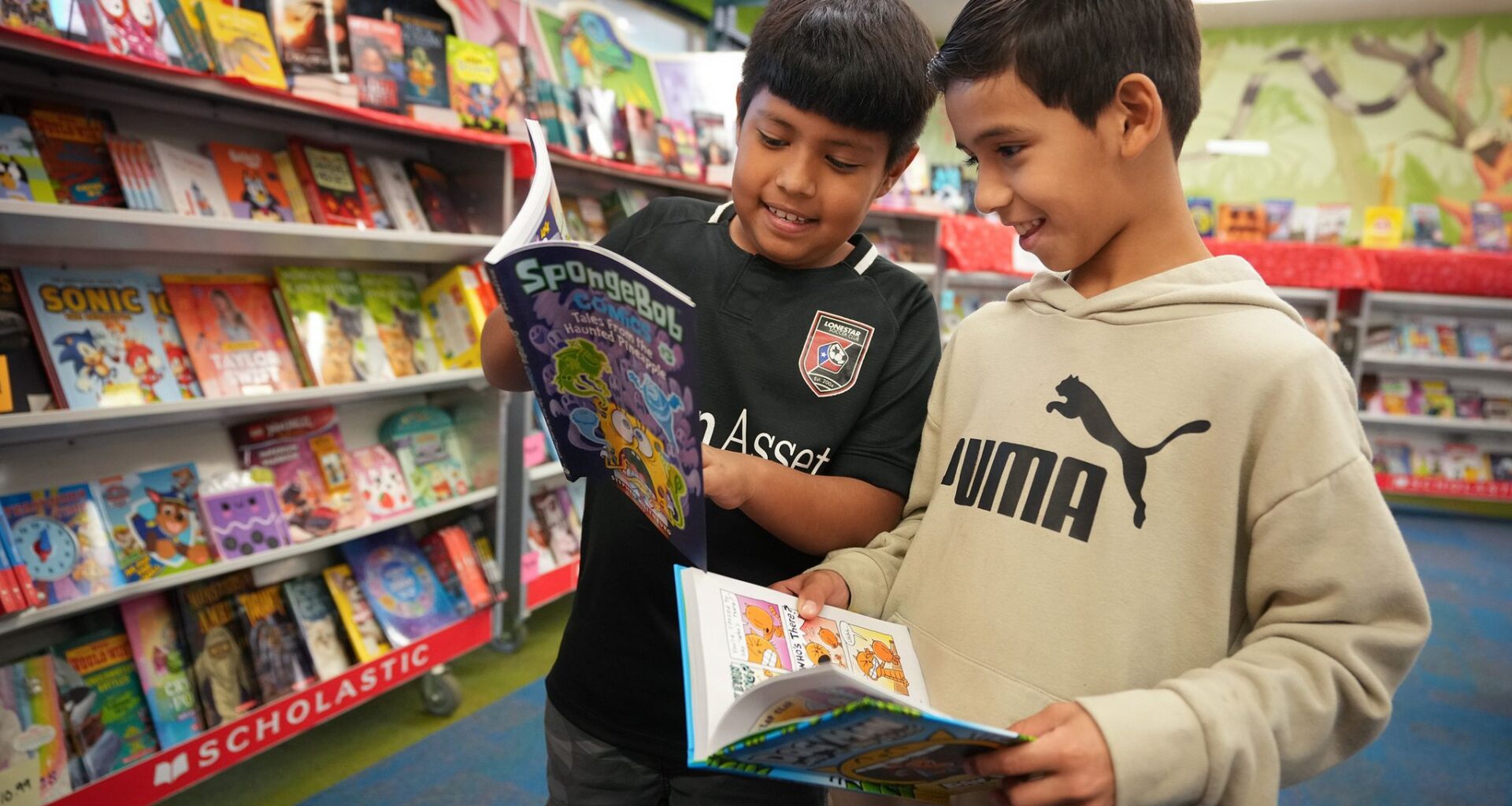

Walnut Creek Elementary School fourth-graders Juan Romo, 10, left, and Lian Lopez, 9, shop in the school book fair on Friday, Oct. 24, 2025.

Jay Janner/Austin American-Statesman

Jessy Reyes didn’t go looking for the neighborhood charter school. Her daughter enjoyed sixth grade at the Austin school district’s Dobie Middle School, where she made friends, learned from her teachers and joined the school band. But in the spring, after hearing from administrators that Dobie could close, Reyes thought she had no other option. She found a charter school and enrolled her daughter there for seventh grade.

The decision was difficult and made her daughter sad to leave behind her friends and clubs, so Reyes was surprised when staff from the supposedly shuttered Dobie called asking about her daughter — the campus hadn’t closed after all. The closure had been widely discussed but was ultimately scrapped after the Rundberg-area school failed to meet state academic ratings.

