In a move that has left South Dallas homeowners feeling ignored once again, the City Council voted on December 10, 2025, to approve a controversial Specific Use Permit allowing a 90-foot Verizon cell tower to be built in the historic South Boulevard Park Row district.

He first learned of the proposal from a zoning sign in January 2025, which he says was illegally removed before the CPC hearing. His repeated calls to Verizon, the engineering firm GSS, Inc., and city offices went unreturned. He claims he never received the official notice required for residents within 500 feet.

The tower will stand on a vacant lot at 1814 South Boulevard, owned by Cornerstone Baptist Church, just 60 feet from the home of T. A. Sneed, who has owned the home since 1984 and fought the project for nearly a year. The council’s decision followed a staff recommendation for approval “for a twenty-year period with eligibility for automatic renewals for additional twenty-year periods,” effectively locking in the structure for decades.

The approved item, Z245-145, grants a “new Specific Use Permit for a tower/antenna for cellular communication limited to a monopole cellular tower” within the South Dallas/Fair Park Special Purpose District. Despite Sneed’s appeals and detailed letters to city officials, council members, and even Verizon executives, the measure passed.

The speedy approval of the zoning showcased a stark disconnect between resident concerns and the District 7 Office’s prioritization of business interests. An attorney by trade, T.A. Sneed laid out a detailed case against it.

“The proposed tower would be a stark departure from the character of the 1800 Block of South Boulevard and would undoubtedly diminish my home’s value,” Sneed testified, recounting the area’s purely residential history dating to 1916. He challenged the stated need for the tower, noting that Cornerstone Pastor Chris Simmons, who complained of dropped calls, lives in Cedar Hill and previously acknowledged owning other properties where the tower could be placed instead.

A second speaker, Kimberly Vaughn, argued on procedural grounds, noting the application file lacked critical studies: “It does not include environmental impact study… structural fall zone or hazard assessment… [or] alternative site evaluations.” She urged denial of the SUP or postponing the council vote until such studies were completed.

Their appeals hit a legal wall. When Councilman Bazaldua asked the city attorney about considering environmental impacts, their response: “The cell towers are regulated. We are allowed to regulate the land use only. All of the other aspects of it are regulated by the EPA..”

Deputy Director of Planning & Development Andreea Udrea argued that the application was compatible with the ForwardDallas comprehensive plan and noted that only one letter of opposition was received out of all the notices sent—far below the 20% threshold needed to trigger a higher bar for approval. On pages 20-21 of the zoning case file, it shows that 11 of the 49 notices sent to homeowners within the 500ft radius were sent to the applicant, Cornerstone Baptist Church (22%).

At the City Plan Commission hearing on October 23rd 2025, Sneed challenged the necessity of the tower, pointing to existing infrastructure and questioning why it had to be on a residential block. CPC Chair Tony Shidid acknowledged that if the tower fell, it could land on Sneed’s home or the adjacent Edgewood Manor Senior Apartments, but these concerns were not formally evaluated before the recommendation to approve.

