Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

By the fall of 2021, predictions of steep declines in students’ learning due to pandemic school closures had come true. Gaps between the highest and lowest learners were widening.

That’s when a large suburban school district in Texas, flush with COVID relief funds, signed a contract with a virtual tutoring provider to deliver extra help to students in 28 schools who had fallen below grade level. Research showed that high-dosage tutoring could produce significant gains for students and was far more effective than on-demand models.

But the district’s program didn’t work, according to a recent study from Stanford University’s National Student Support Accelerator, which focuses on studying and expanding effective tutoring. Students even lost ground in reading and would have been better off with “business-as-usual” support, like small group instruction or using a computer program for extra practice.

Experts view the findings as a cautionary tale of how tutoring can go wrong.

The district had to wait on background checks for tutors, many students were still chronically absent and the tutoring sessions often conflicted with other lessons or special events. As a result, students didn’t receive the 30 hours or more required under a state law mandating tutoring for those who failed the annual state test. Instead of five days a week as planned, 81% of the students attended tutoring three or fewer days, and most students worked with a different tutor every time they attended a session.

Related‘Put Your Money Where Your Mouth Is’: Indiana Wants Reading Gains Before Paying

The findings reinforce the importance of protecting the time students are supposed to receive tutoring, said Elizabeth Huffaker, an assistant professor of education at the University of Florida and the lead author of the study.

High-dosage models — featuring individualized sessions held at least three times a week with the same, well-trained tutor — can still “drive really significant learning gains,” she said, “but in the field, things are always a little bit more complicated.”

For parents, the Stanford study can help explain why children might not make gains, even when their district offers extra help, said Maribel Gardea, executive director of MindShiftED, a nonprofit advocacy group and network of about 5,000 parents in the San Antonio area. Despite the billions states received in relief funds, many students still haven’t reached pre-pandemic levels of performance.

“We knew that high-dosage tutoring was one of those things that was proven,” Gardea said. “There was research, but we never saw those results.”

She urges districts to include parent groups like hers in planning tutoring and choosing providers. But she added that too many parents are unaware their children are behind, much less equipped to judge whether a program is set up for success.

“The trust has been lost for such a long time,” she said. “Parents just send their kids to school and they hope for the best.”

‘It’s logistics’

The results add to a growing body of research at a time when tutoring has shifted from being viewed as an emergency stopgap to an ongoing teaching strategy, according to a report released last week from Whiteboard Advisors, a consulting organization.

The authors’ interviews with state and local education leaders, researchers and tutoring providers showed that while many schools lean toward in-person tutors, “effective virtual models persist” in many districts. Going forward, they expect more schools to use tutoring as a pipeline for recruiting and training new teachers.

Districts have learned a lot about tutoring since that first, full year back after school closures, one in which districts saw staff shortages, record levels of absenteeism and disruptive behavior from students. Multiple states have passed legislation to support tutoring or provide at least some short-term funding to keep programs running now that federal relief funds have expired. Some districts, including those in Texas, are designing contracts that reward tutoring providers with more money when students pass tests or make other significant gains.

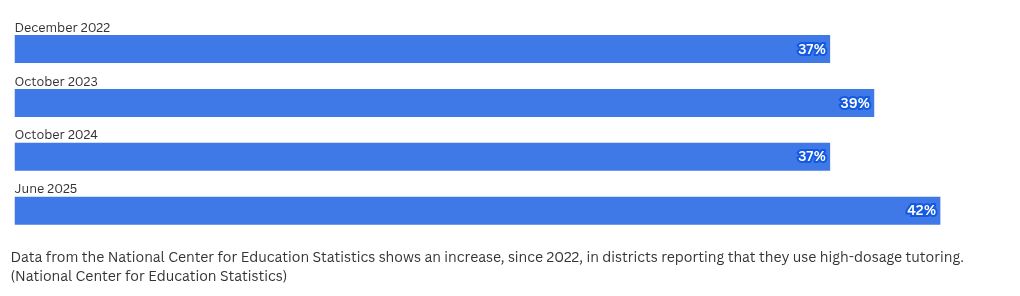

Recent federal data shows an increase since December 2022 in the share of schools offering high-dosage tutoring, from 37% to 42% — especially in the South. But the results of the study show that just giving tutoring a high-dosage label doesn’t mean students will receive the help they need.

“It’s logistics,” said T. Nakia Towns, chief operating officer at Accelerate, which funds research on tutoring and other recovery efforts. “You have to have the scheduling. You have to have the identification of the students.”

High mobility, absenteeism

To encourage the tutoring provider and the Texas district to participate in the study, the researchers didn’t identify them. But an official with the district, who spoke on background, told The 74 that one reason tutoring didn’t start until the middle of the school year was because leaders waited for winter test data to ensure they were selecting students who needed the most help.

The state required tutors to pass federal background checks, a process that added delays, and it took time to find bilingual tutors and those with special education experience. Students who were furthest behind academically “were also the same students who had high mobility or high absentee rates,” the official said.

School assemblies interfered with the tutoring schedule, and some principals, the official said, were less supportive of virtual tutoring in general. Now, he said, the district offers in-person afterschool tutoring as one option, but also builds intervention time into the school day for all students.

