Walter Ned Hollandsworth, who turns 68 in November, was raised in Wichita Falls, the son of a pastor and a school teacher. “No one has any idea why I’m called Skip,” he said recently, sipping an iced tea on the patio of the Chuy’s on Lower Greenville.

Hollandsworth is beloved as a longtime staffer at Texas Monthly, where he writes gripping portraits of Texans who do unspeakable things — the Dallas serial killer who sliced out victims’ eyeballs with an X-Acto blade (Charles Albright), the nurse from Nocona, near the Oklahoma border, who injected patients with a lethal poison (Vickie Dawn Jackson), the pretty young mother from the Houston suburbs who stabbed her husband 193 times (Susan Wright). His dashing persona lies in stark contrast to these grisly tales; he is the kind of quick wit often tapped to emcee galas and moderate Q&As. He looks at home in a tux.

“Did you get that at REI?” I asked of his loose dark shirt with pockets, the kind fishermen wear.

“Oh my God, I do not shop at REI,” he said, in his smooth baritone, and I was left to wonder if REI was too preppy, or not preppy enough.

News Roundups

One of the delights of a Skip Hollandsworth story is learning details mined from his vigorous reporting — the murderous nurse bought her Charlie perfume at Walmart, the knife-wielding mother wore dark red CoverGirl lipstick — so I was reluctant to drop this line of questioning.

“Academy?” I ventured. “Target?” No luck. He didn’t remember where he’d bought the shirt.

In person, Hollandsworth can be something of a lockbox, but his stories open up the world.

‘She Kills’

The nightly news of the late 20th century made its bones on salacious sound bites, a real-life soap opera in which your neighbors might be monsters: There they were on TV, dodging microphones as they fled a courthouse. The longform true crime in Texas Monthly, of which Hollandsworth is a prime practitioner, made its bones on the story behind that story, a more nuanced drama in which the monsters on TV turned out to be real people.

Several Hollandsworth classics are collected in a new book, She Kills, released this month. The book’s unifying theme is female criminals, a statistical rarity, since only 1 in 6 homicides is committed by a woman, according to one of the book’s many postscripts.

Hollandsworth wrote about Susan Wright, left, a Houston mother standing trial for murder, in the Texas Monthly story “193,” named for the number of times she stabbed her husband.

BUSTER DEAN / Houston Chronicle

Hollandsworth wrote about Vickie Dawn Jackson, a nurse from Nocona imprisoned for lethally injecting her patients, in a Texas Monthly story called “Angel of Death.”

GARY LAWSON / AP

But these women have other traits in common. They are often conventionally beautiful — with “movie star long legs” or “a surgically enhanced figure” — and even if they’re not, Hollandsworth finds their beauty. More crucially, they’re described by friends and family as “nice girls.” Marie Robards, a teenager who poisoned her father’s Mexican takeout in 1993, “stayed out of trouble” at her Granbury high school. Peggy Jo Tallas, who disguised herself as a male cowboy to rob small banks in the Dallas suburbs of the ‘90s, took care of her ailing mother in Garland and, as her niece explains, “always came to a complete stop at stop signs.”

“Nothing about their private lives has bubbled up to the surface until this crime has been committed,” Hollandsworth told me. The delicious plot twist of a Hollandsworth saga — the shocking offender lurking beneath the person you only know as good and kind — is more startling when the perpetrator is not male. “Women are supposed to be the gentler sex,” he says, “and if they’re not, what does that say about them and us?”

Jack Black in the 2011 Richard Linklater film “Bernie,” based on a Texas Monthly story by Skip Hollandsworth about an eccentric mortician in Carthage who killed his older wealthy female companion.

Van Redin

Hollandsworth has written about plenty of men, of course, including two profiles snapped up by Hollywood. The 2023 movie Hit Man, starring Glen Powell, followed a mild-mannered professor who goes undercover to catch criminals. The 2011 movie Bernie, starring Jack Black, followed an eccentric mortician in the small East Texas town of Carthage who murdered his wealthy older companion, played by Shirley MacLaine. Richard Linklater directed both, which have the rare distinction of being great stories that became great films.