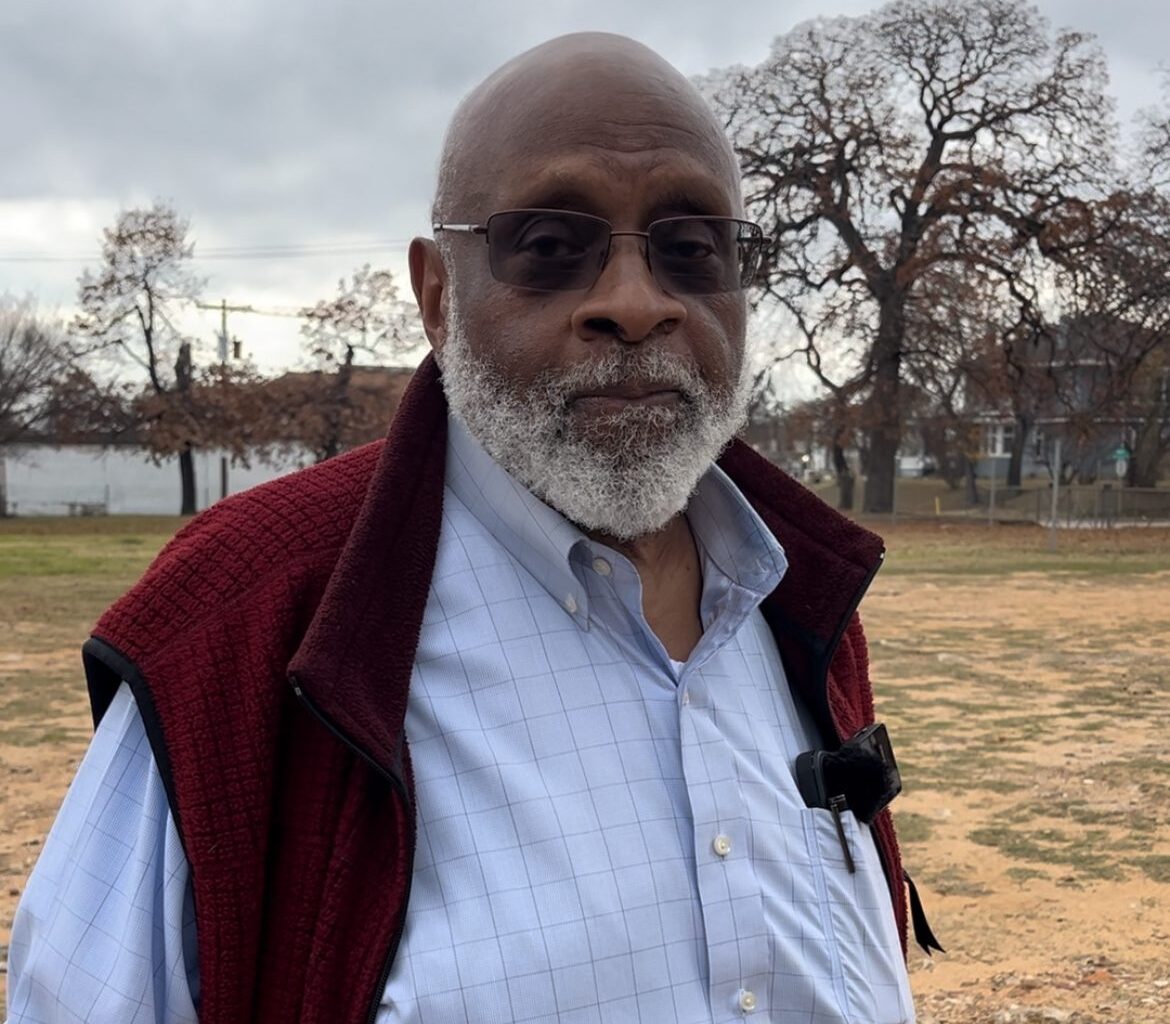

Mr. T.A. Sneed (right) stands at 1814 South Blvd, owned by Cornerstone Baptist Church. To the left, stands his light yellow house. Credit: SiSi Encarnacion

Mr. T.A. Sneed (right) stands at 1814 South Blvd, owned by Cornerstone Baptist Church. To the left, stands his light yellow house. Credit: SiSi Encarnacion

“It’s Not a Whole Lot”: The Church’s Side of the Deal

In a phone interview with Dallas Weekly following the vote, Pastor Chris Simmons framed the tower as a community service. “They kind of reached out to us, actually, two or three years ago… to shore up cell service in the community,” he said. When asked about compensation, he stated the financial benefit to the church as: “It’s not a whole lot…I think it provides $1,200 a month.”

While websites like celltowerleaseexperts.com estimates that cell tower lease rates in Dallas range between $2,560 to $4,820, some would argue that those slim profits are hardly worth the economic and safety risks the tower could pose to the community.

We also reached out to Richard Smith Sr., who is listed as applicant on the zoning case report, to ask about the nature of Cornerstone’s relationship with Verizon. “Yeah I really don’t know…I’m just one of the deacons at Cornerstone.” When reminded that his name was on the application, he responded: “That’s just a formality, Pastor Chris can’t run down and do everything so they just list me as some of the stuff on there.” According to Cornerstone CDC’s website, Richard Smith Sr. holds the position of Senior Property Manager.

A Broader Pattern of Neglect?

Beyond the tower dispute, Sneed and some community advocates point to what they see as a pattern of property accumulation without the corresponding community investment. Dallas County Appraisal District shows that Cornerstone Baptist Church and its affiliated entities own at least 20 properties in Dallas and Mesquite. On South Boulevard alone, Cornerstone owns the tower site (1814 South Blvd) and at least six other adjacent lots, creating a contiguous block of church-owned land encircling Sneed’s home.

The largely tax-exempt real estate portfolios held by a number of churches in South Dallas shift the tax burden onto the few remaining homeowners, many of whom are struggling to stay current themselves. “I’m probably the only guy paying taxes on that block, and the rest of them pay zip” says Sneed. This scenario is an unfortunate example of the extractivism that has left South Dallas feeling barren.

“The issue here is procedural. The record is incomplete,” says Park Row property owner Kimberly Vaughn. The council’s vote confirmed that, in this case, an incomplete record was sufficient. The Verizon monopole will soon rise on South Boulevard as a tall reminder that when institutions and city processes align, the voice of Dallas taxpayers can be rendered little more than a dropped call.

Related