Angelica Hernandez felt anxious in the days leading up to Tuesday, Oct. 28. But when she entered that familiar courtroom, the same one she had stepped into every month the past year Hernandez knew she was ready for the next step.

Hernandez, 47, became the first person to graduate from El Paso County’s INSPIRE Mental Health Court, spearheaded by Judge Selena Solis in the 243rd District Court.

The 12-month rehabilitation and prison diversion program takes in people with felony offenses and serious mental illness, such as bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and major depression. Many of the participants have a co-occurring substance-use disorder and almost all of them have violated probation.

State law requires counties with a population of 200,000 or more to establish a mental health court program.

“It’s going so deep down into your core to figure out where all this comes from,” Solis said. “By throwing people in prison and in jail, you’re not changing their lives. They’re not learning anything … And they’re gonna come back out, whether it’s three years, five years, eight years – and they’re gonna do the same thing.”

Angelica Hernandez, front left, celebrates her graduation from a diversion program that works to support the mental health needs of individuals in the criminal justice system, with a ceremony at the El Paso County Courthouse, Oct. 28, 2025. (Luis Torres/El Paso Matters)

Angelica Hernandez, front left, celebrates her graduation from a diversion program that works to support the mental health needs of individuals in the criminal justice system, with a ceremony at the El Paso County Courthouse, Oct. 28, 2025. (Luis Torres/El Paso Matters)

El Paso County established its mental health court – whose acronym stands for Independence, Namaste, Safety, Purposeful, Insightful, Resilience and Empowerment – in fall 2023 after receiving a $200,000 state grant from the Office of the Governor. The annual grant was renewed Sept. 1, 2024, for $220,000. The funds go toward personnel and resources that support each participant, including a program coordinator, counseling and transportation services such as bus passes.

Solis said her goal is for participants to reintegrate into society and stay out of the criminal justice system after they leave the program.

Angelica Hernandez celebrates her graduation from Shadows to Light, a diversion program that works to support the mental health needs of individuals in the criminal justice system, Oct. 28, 2025. (Luis Torres/El Paso Matters)

Angelica Hernandez celebrates her graduation from Shadows to Light, a diversion program that works to support the mental health needs of individuals in the criminal justice system, Oct. 28, 2025. (Luis Torres/El Paso Matters)

The hardest part is just showing up, Hernandez said.

To reach completion, each participant must comply with an individualized treatment plan and make their appointments with an extensive team that includes a case worker, doctor and probation officer. Participants must also stay on top of counseling, group classes, medication, drug testing, community service and employment.

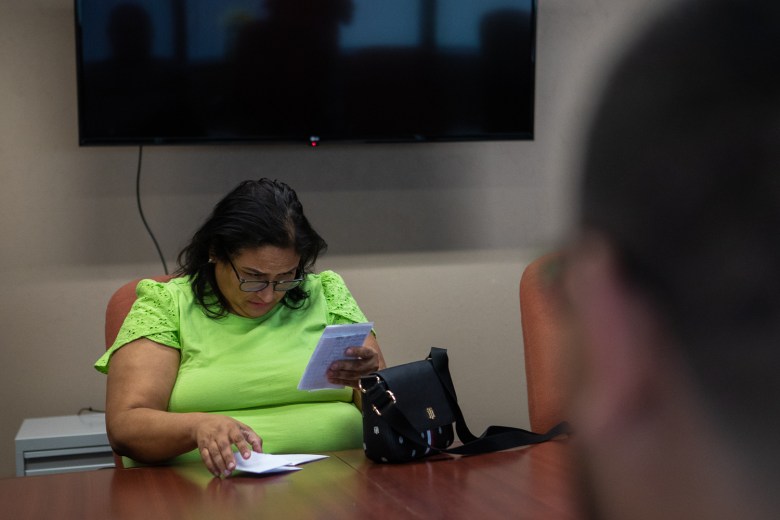

Months prior to the graduation ceremony, Hernandez met with El Paso Matters on the ninth floor of the County Courthouse. She pulled out folded sheets of paper from her purse as she waited for one of her court-mandated classes to begin.

The pages contained the first draft of a letter she was writing to Solis, reflecting Hernandez’s past year in the INSPIRE Mental Health Court. In 2023 Hernandez was charged with aggravated assault with a deadly weapon. The weapon was the car she was driving when she crashed into another vehicle during her suicide attempt.

