Every time we speak on the phone, my mother nearly blows my eardrum out with the force of her cough. Sometimes it’s a softer, throat-clearing rattle, but other days it’s an uncontrollable burst from her chest, followed by a laugh. I, however, don’t find it funny.

“Excuse me,” she repeats throughout the call. She believes her cough is the consequence of aging, but I remember when the hacks started.

We grew up on Texas’ Gulf Coast, one town away from a Dow petrochemical plant founded in the 1940s and proudly considered “the largest integrated chemical manufacturing complex in the Western Hemisphere.” I, like many of my Gulf Texas neighbors, know little about the chemicals produced inside the facility, but we know all too well that it is responsible for polluting our community’s air and water.

Growing up, much of my community worked at the plant and, as kids, we were warned to avoid swimming nearby. This didn’t stop us. We’d drive between industrial sites blasting music on our way to dip our toes in the sand. We weren’t bold or anything; we had just underestimated the severity of the situation. Even now, as I write and rewrite, there is a shelter-in-place order for current residents due to a chlorine gas leak. Such warnings are unfortunately part of everyday life in the Gulf.

At the end of high school, my immediate family eventually relocated about 50 miles north to join the rest of our relatives speckled around southern Houston. There was a unanimous agreement that the city had more to offer Black communities than our hometown did, even if the risks felt greater. So there we were again, comfortably nestled near new plants and tank farms in a new place.

A few years later, while I was attending college in New England, Hurricane Harvey barreled in, ravaging the Houston area, and leaving record damage in its wake. I remembered evacuating with my family for Hurricanes Rita and Ike in the 2000s, running into recently displaced evacuees from Hurricane Katrina during both. This time was just as serious, if not worse. My brother told a story of a boat floating past his second-floor apartment windows and the folks inside offering him a ride.

“How could it get that bad so fast?” My mother asked. “I don’t remember anything like this before.”

In grade school, I recall learning about the hole in the ozone layer, caused by pollution from harmful emissions. This lesson pushed me to make connections between the toxin-spewing plants near my hometown and the worsening environmental conditions. From a young age, I considered how the constant refining, tests, and accidents at the facilities billowed plumes of unspecified mixtures of smoke into the air, impacting my family and my community. I may not have known the true magnitude of the petroleum industry’s pollution on our health, but I did recognize that somehow each summer’s heat was even more unbearable than the last.

I tried not to be so bleak in my response.

“Global warming, I guess.”