Article continues below this ad

A kindergarten classroom sits empty at Walnut Creek Elementary School on Friday, Oct. 24, 2025.

Jay Janner/Austin American-Statesman

A kindergarten classroom sits empty at Walnut Creek Elementary School on Friday, Oct. 24, 2025.

Jay Janner/Austin American-Statesman

“They were talking about it closing,” Reyes said in Spanish. “All summer I didn’t hear anything — if it was going to be open, that it wasn’t going to be closed.”

Because of that miscommunication, Reyes’ children became part of the district’s 4% enrollment drop this year.

Fewer than 70,000 students enrolled this fall, the lowest number in three decades and a drop of almost 3,000 from last year, according to data obtained by the American-Statesman.

Article continues below this ad

The sharp decline followed several years of smaller losses and was fueled largely by families leaving the district, even though Austin’s child population has grown slightly, said Victoria O’Neal, the district’s executive director of campus and family engagement. About two-thirds of the students who left last year moved away, she said.

Despite the city’s continued population growth, the district’s student losses aren’t new. Rising housing costs have driven many families to nearby counties such as Williamson, Bastrop and Hays. But this year, the city is also feeling the effect of a nationwide immigration crackdown. Facing fear or financial strain, many Austin families without legal status have left the country. With fewer new immigrants arriving too, local classrooms are thinning further.

But not all factors pushing students away force them out of the city. More than 15,000 students who live within the Austin district attend a charter school — publicly funded campuses that operate independently of traditional districts and have no attendance zones or elected boards.

“There’s been a real self-inflicted wound the district has put upon itself by being vague and uncertain and changing the story for parents — parents who are just trying to figure out ‘Where can I get my kids in school and get an education?’” said Louis Malfaro, associate executive director of Austin Voices for Youth and Education, which provides family support services in low-income schools.

Article continues below this ad

Walnut Creek Elementary School second-graders play soccer during recess on Friday, Oct. 24, 2025.

Jay Janner/Austin American-Statesman

In parts of North and Southeast Austin, charter schools attracted families with specialized education models, flexible schedules, perceptions of higher test scores and aggressive marketing. Public school advocates told the Statesman the district’s communication and recruitment shortcomings have exacerbated the enrollment slide.

Because the state funds schools based on attendance, the district’s dip below 70,000 students will cost money. School board President Lynn Boswell said losing just 72 students equals about $1 million less in funding. The district is currently facing a $19.7 million budget shortfall and has proposed closing 13 campuses and redrawing attendance boundaries for thousands of students.

District leaders have pledged to work with families to stem enrollment loss, but critics fear the school consolidation plan could push even more families to charters or private schools.

Article continues below this ad

The district’s demographers predict another 5,000-student loss over the next decade as birth rates decline and housing costs rise. The state’s new education savings account program, commonly called school vouchers, allows parents to use $1 billion in state funds for private school tuition and could accelerate the trend. Texas families will be able to apply in February and use the money next school year.

The slow drain of students and the rise of charters

Walnut Creek Elementary School students line up for recess on Friday, Oct. 24, 2025.

Jay Janner/Austin American-Statesman

In neighborhoods like North Austin, charter schools have slowly chipped away at district enrollment over the past 35 years.

Article continues below this ad

The number of students living within the Austin school district boundary but attending a charter campus grew from 10,350 in 2015 to about 15,330 last fall. Charter schools are largely concentrated in North, East and Southeast Austin.

Brian Whitley, spokesman for Texas Public Charter Schools Association, said families are drawn to these schools, especially in Austin’s low-income neighborhoods because of their success preparing students for college.

One disadvantage for the district, said Austin Voices staff member Jose Carrasco, is that charters market aggressively, especially in Spanish-language media and through neighborhood mailers.

Article continues below this ad

District spokeswoman Cristina Nguyen said the district doesn’t plan to compete with charters on advertising because of limited resources.

“We don’t have the same investments,” Nguyen said. “We have been cutting and cutting and cutting, and so we just don’t have the same financial setup.”

The district also lacks a standardized outreach program for students who leave district schools but still live locally, leaving each campus largely responsible for promoting itself, O’Neal said. The district plans to strengthen those efforts, but limited staffing remains a challenge.

“It’s just me over the summer,” said Walnut Creek Elementary Principal Giseyla Lopez-Zubieta. “We don’t have anything like where I have the parents or teachers call. I wish I could go door to door and do all that marketing.”

Article continues below this ad

Charter schools, by contrast, use a mix of advertising, community events and word of mouth to recruit students, Whitley said.