Angelica Hernandez, who expects to be one of the first graduates of the Shadows to Light program, pulls out an essay she has been working on as one of her final assignments, June 10, 2024. (Corrie Boudreaux/El Paso Matters)

Angelica Hernandez, who expects to be one of the first graduates of the Shadows to Light program, pulls out an essay she has been working on as one of her final assignments, June 10, 2024. (Corrie Boudreaux/El Paso Matters)

She broke down in tears as she recalled the collision, choking up as she expressed relief that the couple in the other vehicle survived, though the wife broke her hand in the crash. She faced the couple again before her sentencing in October and said she felt remorseful for what she put them through.

“I’m glad nothing happened to them, but they did crash their truck,” she said, her voice becoming quiet. “The past follows me, but I’m not giving up. I’m taking it day by day.”

Getting a second chance

Hernandez, a mother of three, was diagnosed with bipolar disorder at the El Paso Psychiatric Center. She also has depression and anxiety. She began taking psychiatric medication until a few years ago when a general practitioner determined that Hernandez could stop. That’s when her struggles resurfaced.

Her thoughts suffocated her. She felt overwhelmed trying to hold a job while taking care of her son, who had seizures, and her mother, who had arthritis and was unable to walk on her own. She eventually quit her job to focus on care taking, but the bills piled up – along with feelings of worthlessness and hopelessness.

In 2023, Hernandez was charged with a felony after she experienced a mental breakdown and crashed the car she was driving in an attempt to take her own life, hitting a truck in the process. The people in the truck survived and after her release, Hernandez went to jail.

In 2024, she picked up another assault charge, which led Hernandez’s attorney to refer her to the INSPIRE Mental Health Court. After Hernandez completed the program, Solis dismissed this case and sentenced Hernandez to probation for her prior case.

Angelica Hernandez poses at the El Paso County Courthouse on June 10, 2024. Hernandez, who expects to complete Shadows to Light in July, will be one of the first graduates of the program. (Corrie Boudreaux/El Paso Matters)

Angelica Hernandez poses at the El Paso County Courthouse on June 10, 2024. Hernandez, who expects to complete Shadows to Light in July, will be one of the first graduates of the program. (Corrie Boudreaux/El Paso Matters)

Hernandez wrestled with shame and grief earlier in the program. Her mother died last year in a nursing home. She had lost her license because of traffic tickets. Employers stopped responding when she applied for jobs as one of the program’s requirements, her criminal history front-and-center in every background check.

But eventually she began to feel stable after maintaining her medications. Counseling gave her someone to talk to about everyday struggles. She passed her driver’s test again and has worked at a restaurant for two years now. Hernandez said she’s no longer afraid her old tendencies will come back.

“There are a lot of people in El Paso with mental health problems,” Hernandez said. “The INSPIRE court gave me a second chance, and sometimes that’s all people need to come out stronger, to realize how precious life is and how much your kids need you.”

Mental health court: Rehab over punishment

The INSPIRE Mental Health Court joins other specialty courts in El Paso, such as the DWI Drug Court, that provide an alternative to incarceration.

The state’s government code first defined criminal mental health courts in 2003, but back then, few judges wanted to take on the additional responsibility of a mental health court, said Oscar Kazen, a former criminal judge and now probate judge in Bexar County. He serves alongside Solis as a commissioner on the Texas Judicial Commission on Mental Health.

In 2007, Kazen established the state’s first assisted outpatient treatment program in civil court.

“Twenty years ago, if you said you wanted to be a mental health court judge, they said go be a counselor. If you want to be a judge, be a judge,” Kazen said. “We were coming from the tough on crime, hang ’em high culture.”

Participants in Shadows to Light, a diversion program in El Paso County’s INSPIRE Mental Health Court that works to support the mental health needs of individuals in the criminal justice system, attend the graduation of Angelica Hernandez, the first person to complete the program, Oct. 28, 2025. (Luis Torres/El Paso Matters)

Participants in Shadows to Light, a diversion program in El Paso County’s INSPIRE Mental Health Court that works to support the mental health needs of individuals in the criminal justice system, attend the graduation of Angelica Hernandez, the first person to complete the program, Oct. 28, 2025. (Luis Torres/El Paso Matters)

Today, there are more than 30 mental health courts for adults in Texas, according to the state’s list of registered specialty courts.

The El Paso court has not received funding for this current fiscal year while its application is still pending under review, but the team expects to get notification by the end of the year, said court coordinator Monica De La Cruz. In the meantime, the county is funding the program until the end of the calendar year or until receiving the state grant, De La Cruz said.

The INSPIRE Mental Health Court has taken in 14 participants since it began in 2023, their charges ranging from robbery to possession of a controlled substance.