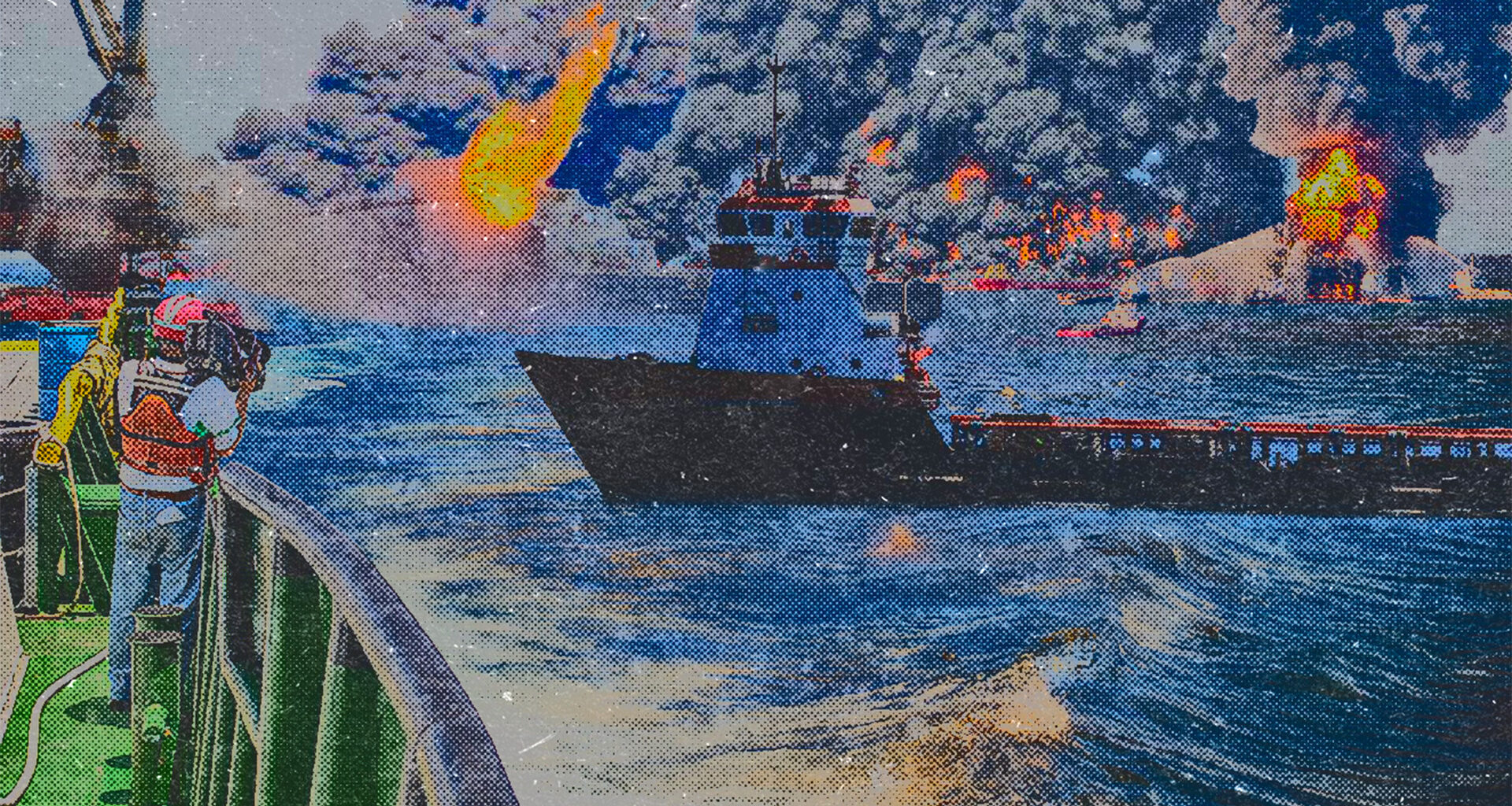

In March 2019, a massive chemical fire broke out at a tank farm owned by the Intercontinental Terminals Company (ITC) in metro-Houston’s Deer Park suburb. The fire destroyed multiple units containing toxic substances, spilling chemicals into the local water, and shooting ash into the air. For three days, toxic smoke filled Houston’s air with petrochemical gas, including benzene. Eyes and throats burned. Lungs struggled. Carcinogenic emissions lingered for weeks.

According to Environmental Health News, the Coalition to Prevent Chemical Disasters reports that Texas has more chemical emergencies than any other state. In 2023, the state had nearly 50 accidents, over half of which occurred in the Houston-Galveston area. Last fall, a hydrogen sulfide leak at the PEMEX Deer Park plant killed two workers while 30 others were treated for exposure to toxic chemicals. Before that, a natural gas pipeline owned by an energy company burned for four days after a car crashed into it. In each incident, there were few safeguards.

There is little difference between the 2019 event and recent ones. Negligence was to blame, per usual. In their investigative report on the ITC fire, the Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board (CBS) revealed that “the incident was linked to a number of safety shortcomings including the lack of an effective mechanical integrity program . . . as well as a lack of a formal process safety management program.” According to the report, the CBS warned ITC of its shortcomings and advised the company to fix them before the fire, but the company failed to do so. Perhaps they felt it was more cost efficient to just deal with the fallout in the event of an emergency.

With funding for every federal government entity being slashed by the Trump Administration, including a proposed 55 percent cut to the Environmental Protection Agency following last year’s 20 percent loss, there is little defense remaining for those who live in the dirtiest parts of the South. Prior to the second Trump election, many of Texas’ conservative legislators, who often live far away from the spills and explosions, worked hard to undermine the EPA in order to keep safety regulations loose and the state “business-friendly.” They look away and, in exchange, their pockets are lined and their campaigns robustly funded.

I, like many of my Gulf Texas neighbors, know little about the chemicals produced inside the facility, but we know all too well that it is responsible for polluting our community’s air and water.

My mother and a few of her siblings were among the thousands affected by the ITC fire and its aftermath. She developed a chronic cough and, as the years passed, she suffered multiple cases of pneumonia and bronchitis. Having worked for decades as a caregiver, she found herself struggling to catch her breath during regular tasks like lifting a client. With her conditions worsened by the subsequent COVID-19 pandemic, she was in and out of hospitals every few months. These frequent visits impacted her work schedule and often got her into trouble with her superiors.

Like many of the other victims, over the years, she lost work and gained new disabilities. Still, after raising a family as a single parent and failing to win the lottery, she was never rich, so she soldiered on through bouts of unemployment and denied disability claims. Eventually, she moved in with other family members, as her condition made it difficult to pay rent on her own.

