By the end of 2025, Eva Moreno-Guerrero paid around $15,000 in health insurance premiums to Cigna. After she calculated her family’s expenses – the premiums taken out of her paychecks, copays for doctor visits, out-of-pocket costs because she didn’t meet her deductible – she decided her employer’s health insurance plan was no longer worth it.

The Horizon City resident canceled her plan, which included her husband and two dependent children. Moreno-Guerrero said staying on the same plan would have cost more than $17,000 this year by her calculations. It would be cheaper to pay out of pocket and go to Ciudad Juárez for medical care.

“I’m a bargain shopper, period,” she said. “Was a single mom for a while. I still have groceries, car payments. With groceries going up, it’s going to be brutal. I decided this year we would do without.”

Across El Paso County, 22% of the population have no health insurance, according to a report by the Episcopal Health Foundation in Houston.

Moreno-Guerrero is among the El Pasoans feeling the pinch of pricey plans from employers and the Affordable Care Act marketplace run by the federal government. Policy researchers attribute the rise in health insurance cost to medical services and pharmaceuticals becoming more expensive, the expiration of ACA tax credits and insurance companies expecting a higher proportion of sick people enrolled.

Last year, more than 120,000 people in El Paso County were enrolled in the ACA, also known as Obamacare, according to data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Most people who received health insurance through the ACA, designed for people who do not have employer-sponsored insurance, received tax credits, which lowered their premiums. Enrollees in El Paso paid an average premium of $38 after tax credits compared to $583 without credits.

But Republican lawmakers rejected Democrat-led efforts last year to extend the credits because they object to the government’s role in health care and claim the ACA is rife with fraud. The stalemate led to the longest federal government shutdown in U.S. history.

The House on Thursday approved a three-year extension of ACA tax credits, with 17 Republicans joining the Democrats to revive the legislation. U.S. Rep. Monica De La Cruz of Edinburg was the only Texas Republican to vote in favor of the extension. The bill now faces a rocky road through the Senate.

Screenshot of the federal government’s health insurance marketplace website. Open enrollment ends Jan. 15, 2026. (HealthCare.Gov)

Screenshot of the federal government’s health insurance marketplace website. Open enrollment ends Jan. 15, 2026. (HealthCare.Gov)

“The challenge in the Senate is that there are not enough Republicans who would support a clean extension,” U.S. Rep. Veronica Escobar, D-El Paso, said at a news conference Friday. “I do think the American people need to pressure their senators about supporting a clean extension, but I do know that a small, bipartisan group of senators are working on reforms to the Affordable Care Act.”

Senate Republicans have already said the version of the ACA legislation that passed in the House will not pass in the Senate. Escobar said the Senate may use the bill as a vehicle to pass their own reform and urged El Pasoans to write to Sens. John Cornyn and Ted Cruz to extend tax credits.

The deadline to enroll in the federal marketplace is Jan. 15 for coverage starting Feb. 1.

Why is health insurance so expensive?

Health insurance providers set their premiums based on two main factors: the underlying cost of health care services and who they expect to use those services, said Elena Marks, who studies health policy at Rice University’s Baker Institute. These two factors influence anyone who pays a premium, from employer-sponsored plans to ACA plans to Medicare.

The cost of health care services has increased at a higher rate than wage growth and general inflation as pharmaceutical prices go up, tariffs impact the supply change and rent and overhead costs become costlier, Marks said.

When health insurance becomes more expensive, healthy people will take the risk of going without health insurance, said Brian Sasser, a spokesperson for Episcopal Health Foundation. But people with chronic illnesses, such as cancer and heart disease, will pay more because they need health insurance to live, he said. This makes the proportion of sick people in the coverage pool bigger, which raises premiums for everyone – a process known as the “death spiral” in the insurance industry.

“When the Affordable Care Act was first passed, there was this assumption that young and healthy people didn’t want health insurance, and it turns out that’s not true,” Marks said. “They do want health insurance, but the price point in which they say, ‘Ooh, that’s too much for me’ comes sooner than for someone who anticipates the need for health care.”