For his vast contribution to the Texas canon, Hollandsworth has become a literary folk hero, celebrated by the establishment, which has thrown national awards his way, and legions of fans hooked on true-crime podcasts like My Favorite Murder, whose hosts brought him onstage like a rock star at their live show at Irving’s Toyota Music Factory. His close friend, the restaurateur Shannon Wynne, even named a menu item after him at Rodeo Goat. “Murder Burger by Skip Hollandsworth” comes draped like a corpse, with a napkin spattered in red “whodunit” sauce, a knife plunged into the center.

It is not exactly a plot twist worthy of a Skip Hollandsworth saga that the fabled writer turns out to be a pretty normal guy. A one-time Eagle Scout and cellist, he spent much of his adulthood in Preston Hollow with wife, Shannon, and daughters Hailey and Tyler, though more recently, he and Shannon moved to East Dallas. These days, he looks like any other dad and husband walking his golden retriever around White Rock Lake — and yet, there is something mysterious about Skip Hollandsworth, something impossible to identify, because it has not yet surfaced.

Is he so expert at double-identity sagas because he has one? Is he so good at capturing sociopaths and psychopaths because some buried part of him defies explanation, wicked if whisper-soft? Or is he simply so deft at understanding aberrant behavior because he’s so middle-of-the-road? More than once, a mutual friend has told me they’d like to read a Skip Hollandsworth story about Skip Hollandsworth.

“Never gonna happen,” Hollandsworth deadpanned.

