With a looming water supply shortfall, the Corpus Christi, Texas city council shut down design work on a planned desalination plant in September, stopping early work and terminating a $50-million design contract awarded to Kiewit.

The reason? At only 10% design completion, the city council learned that Kiewit and the Corpus Christi engineering consultant had most recently projected the final plant cost at $1.2 billion. Only 10 months earlier, after Kiewit had won a three-way competition for the design-build contract, the city and its engineers were using $757 million as the price estimate. More design work was needed before a final contract with a guaranteed price could be signed.

Price quotes prior to the post-2019 burst of construction inflation, and before an expansion of the planned plant capacity, had put the cost at only $220 million.

Now the council, other elected officials and city-owned water utility Corpus Christi Water are scrambling to come up with solutions that include securing water from other water districts, drilling for new water sources—and reportedly restoring the cancelled contract.

The increases baffled and upset city council members and local residents who discussed the matter at an emotional meeting on Sept. 2. “I just can’t wrap my head around $1.2 billion,” said Councilman Eric Contu, who voted for termination. “Whoever decided to go design-build, they screwed up. They could charge whatever they want at 30 or 40 or 60 percent.”

Other council members said they were unhappy that Kiewit, with its contract suspended, chose to send only observers rather than testify at the meeting. But other local residents, council members and officials of Corpus Christi Water did not target the delivery method, contract type or Kiewit.

The project’s price had increased partly because of rapid inflation in recent years, said officials of Corpus Christi Water, and capacity added to the original desalination plant concept. Ratepayers will pay more no matter which course is taken, and cancelling the desalination plant project is certain to add to costs.

Drew Molly, former chief operating officer of Corpus Christi Water, wrote to City Manager Peter Zononi in August that cancellation would leave the city “without a fully

permitted alternative,” adding that timing of new permits is unpredictable and higher water rates would fall on individual ratepaying homeowners, beginning with an increase of about $96 per year.

Molly, a licensed engineer, recently resigned from his position at Corpus Christi Water to take a new job in Houston.

Drew Molly, former chief operating officer of Corpus Christi Water, testified at the emotional council meeting that resulted in a vote to terminate Kiewit’s contract.

Some residents were already upset about the city’s decision to site the plant in the Hillcrest section. Other residents, some wearing blue “Water for People, not Polluters” T-shirts, emphasized that industrial companies consumed much of the city’s available water supply and wanted still more.

Faced with bleak alternatives, several speakers and council members sought, as some put it, to cut their losses, while others believed it was wiser to restore the Kiewit contract until 60% design was reached next year.

Bringing in the second-place finisher in the desalination plant competition would push the design completion back by another three to four months, Zononi said.

Several citizens and some council members suggested that, at 60%, the design completed by Kiewit could be put out to bid to another firm in the hope of getting a better price. Whether that is possible isn’t clear.

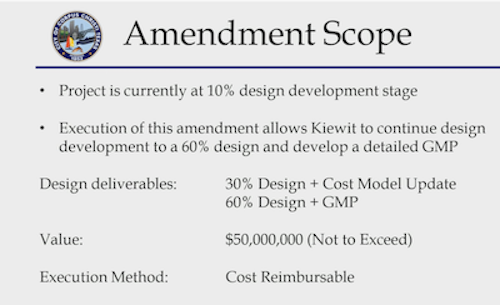

A slide was shown to Corpus Christi City Council members about the choice they faced in deciding whether to continue or terminate the city’s agreement with Kiewit.

Mayor Paulette Guajardo, who advocates to continue the project, said terminating Kiewit’s contract—which the city had already suspended in the previous month—would be flushing $50 million “down the toilet.” The comment implied that the money had already been paid or obligated for the desalination project use only.

A year ago, the project still had no settled price. But the city selected Kiewit Infrastructure South Co., which bested two competitors to design and build the Inner Harbor Desalination Plant. Local leaders estimated the project’s cost at $757.6 million.

The seawater desalination plant would have a capacity of 30 million gallons per day. Corpus Christi Water planned to build the plant at a site beside the Inner Harbor ship channel, which links the Port of Corpus Christi to the Gulf of Mexico. The plant would both draw from and discharge into the channel.

The contract with Corpus Christi Water, which the city owns, called for the project to be delivered under a progressive design-build approach, where close cooperation during design development culminates in a fixed price at 60% of the design.

What the $50 million in design development was paying for could be seen in presentations to the city council and Kiewit’s description of the costs of delaying. With no work performed by Kiewit in August, 30% design development was scheduled to take until mid-November. Not until the end of February 2026 would 60% design be reached and review by the city council would not occur until March.

In late August, while its contract was suspended, Kiewit made the case to continue the contract and avoid a costly delay or interruption of its work.

In an email to Corpus Christi Water, the company listed the consequences of delay. One of the biggest costs is work interruption to other utility staff currently working on the project. Kiewit stated in an email that at the time of the memo, that it had more 100 managers, engineers and craft employees assigned to the project. This was communicated to Brett Van Hazel, project office director for Corpus Christi Water.

Engineering firms working on the project, such as Arcadis and GHD, employed another 50 people devoted to the project. Those engineering firm staff would lose efficiency and continuity with a further suspension of work, Kiewit stated. With the Texas market booming, Kiewit staff would have to quickly be assigned to other projects, the company wrote.

Arcadis noted that design and cost validation under progressive design-build were meant to take place in “lockstep.”

A demonstration plant also had to be built as part of design and cost planning. Any delay in ordering long-term lead items from a variety of specialized equipment firms also would push project completion further back and likely lead to higher prices, Kiewit warned.