We have kept one another afloat as best as we can. It has always been common for our family to send the same few hundred dollars back and forth between one another to survive, so without any other options, that’s what we did.

When you’re watching daytime programming, between sitcom reruns and game shows, men in personal injury commercials boast promises of high payouts and big settlements. I used to think that they were well-off scam artists and, it turns out, I wasn’t too far from the truth.

Typically, the “ambulance chasers,” also known as injury lawyers, on television focus on big rigs or class actions surrounding accidental cancer exposure, but in areas prone to environmental disasters, many are dedicated to exploiting those suffering from the incidents at the plants and chemical storage facilities. After the 2019 ITC fire, multiple firms descended on the thousands of victims immediately. Mom didn’t have to call them. They called her.

Months after the fire, she found herself in a room of her neighbors—many of them worse off than her—waiting to be medically evaluated. Families with young children, the elderly, and folks with pre-existing disabilities were also there hoping to have their hospital bills covered after surviving. My mom and her siblings were offered up to $17,000 in compensation for their injuries if they joined the civil suit being filed in their names and promised not to seek additional counsel. Having no up-front funds for a lawyer, and very little legal knowledge, they agreed to be represented.

It would take nearly five years for the firm to reach a settlement but it happened. ITC first paid millions to the state and, later, more to the private suits representing community members. We thought the date of the big payout would happen quickly, but my mom faced delays for an additional year due in part to fees and contracts. While she waited, mom called the law firm often to check on the status of the life-changing amount of money.

A few weeks ago, she called me, with joy in her voice. She let me know that the settlement was on its way and that she was driving to get the final documents notarized. We could finally pay off a few simmering hospital bills and maybe put a down payment toward a car she could own. Then a few hours passed and she called again, sounding defeated.

The allocation was much less than what was promised, around $8,000. After attorney’s fees, case expenses, and the cost of the medical evaluation, she would walk away with a measly $2,700. Some other family members got nearly $5,000, others as low as $900. It seemed they had misinterpreted the settlement offer; that they’d receive $17,000 total to be divided between the whole family, regardless of how each of them were personally affected. With everyone having signed the contract that required them to honor the result, they had no alternatives. That was it.

I was enraged, brimming with many questions. How many other families were duped in the same way? How much did the firm end up pocketing in “fees”? How many people had died from their conditions waiting for years on the payout? Was there any chance of challenging it? Did this happen all the time to locally impacted communities and this was simply our first experience with it?

I knew the answer to be the latter: yes. The levels of sickness in Houston’s Blackest and brownest wards are much higher in comparison to other parts of the city, as well as the rest of the state and the country. My family and their neighbors are simply collateral damage in the eyes of nearby polluters, and they are cash cows for the law firms that profit off of their suffering. While they lie dying, vultures wait on the sidelines to pick them clean.

At this point, I’m not sure which was dirtier: my mother’s life and that of many others being exploited to generate millions for the lawyers who offered to fight for their settlements, or the half-decade of worsening symptoms she endured while she waited for an anti-climatic outcome.

I haven’t lived in Houston for over a decade, city-hopping until I landed in Los Angeles a few years ago, so I rely on updates from my family between infrequent visits. Mom tells me that the Houston we grew up with is not the same as the Houston of today. There are gentrifiers in Third Ward, once the center of the city’s Black community, making it harder than ever to secure housing. Politically, the city government’s decision making is redder than the “purple” constituency, evident in the budget decisions and crackdowns on protests. The highways are packed every day, even heading south toward our old, podunk town. But the food’s still good.

For a while, I tried to entice her to move out near me. I knew she would hate the sudden inclines peppered around Californian roads but she’d love whale watching in the Pacific. She might miss the thick accents of her friends and family, but I was convinced she’d be better off in the West, for her own safety and maybe for a higher quality of life.

Then in January 2025, I was the one calling with my own cough from the local fires. Some were caused by arson and others, just like back home, by an energy company’s neglect. I sped away from my apartment one evening, watching the burning in my rearview mirror. The next day, I purchased an air purifier.

A few months later, I found myself on a date at Venice Beach where everyone clustered on the sand to dance and talk but almost no one swam or surfed. We all seemed to share the same unspoken knowledge. Even after all this time, there have been recent reports of dead animals, from seals to fish, washing ashore. Additionally, there have been warnings to avoid eating oysters, the ocean’s natural filters, as they are contaminated. The ash of the burnt homes and materials that lingered over Los Angeles before blowing out to sea had to come down eventually.

I’m honest with her now. I can pretend like I’m in a new paradise but it all reminds me of the same dangers we grew up alongside.

“Come back out this way,” she advised after a hack. “The air is much cleaner here.”