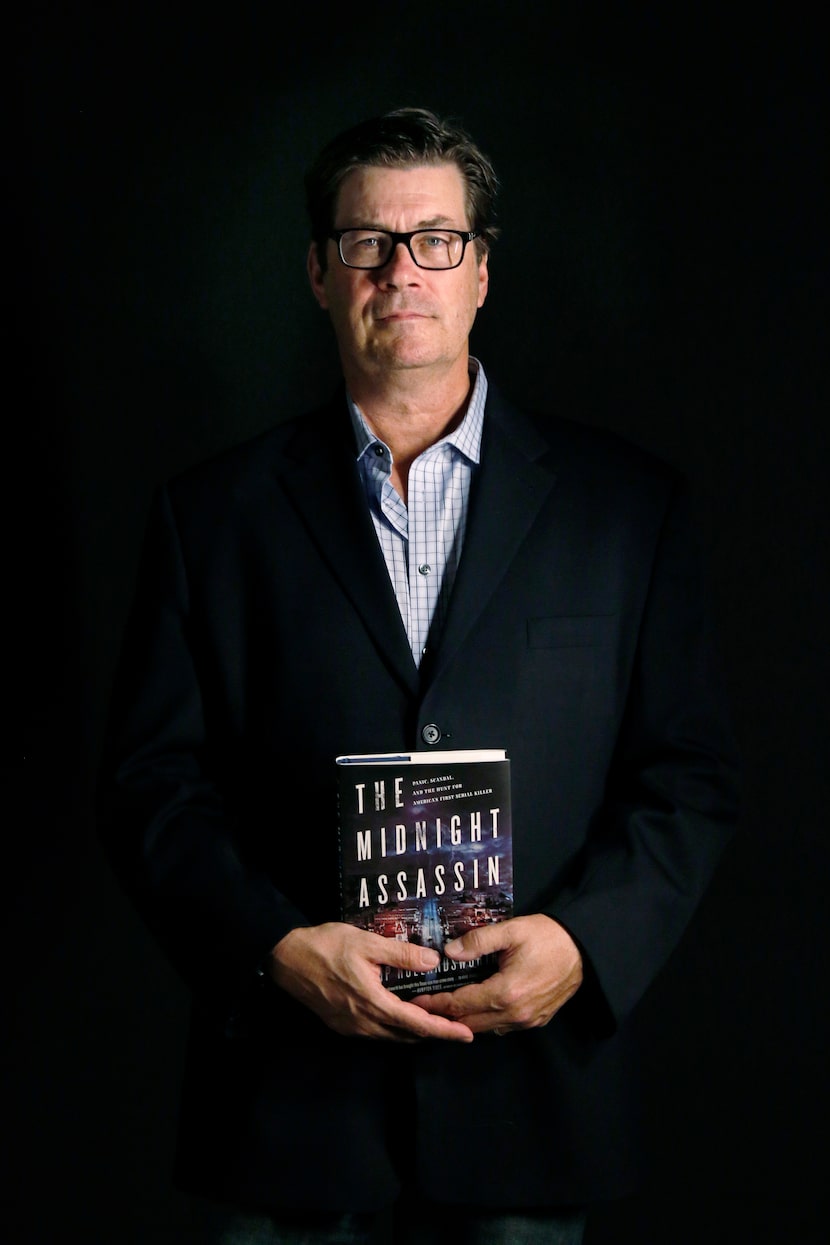

Skip Hollandsworth with his 2016 New York Times bestseller, “The Midnight Assassin,” about Texas’ first serial killer.

David Woo / Staff Photographer

Whatever mystery exists inside the man, he’s keeping it to himself. A few days before meeting him at Chuy’s, a veteran from the Dallas Times Herald, where Hollandsworth worked early in his career, told me staffers used to call him Clark Kent (speaking of secret identities).

“I think I remember that,” Hollandsworth says. “There’s something hazy in my memory that some of those cynical, angst-ridden, arch reporters who didn’t really like anybody called me Clark Kent.”

“Except I was told they called you Clark Kent because you were so handsome,” I said, and he smiled, resting his chin on his hand.

“Well,” he said, “you’re gonna have to choose one for your story.”

My friend Skip

I met Skip in 2012 at a coffee shop on Henderson Avenue. I was in the weeds on a memoir and hoping to siphon inspiration from this titan of letters, whom I’d been assured was nice.

“My only advice is don’t try to be H.L. Mencken and craft some perfect opening line, which is what I try to do,” he told me. I happened to be stuck on my first line, fiddling with each word like a child pushing broccoli around a plate. “Just promise me you’ll finish,” he said, and I did.

Skip Hollandsworth, right, interviews the author at a Mayborn panel in 2017.

Alexis Rosebrock

Over the next years, we met at other coffee shops, sometimes restaurants. In 2016, he wrote his own book, The Midnight Assassin, which became a New York Times bestseller. I’d leave each chat high on his attention only to realize he’d extracted a bundle of information from me — who I was dating, what I was writing, the private ways I was failing — and I’d learned almost nothing about him.

“That is correct,” he said, when I fact-checked this memory with him.

What Hollandsworth will gab about is writing. The craft and the hunt. I actually did extract a bundle of information from those meetings, it just concerned our shared profession. The newspapers he read daily, the leads he followed on a hunch.

“It’s not like anybody ever called and said, ‘There’s this great story in Decatur,’” he told me.

The classic Hollandsworth story

My favorite Skip Hollandsworth discovery began in this paper. One morning, his wife, Shannon, was reading the obituaries when she stumbled on a striking photo she showed to her husband.

“The most handsome teenage boy I’d ever seen,” Skip remembered.