Hospitals may not love ACA plans because they don’t pay providers as much as private plans, but they support ACA tax credits because some coverage is better than no coverage, which means providing uncompensated care, she said.

People shouldn’t assume they can’t afford health coverage until they at least look at other options, Marks stressed. Before getting discouraged, people should plug in information such as their income on healthcare.gov to compare plans, she recommended.

How rising health insurance costs strain El Pasoans

Moreno-Guerrero and her son get a checkup a few times a year. She sees a rheumatologist in El Paso twice a year for connective tissue disease, an autoimmune disease that she has stabilized. Her son, who has asthma, sees a pediatrician.

She pays for indemnity insurance through her employer, a national call center, which covers emergency room visits. That plus paying out of pocket for non-ER visits add up to less than what she would pay in premiums, she said. She purchases their medication in Juárez, where her son’s inhaler costs as little as $3 compared to almost $65 in El Paso.

Avenida Juárez is lined with pharmacies that cater to residents of Ciudad Juárez and to El Pasoans who cross the Santa Fe Bridge to find cheaper medication, often without needing a prescription. (Corrie Boudreaux/El Paso Matters)

Avenida Juárez is lined with pharmacies that cater to residents of Ciudad Juárez and to El Pasoans who cross the Santa Fe Bridge to find cheaper medication, often without needing a prescription. (Corrie Boudreaux/El Paso Matters)

Juárez has long provided El Pasoans a cheaper alternative for medical care. Moreno-Guerrero recalled taking her sick daughter to Clínica Santa Clara last year. The visit, which included IV treatment, cost less than $100, she said.

FROM THE ARCHIVES: Study: Internet medicine prices in Mexico 40% cheaper than online in US

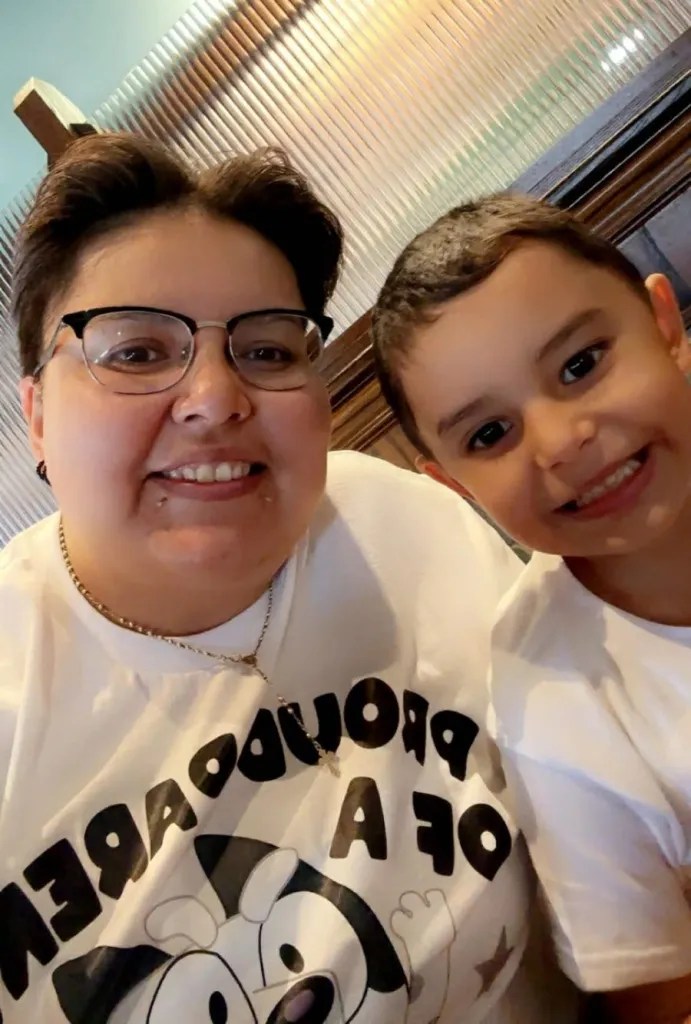

Brenda and Renzo Vargas

Brenda and Renzo Vargas

El Paso resident Brenda Vargas said she enrolled in a private health insurance plan for the first time last year after she no longer qualified for Medicaid. For Vargas, whose 5-year-old son Renzo has autism, canceling health insurance was not an option.

