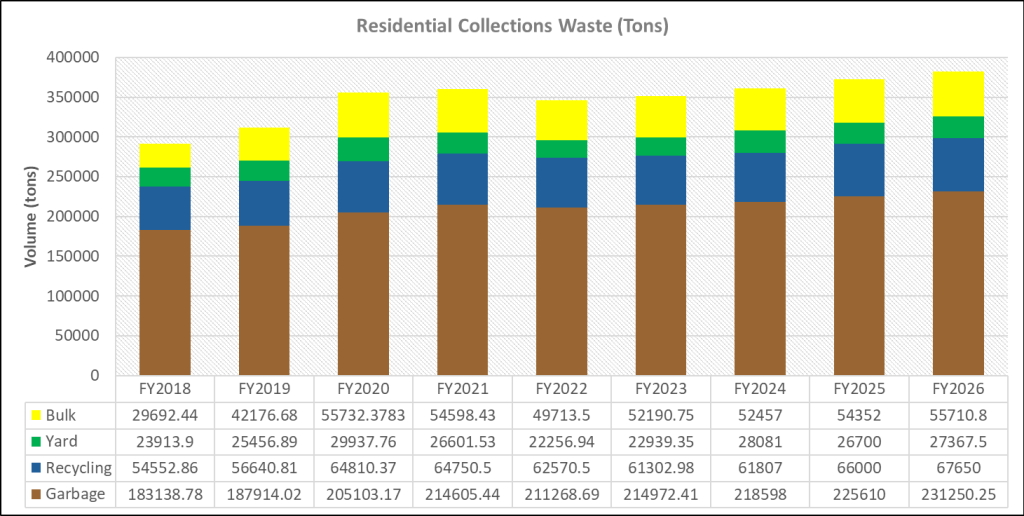

Fort Worth collected about 374,000 tons of waste so far this year, accounting for bulk, yard, recycling and residential garbage. That’s above the average amount of 350,000 tons of trash generated for each of the last three years.

Fort Worth leaders could offset a premature closure of its only landfill, originally slated to last through the 2060s, by identifying new dump sites and putting more public dollars into modern technology, Lattimore said.

City staffers are working on long-term solid waste solutions, environmental services department director Cody Whittenburg said in a statement. Those plans recommend officials consider waste transfer stations, new landfills and additional recycling centers.

“We know the (landfill) is going to fill up and reach its capacity. We have to start planning for the future,” Whittenburg later told council members during an Oct. 14 update.

The other two landfills that serve the Tarrant County area are in north Arlington and Alvarado.

Arlington’s dump site, which has been in operation since the 1960s, could be used for another 30 years or longer following an expansion project approved in 2014. The Turkey Creek site in Alvarado is expected to max out in two years, the latest data shows.

The graph shows the amount of different types of residential waste collected in Fort Worth’s service area between 2018 and 2025. The graph includes Fort Worth’s waste projections for 2026. (Courtesy image | City of Fort Worth)

The graph shows the amount of different types of residential waste collected in Fort Worth’s service area between 2018 and 2025. The graph includes Fort Worth’s waste projections for 2026. (Courtesy image | City of Fort Worth)

While Fort Worth can use those sites, that would cause transportation costs to surge, officials said.

Fort Worth solid waste staffers meet daily with the trash collection company contracted with the city, Waste Management, as they monitor pickups and assess existing staff and equipment in response to rapid growth, Whittenburg told the Fort Worth Report in September.

North Texas’ growing population prompts Fort Worth leaders and company officials to regularly consider equipment and staffing needs, he added.

But with urbanization, other types of waste are burdening Fort Worth’s landfill.

As most waste from businesses are accepted at dump sites, commercial trash leads North Texas’ total waste load by 66%, the council’s data shows.

However, companies generating specific types of waste — sewage sludge, medical waste, scrap tires, batteries, pesticides and paints — must be permitted by state environmental regulators to operate industrial or hazardous landfills.

That process and environmental factors such as air, water quality and land subsidence — the sinking of land most often touted by the removal of water, oil, natural gas or mineral resources — can pose difficulties for developers looking to process waste and operate in North Texas.

Millions of dollars for permitting, environmental risks

Waste trucks dump trash into a pile that is broken down by a steel wheel truck at the southeast landfill in Fort Worth on Oct. 2, 2025. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

Fort Worth and North Texas once had many more dump sites.