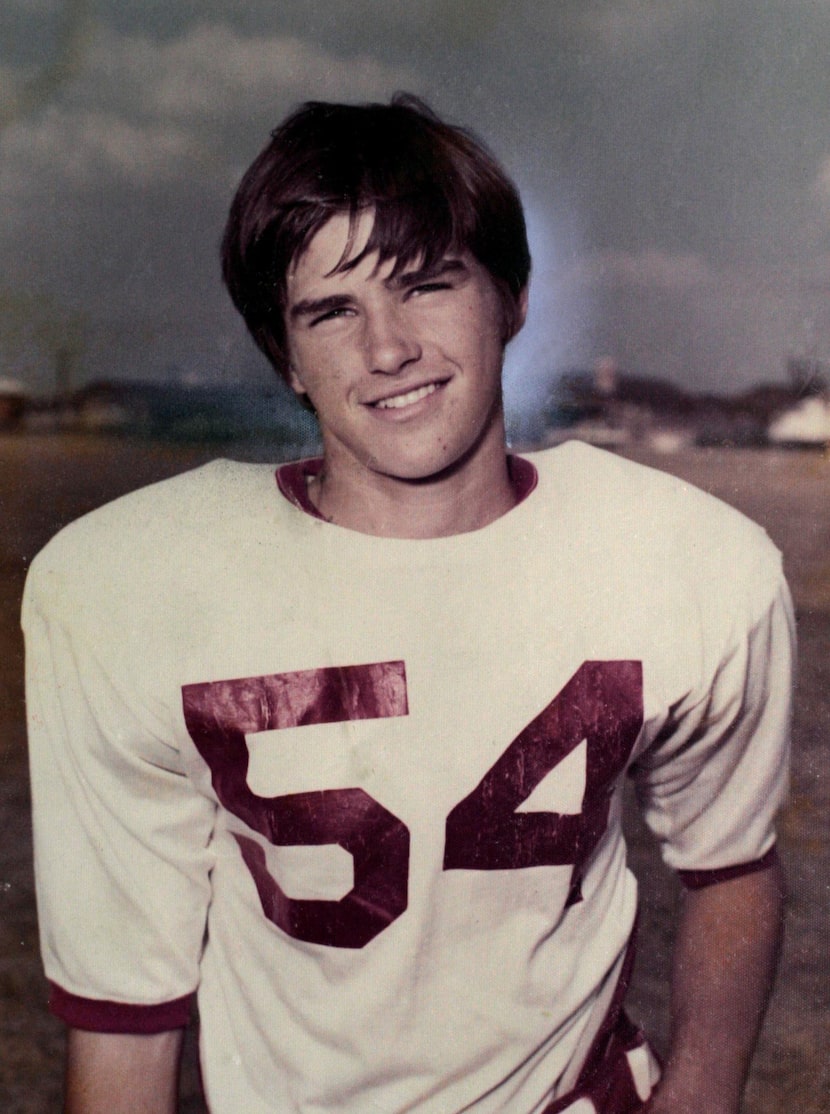

Skip Hollandsworth stumbled upon his 2009 classic “Still Life” when he saw this photo in the DMN obituary of John McClamrock, a Hillcrest student later paralyzed on the football field.

JOHN F. RHODES

In high school, John McClamrock had been a golden god of Texas football, but a violent tackle left him paralyzed. On the day Skip read the obit, he looked up McClamrock’s address, which turned out to be a few blocks away, and when he drove past the house, he saw people coming and going and decided to knock on the door.

What emerged from this intersection of luck and intuition was “Still Life,” winner of the 2010 National Magazine Award, basically the Oscars of magazine journalism. It’s not only a story of the trapped McClamrock, who spent 35 years in the same room, but of the mother who cared for him. A week after Hollandsworth knocked on her door, she died, too.

I felt a combination of elation and frustration whenever Hollandsworth revealed how he got his golden-goose tales. He made it sound easy, but I knew each step could be a land mine.

“Wait, how did they let you in?” I asked of the McClamrocks, as I sipped my Diet Coke at Chuy’s. “You were a stranger.”

“Not if you show some sympathy, you’re not a stranger,” he said. “I’ve never been thrown out of someone’s house who’s suffering a tragedy. I mean, we’ll have a talk, and they’ll say, can you come back? Well, sure.”