Renzo sees a speech therapist and occupational therapist in addition to his primary care physician. Vargas, who has insurance with Oscar Health, now pays a premium of $280 per month compared to $24 per month last year.

Vargas said she struggled in the beginning to find health care providers who accepted her health insurance. Now that she’s found them and trusts them, she doesn’t want to switch to a different plan and risk searching for new in-network providers all over again.

“I’m going to be budgeting more, spending less,” Vargas said. “I know I can afford it, but the high change caught me by surprise. Honestly, I just got to be cautious of my spending. If I want to go somewhere, I have to think twice. I know I will need that money for my insurance.”

If her premium jumps again next year, she may start looking elsewhere, she said.

“Continuity of care, being able to see the same doctor, see the same clinic, that’s important to people and a factor when people are looking at health insurance,” said Sasser, of the Episcopal Health Foundation.

A survey by the foundation found that more than half of Texans, even with record ACA enrollment last year, skipped health care in some way because of costs. That could mean skipping a prescription or a diagnostic exam, Sasser said.

Health insurance is not simple to navigate, even when people already have it, he said.

FACT CHECK: Can you bring medicine for personal use to the U.S. from Mexico?

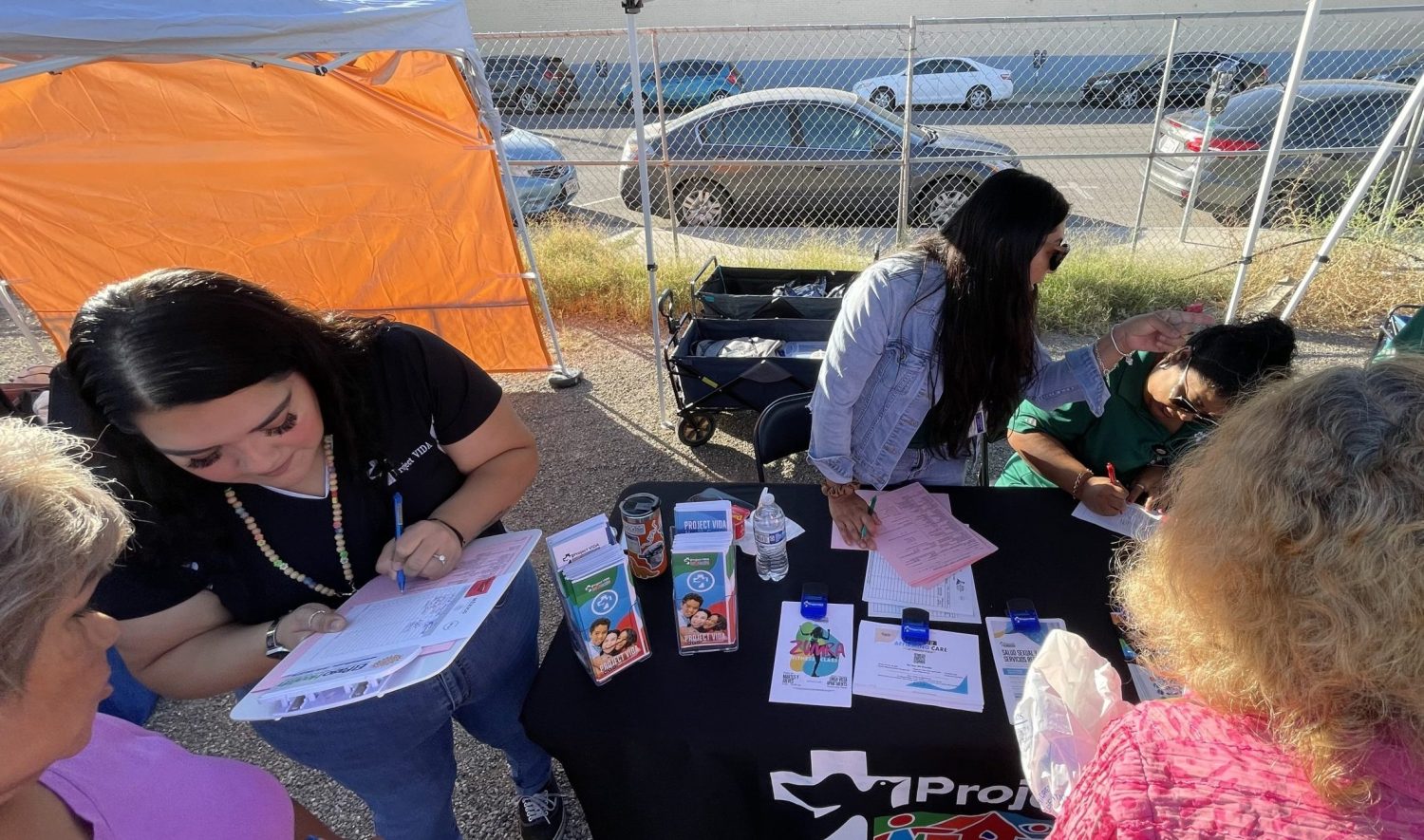

Erin Villarreal, access navigation program manager at Project Vida, helps El Pasoans enroll in the Affordable Care Act. (Courtesy of Project Vida)

Erin Villarreal, access navigation program manager at Project Vida, helps El Pasoans enroll in the Affordable Care Act. (Courtesy of Project Vida)

Project Vida, a health care center in El Paso, saw the number of clients who asked questions about ACA or requested assistance in enrollment drop from 244 to about 130 this enrollment period so far compared with the previous period, said Erin Villarreal, a Project Vida program manager who helps people apply for ACA. Project Vida and other federally qualified health centers in El Paso, including Centro San Vicente, Planned Parenthood and Centro de Salud Familiar La Fe, also provide medical services on a sliding payscale for people without health insurance.