RelatedAs Chronic Absenteeism Persists, Schools Launch New Efforts to Reduce It

Tutoring during school hours increases the chances that students will actually get the service, but the model creates some challenges, Huffaker said. Tutoring is now “competing with other instructional practices during the school day.”

That includes lessons that teachers are presenting to the whole class and don’t want students to miss, the district official added.

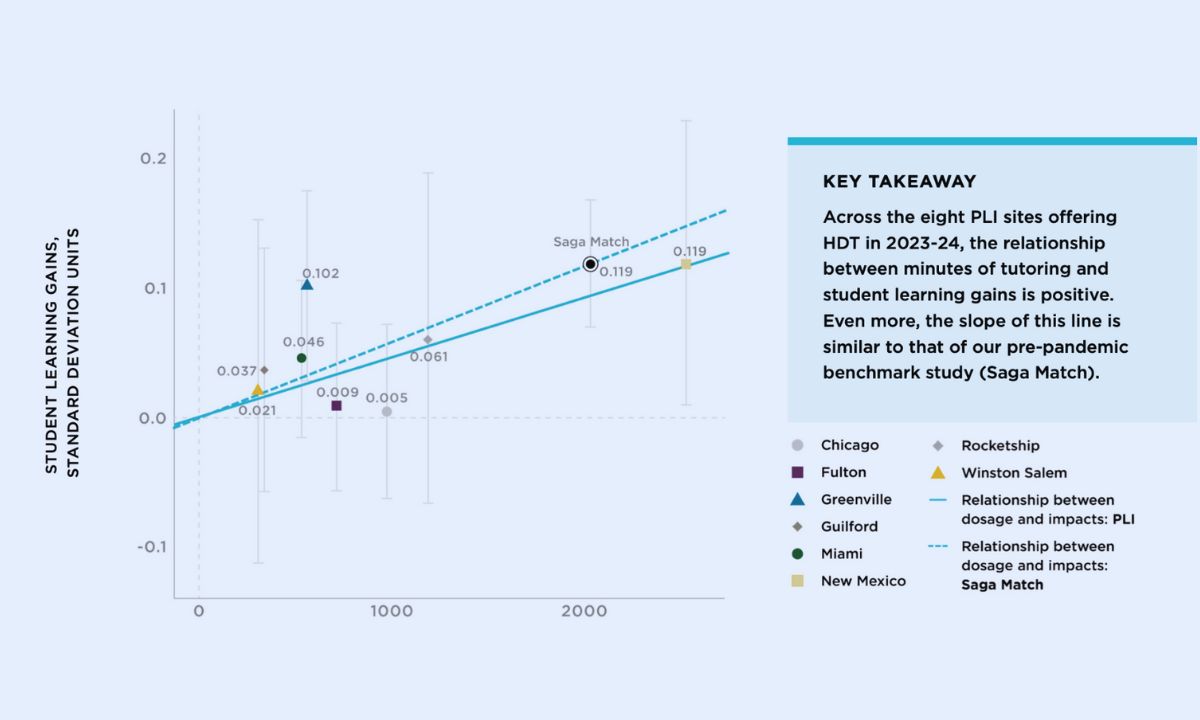

Recent findings from another tutoring study, the Personalized Learning Initiative, provides further proof that the more tutoring students receive, the greater their gains. But the “bad news,” according to the researchers, from the University of Chicago and MDRC, was that students often didn’t receive as much tutoring as originally planned.

“Conversations with the operators suggest schools felt they simply had too many competing demands on limited instructional time,” the authors wrote.

Recent research from the University of Chicago and MDRC reinforced the finding that the more tutoring students receive, the greater the learning gains. (University of Chicago/MDRC)

Recent research from the University of Chicago and MDRC reinforced the finding that the more tutoring students receive, the greater the learning gains. (University of Chicago/MDRC)

Another takeaway from the Stanford study is the “critical role” of relationships between tutors and students, said Rahul Kalita, co-founder of Tutored by Teachers, a virtual provider with a network of over 6,800 certified teachers. In the Indianapolis Public Schools, one of its largest clients, students are approaching pre-pandemic levels in reading, and nearly 70% of third graders passed a reading test this year required for promotion to fourth grade.

Without “consistent, human-to-human connection,” Kalita said, results will be similar to on-demand “edtech tools” that researchers have found to be ineffective.

‘Start with the curriculum’

Not only did Texas students not receive enough tutoring, the research team found a weak relationship between their sessions and the material they needed to know for tests. Tutors covered about a third of the math standards and only about half that in reading.

RelatedNew Research: Done Right, Virtual Tutoring Nearly Rivals In-Person Version

But this is an area where some tutoring companies have shown improvement, said Towns, with Accelerate. More successful providers, she said, “really start with the curriculum,” and hire experts with “deep knowledge around literacy or math.”

Multiple studies now show that remote tutoring can be just as effective as in-person programs. That’s why she encouraged districts not to give up on virtual models.

“Coming out of the pandemic,” she said, “everybody was just like, ‘Let’s try anything. Anything is better than nothing,’ and in fact that’s not true.”

Did you use this article in your work?

We’d love to hear how The 74’s reporting is helping educators, researchers, and policymakers. Tell us how