‘Skip taught me most of what I know’

Hollandsworth is a polite Texas gentleman, but he has a thick streak of mischief. During my years as a Texas Monthly contributor, he had a habit of alerting me over text whenever a story of mine was slipping in traffic. “You’re losing your edge,” he’d tease me, attaching a screenshot of the Most Read list.

But he has never failed to answer when I’ve sent a distress signal. “I’m in hell, please call,” I’ll text, only to see the phone light up with his name a few minutes later. And over the decades, he’s mentored many other writers coming up through the ranks.

“Skip taught me most of what I know about storytelling,” says Pamela Colloff, a reporter at ProPublica and a staff writer at The New York Times Magazine whose own knockout career (she’s one of the most-nominated women in the history of the National Magazine Awards) began at Texas Monthly. “And still, there’s only so much Skip can teach the rest of us, because what makes him so extraordinary can’t really be taught. He has this disarming, almost wide-eyed charm and a genuine curiosity about other people that makes strangers want to tell him things they shouldn’t.”

Skip Hollandsworth at a Two x Two brunch honoring Richard Phillips in 2012.

NAN COULTER / Contributor – Special Contributor

It’s dangerously easy to spill to Hollandsworth, but part of his skill is how he renders that information on the page, teasing a reader with just enough sizzle. Part of why he likes talking about this so much is that he’s still puzzling out how to do it.

“I’m at that place in life where I want to see the young crowd emerge and find those stories that just make people turn the page,” he told me. “I think about that a lot. Readers have one hand holding a phone. So if you write a sentence, and it’s a little slow, or if the story gets a little dull — the reader is gone.”

The best cliffhanger is often the simplest: What happened next?

So what happened next?

In his prologue for She Kills, Hollandsworth tells the story of getting hooked on true crime when a rich couple in his neighborhood wound up dead, reported in the Wichita Falls Record News as a homicide-suicide. The young Hollandsworth, his imagination fired by Sherlock Holmes, was unsatisfied with this tidy narrative. What if a killer snuck in their home and slaughtered them?

“He could still be here, hiding out!” he recalls telling friends, as he tried to boy detective his way into solving what the police could not. That line went cold, but the storytelling impulse did not.

After graduating from Texas Christian University in Fort Worth, he plied his trade at the Dallas Times Herald and The Morning News, where he got to know both the Dallas socialite scene and society columnist Alan Peppard, whose Rolodex held so many bold-face names it should have been auctioned by Sotheby’s. Hollandsworth’s assignments may have been low-stakes — a quick interview with a celebrity, a dispatch on the bathrooms at the Starck Club — but he was mesmerized by true-crime classics like Vincent Bugliosi and Curt Gentry’s Helter Skelter and Ann Rule’s The Stranger Beside Me, books that rendered the most chilling crimes into the most compulsive reading.

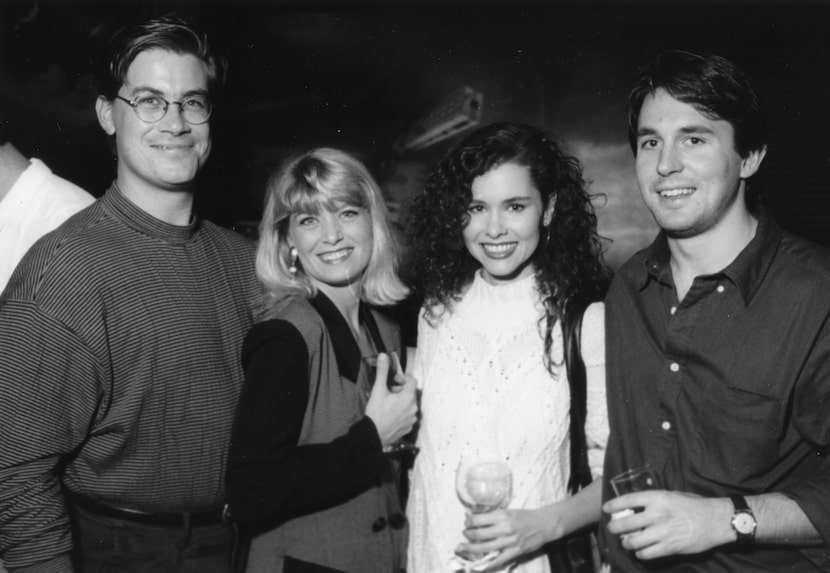

Skip Hollandsworth, left, stands next to his wife, Shannon, at a Dallas party in 1991.