A recent blunder

Walnut Creek Elementary School on Friday, Oct. 24, 2025.

Jay Janner/Austin American-Statesman

Poor communication also pushed families toward charters.

Article continues below this ad

In recent weeks, Austin Voices called hundreds of families whose students did not return to three North Austin middle schools in August. Parents like Reyes were common, said Carrasco, who helped lead the project. Many switched to charters after assuming their schools had closed.

At Dobie, Burnet and Webb middle schools in North Austin, multiple years of failing state academic standards forced the district to create turnaround plans for those campuses. The district proposed closing Dobie before reversing course at the end of the school year. District officials said the process was hampered by narrow state-imposed timelines and changing criteria.

Together, the three middle schools lost 334 students this year, though district data shows some transferred within the Austin district.

The uncertainty around the middle schools trickled down to area elementary schools, too. When one child leaves for a charter, siblings often follow, Lopez-Zubieta said.

Article continues below this ad

Reyes’ younger daughter, who was supposed to start kindergarten at Walnut Creek, now attends IDEA Rundberg with her sister. The two girls walk to school hand-in-hand each morning.

Reyes said her older daughter begged to return to Dobie, but she plans to have her children finish the year at their charter campus before deciding whether to move them back to district schools.

Immigration fears and fewer new comers

Walnut Creek Elementary School second-grader Muska Wardak, 7, plays during recess on Friday, Oct. 24, 2025.

Jay Janner/Austin American-Statesman

Austin’s enrollment loss also comes amid an intensified federal immigration enforcement push. The full extent of student loss from departing immigrant families is difficult to pinpoint. Using a survey of 2,000 students who left, the district estimates about 15% left the country, including some who self-deported, O’Neal said.

Article continues below this ad

These moves often follow deportation orders or the removal of a family’s primary breadwinner, said Esmeralda Alday, senior programs director for Texas-based ImmSchools.

In an era of highly limited immigration — with fewer border crossings and a decimated refugee program — the district is also enrolling fewer new arrivals.

In past years, International High School, the district’s high school program for immigrants, welcomed 90 to 100 new students annually; this year, it welcomed just nine, O’Neal said.

Without international immigration, Travis County’s population would have contracted in 2024, Austin city demographer Lila Valencia said.

Article continues below this ad

“School enrollment is an early indicator and a canary in the coal mine of what is to come,” Valencia said.

The long slide

A flag hangs in an empty, unused kindergarten classroom on Friday, Oct. 24, 2025, at Walnut Creek Elementary School where enrollment has dropped 20% year-over-year.

Jay Janner/Austin American-Statesman

Although Austin’s child population has grown, school district enrollment has declined for the better part of 15 years as families — priced out of the city — moved to suburbs.

Article continues below this ad

In the past five years, voters in the Hays, Dripping Springs, Del Valle and Bastrop school districts approved bonds to build new campuses as enrollment surged.

Families with Black and Hispanic children left Austin at higher rates, while the number of Asian and white children grew.

Between fall 2019 to fall 2020, the district lost 6,000 students, part of a nationwide post-pandemic decline.

Across the country, enrollment could drop another half a percent annually for the next decade as birthrates fall, according to Georgetown University’s Edunomics Lab. In Texas, overall student growth since 2019 was concentrated in charter and suburban districts, according to a Texas A&M University study. Nearly 60% of Texas’ traditional school districts are shrinking, the June study found.

Article continues below this ad

With closures ahead, district continues on uncertain path

The district could face another shock next summer as administrators implement a sweeping proposal to close 13 campuses and redraw attendance boundaries for 75% of students.

Some parents have already threatened to look outside the district for the 2026-27 school year.

“We have to hang onto everyone we can and we have to invite new people in,” Boswell said. “I don’t think that means we don’t have to go through closures. I don’t think that means we don’t have to go through this really painful process. I just mean we need to be aware and thoughtful.”

Article continues below this ad

District administrators argue that having fewer schools will make it easier to distribute resources, said Ali Ghilarducci, senior executive director of communications and community engagement.

The district also plans to hire an additional front office staff member for each campus that’s under a turnaround plan, Ghilarducci said.

The city of Austin is working to expand affordable housing, but unless it acts decisively, families will likely continue leaving, Valencia said. Last week, Mayor Kirk Watson announced the “Generation ATX” initiative to improve Austin’s quality of life for children.

But fewer than half of Austin’s households now include children, she said. Austin leaders will have to be strategic about creating a family-friendly culture, she said.

Article continues below this ad

“Oftentimes, when we do that,” Valencia said, “we get an additional diversity that appeals to more people.”

This story has been updated to correct the percent change in student enrollment.