Solis said getting the program off the ground is the first big challenge and after speaking with other specialty court judges in Texas, she learned it can take programs three years before seeing their first graduate.

“It’s trial and error, basically,” Solis said.

One of the ways to measure a program’s success is to look at the recidivism rate, or the rate of graduates who commit crimes again. But statewide analysis of recidivism for specialty courts is difficult because of “missing, incomplete or erroneous identifying data,” according to one state report.

El Paso Matters requested recidivism rates from several mental health courts in major Texas counties, but found programs varied in how they defined recidivism and how they collected data.

Kellie James, a participant in the Shadows to Light program, waves as he disappears into a secure area of the El Paso County Courthouse to attend his group meeting, June 10, 2025. (Corrie Boudreaux/El Paso Matters)

Kellie James, a participant in the Shadows to Light program, waves as he disappears into a secure area of the El Paso County Courthouse to attend his group meeting, June 10, 2025. (Corrie Boudreaux/El Paso Matters)

The Bexar County Mental Health Court, which handles misdemeanor cases, has had more than 500 graduates – more than half of all participants – since it began in 2008, according to statistics provided by the program manager.

The presiding judge, Yolanda Huff, said one of the most critical lessons she learned is participants will relapse if they have to return to a toxic home environment straight after inpatient treatment.

The program now asks patients with co-occurring substance use disorder to stay in a sober living home, Huff said. Participants who are in abusive relationships attend classes to learn about healthy relationships.

More than 500 people with misdemeanors have completed the Bexar County Mental Health Court. (Courtesy of Judge Yolanda Huff)

More than 500 people with misdemeanors have completed the Bexar County Mental Health Court. (Courtesy of Judge Yolanda Huff)

Sober-living placements are limited, however, and not all facilities are equipped to handle clients with both mental health and substance use issues, said Brock Thomas, the visiting judge who presides over the Harris County Mental Health Court for felony cases. This, combined with high caseloads, puts pressure on the court’s ability to serve when there are more people in need than resources available, he said.

The Harris County Mental Health Court, which began tracking enrollment in 2013, has had more than 200 graduates – also more than half of all participants, according to statistics provided by a county spokesperson.

The goal isn’t for people to just complete their probation, Thomas said. Mental health court graduates have been able to find stability and independence. Some are able to reunite with their families and regain employment, he said.

“We’ve learned recovery is not linear – and we’ve built our program around that fact,” Thomas said. “Stabilization takes time, and setbacks are part of the process.”

Criminal justice program relies on partnerships, long-term funding

Until this fall, El Paso’s INSPIRE Mental Health Court was entirely state grant funded. That’s different from the Bexar County Mental Health Court, which is budgeted in the county’s general fund, and the Harris County Mental Health Court, which was created under a federal grant and now funded by the county.

Solis said she would “absolutely” ask El Paso County Commissioners Court for more funding in the future, but it’s a tricky time because of the county’s budget shortfall.

She would like to see more input from the District Attorney’s Office and collaboration with more community partners, she added.

Participants in the Shadows to Light program gather for a group meeting at the El Paso County Courthouse on June 10, 2025. (Corrie Boudreaux/El Paso Matters)

Participants in the Shadows to Light program gather for a group meeting at the El Paso County Courthouse on June 10, 2025. (Corrie Boudreaux/El Paso Matters)

One of the mental health court’s partners is the Philosophic Systems Institute, which runs Shadows to Light, an educational program.

While participants spend time talking about what they’re going through, the sessions are more like a classroom for problem solving and emotional skills – Shadows to Light coordinators are not therapists or counselors, said Mika Cohen, vice president of the Philosophic Systems Institute.

In one class, participants might bring in the lyrics to their favorite song and explore why music is a source of strength or comfort in times when they’re struggling, Cohen said

In another class, participants might learn about meditation and breath control.

“At the top of the resiliency skills list a lot of times is knowing when to ask for help… knowing when to have a sounding board and insert a pause right before thinking or acting,” Cohen said. “Being able to control your breath, and insert that pause, just a few seconds sometimes is enough to keep us from making a really bad choice.”

Hernandez admitted that she saw these classes, as well as individual counseling, as more tasks to worry about at first. But opening up has made her feel less alone, less trapped in her head.

“Hearing other people, what they’re going through, helps also,” she said. “Sometimes you fear you’re the only one who messes up, but other people do too, for one reason or another.”

Related

LISTEN: EL PASO MATTERS PODCAST