JOE LAIRD/Staff Photographer

It was only after heading to Texas Monthly in 1989 that Hollandsworth began mining this vein. He attributes this to a challenge posed by magazine writer Jim Atkinson, whose tale of Candy Montgomery — another nice suburban wife who cracked, slaying her friend Betty Gore with an ax — became a 1984 book (Evidence of Love, co-written with John Bloom), a 1990 made-for-TV movie and two recent premium-TV serials (Candy on Hulu and Love & Death on HBO).

“Jim looked at me one day and said, you have not made it at Texas Monthly until you’ve written a great crime story,” Hollandsworth said.

And boy, did he ever. The stories that make up She Kills are the tip of a deep and sinister iceberg. At lunch, I suggested future Hollandsworth collections. He Kills could be followed by They Kill, about murderous couples.

“I’ve taken to calling you the grandfather of Texas true crime,” I told him, as I ate from a basket of tortilla chips he did not touch. “Does that make you feel old?”

He chuckled. “No, Sarah,” he said in a playfully wistful tone, “it fills me with the spirit of youth.”

One mystery solved

Over the past few years, a mystery did grow around Skip Hollandsworth, because he’d become scarce. Once a trusty lunch companion, he sent “maybe next month” texts that stretched into next year. He no longer showed up at Arts & Letters Live events, where he’d long been a fixture both on and off the stage. He was harder to find in the pages of Texas Monthly.

Skip Hollandsworth, right, interviews Texas novelist Larry McMurtry at Arts & Letters Live in 2014.

Brad Loper / Staff Photographer

Those searching for a clue might note the sweet and shaggy golden retriever who accompanied him to our lunch. Hollandsworth got his service dog Quixote a couple years ago, after he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, though he adds that he’s so bad at disciplining the dog he’s somehow “untrained” him. Hollandsworth kept his diagnosis under wraps for a long time, but he recently shared it in Texas Monthly.

Parkinson’s has left him slower and more fidgety than he once was. I hardly notice this unless he brings it to my attention. “Is it fun interviewing someone with Parkinson’s?” he asked at one point, his right hand making a twist in the air.

But Hollandsworth has never been less than a giant to me, a writer whose craft I imitate, a man whose generosity I hope to emulate. His stories blossom in the mind because they speak to some of life’s central mysteries: Who is that person living beside me? Living with me? For that matter, who am I?

“I’m more interested in a why-they-done-it than a whodunit,” he tells me.

A whodunit is a riddle solved, but a why-they-done-it is a riddle that lingers in the imagination. Susan Wright, who served 16 years for stabbing her husband, is one that still haunts him. Nurse Vickie Dawn Jackson, who filled syringes with lethal chemicals but was sweet as pie at the local Dairy Queen, haunts me. The nature of good and evil, what humans are capable of when pushed, is a story we’ll be telling until the end of time.

Skip Hollandsworth is still on the case.

‘God’s Country’ meets ‘Rhythm Nation’: How the United Way got Janet Jackson, Blake Shelton

‘God’s Country’ meets ‘Rhythm Nation’: How the United Way got Janet Jackson, Blake Shelton

Five questions with Jennifer Sampson, the dynamic nonprofit CEO who stands tall, in more ways than one.

Hepola: How Amber Fletcher became the Corny Dog Queen

Hepola: How Amber Fletcher became the Corny Dog Queen

Growing up at the State Fair was magic. Stepping into her father’s shoes and overcoming a violent ordeal that happened as a young woman — that was the trickier part.