Some clients feel ACA is no longer affordable. Others have come to Project Vida eager to enroll in ACA, only to abruptly change their minds once the process started out of fear their application will flag immigration officials, Villarreal said. Even if people have legal status, if someone in their family does not, they’re worried about drawing attention to their household, she said.

It’s a heartbreaking situation, Villarreal said. The prohibitive cost of health insurance could be the difference between someone with Type 2 diabetes getting their medication or not.

“They start rationing their medication, which further throws diabetes out of control,” Villarreal said. “They have no choice but ER because now they’re dizzy and feeling symptoms of high blood sugar. With lost coverage, it’s like a vicious cycle. I hear real-life stories of people skipping medication or taking medication only when they feel bad, then they feel so bad they go to the ER and can’t even get a follow-up afterward.”

Key Takeaways

The Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare, is a federal health insurance program that offers private coverage through an online marketplace for people who don’t get insurance through an employer. Many enrollees qualify for tax credits that lower monthly premiums based on income.

Healthcare.gov is the online portal for people to browse plans and enroll in the ACA marketplace. People can enter their zip code and answer questions about their household to view estimated prices.

Medicare is a federal health insurance program primarily for people age 65 and older and for some younger people with disabilities. Like with employer and ACA plans, people with Medicare pay a premium, which is influenced by rising health care and prescription drug costs.

Health insurance premiums are increasing as the cost of medical services and pharmaceuticals outpaces inflation and wage growth, and insurers anticipate covering a higher share of people with serious or chronic illnesses.

Expiring ACA tax credits have sharply raised premiums for many El Pasoans, who paid an average of $38 per month last year. Without credits, they would have paid more than $580.

Related

LISTEN: EL PASO MATTERS PODCAST