After the Environmental Protection Agency enacted more prohibitive requirements for landfills in 1991, most were forced to close.

And obtaining a new landfill permit is no easy feat, which could give would-be operators pause, industry officials note.

“People don’t want to be around landfills. They take a huge amount of land and space,” Ordonez said. “There is a huge cost associated with the development and permitting of landfills.”

On average, it takes about 15 to 20 years for a landfill to receive an environmental permit from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, Lattimore said.

Engineering and soil studies for a potential location can cost anywhere from $30 million to $55 million, Lattimore said. Design and construction adds about another $300 million for every acre of the dump site.

Meanwhile, local officials must consider environmental impacts stemming from landfills, such as water and air quality and land subsidence, said Sahadat Hossain, civil engineering professor and director of the Solid Waste Institute for Sustainability at the University of Texas at Arlington.

Runoff from trash sites can carry contaminants that threaten water quality, human health and wildlife.

Federal guidelines now require landfills to have a protective layer to catch the runoff.

Most dump sites constructed before 1991 did not have those protections, leaving contaminants to come into contact with soil and nearby water sources, Hossain added.

Methane is also a product of landfills when waste comes in contact with water. Landfills, even when they are closed, must be designed in a way that allows those gases to be safely released and monitored.

A greenhouse gas, methane contributes to ground level ozone, or smog, which can cause difficulty breathing and worsen conditions such as respiratory issues, heart disease and cancer.

Left: Methane gas wells are located all around the Fort Worth southeast landfill. Right: A water treatment facility is located at the Fort Worth southeast landfill. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

Captured methane gas is burned into a less harmful carbon dioxide. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

Captured methane gas is burned into a less harmful carbon dioxide. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

“A clear road map”

In July, Tarrant County commissioners made it harder for landfills to process waste in most areas of the county.

They adopted an ordinance establishing specific distances between dump sites and schools, homes and water wells.

While prohibitive, it’s meant to benefit residents and developers, Ramirez said.

“There have been applications for landfills that were filed to build in areas that, 20 years ago, were not developed, but today they are,” Ramirez said. “They’re surrounded by residential communities. It’s not the most suitable place.”

As waste generation grows, the establishment of industrial landfills makes it harder for commercial developers to find safe soil to construct human habitation.

Building homes and public places near or adjacent to landfills must be approached with caution and extensive planning due to the possibility of land sliding and subsidence, which happens when the earth’s surface settles or sinks.

As part of environmental permitting, industrial and hazardous waste sites must fall within a “buffer zone,” which sets limits between dump sites and homes or businesses.

“Because of the growth, cities are growing in all directions,” Hossain said. “Getting a new landfill space is not going to be easy.”

Fort Worth and other Tarrant County cities can look to a variety of options to keep landfills from growing and expanding outward, Hossain said.

For example, Denton had planned landfill mining and rehabilitation at that city’s dump site to extend its life. The process involves the recycling of landfill space after waste has decomposed and eliminates the need for a new dump site. Officials backed off those plans after challenges, such as mounting costs, arose, according to reports.

Driving more recyclable material into recovery stations, particularly paper and cardboard, supports landfills and waste management operations in the long run, Lattimore said.

That’s because recyclable materials are known for their versatile makeup. It is also due to the fact that certain materials, such as cardboard, can be harder to compact.

“By pulling (those materials) out of the waste streams, it benefits the landfills,” he said. “By diverting (recyclables) you not only get that volume out of the landfill, but you increase the density.”

County officials want creative solutions and technology to meet growing waste needs going forward. That includes more transfer stations for short-term waste processing and continued collaboration with partnering governments, including Fort Worth officials, Ramirez said.

“We’re very interested in making sure that the (waste) industry itself has every tool that we can give it to thrive and to serve all of our citizens, because waste disposal and landfills, they’re critical to a functioning society,” he said. “We just have to make sure that they’re not negatively impacting the daily lives of our residents.”

Nicole Lopez is the environment reporter for the Fort Worth Report. Contact her at nicole.lopez@fortworthreport.org.

At the Fort Worth Report, news decisions are made independently of our board members and financial supporters. Read more about our editorial independence policy here.

Related

Fort Worth Report is certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative for adhering to standards for ethical journalism.

Republish This Story

Republishing is free for noncommercial entities. Commercial entities are prohibited without a licensing agreement. Contact us for details.