When Kaylie Mahoney Guerrero joined a TikTok trend in September 2019, she thought little of it.

The then-16-year-old scrolled past videos tagged with #FamousRelativeCheck and decided to share what, to her, felt like an ordinary truth: Her dad was a professional wrestler.

She filmed a short clip featuring a photo of herself as a young child with her father — World Wrestling Entertainment Hall of Famer and native El Pasoan Eddie Guerrero — adding the caption, “Does being the daughter of a WWE wrestler count?”

She posted it and went to bed. The next morning, her phone was flooded — more than a million views and a torrent of comments from fans throughout the world who couldn’t believe that the smiling teenager in their feed was the daughter of one of wrestling’s most beloved and tragic figures.

Eddie Guerrero holds his youngest daughter, Kaylie Mahoney Guerrero, whose recent visit to El Paso deepened her connection to the city her father helped put on the wrestling map. (Courtesy of Kaylie Mahoney Guerrero)

Eddie Guerrero holds his youngest daughter, Kaylie Mahoney Guerrero, whose recent visit to El Paso deepened her connection to the city her father helped put on the wrestling map. (Courtesy of Kaylie Mahoney Guerrero)

“I thought when I posted that maybe I would get, like, a thousand views or something from older guys that like wrestling,” Mahoney Guerrero, now 23, told El Paso Matters during a phone interview from her home in the Tampa, Florida, area. “Then, I woke up the next morning with 1.8 million views on it and so many people talking to me about my dad and sharing things I didn’t even know about my dad with me. I didn’t understand the magnitude of how much of an impact he made and how world-famous he actually was.”

That outpouring of love continues today in arenas large and small. It is part of what motivated District 3 city Rep. Deanna Maldonado-Rocha to take action. Earlier this year, she began creating a citywide day of recognition for the late superstar — a hometown son whose charisma and compassion made him a folk hero far beyond the squared circle.

On Tuesday, Nov. 18, El Paso will do just that. During their regular meeting, City Council members will proclaim Eddie Guerrero Day, inviting fans and residents to celebrate the legacy of the WWE icon who showed that greatness could be born in the Borderland — and that it could belong to everyone who believed.

“I grew up watching lucha libre here in El Paso. When Eddie made the stage, it was really cool to see representation for Latinos out there and the culture that he brought to it,” Maldonado-Rocha said. “He was representing El Paso. So, for me, it was almost like a full-circle moment to be able to say, ‘This is what I grew up on. This is important.’”

A hometown hero remembered

The effort to honor Eddie Guerrero began with Chris Rojas, an El Paso native who helps organize local wrestling events. A lifelong fan of Guerrero, Rojas contacted Maldonado-Rocha’s office earlier this year to explore ways the city might commemorate the 20th anniversary of Guerrero’s passing. Guerrero died of heart failure Nov. 15, 2005, in Minneapolis. He was 38.

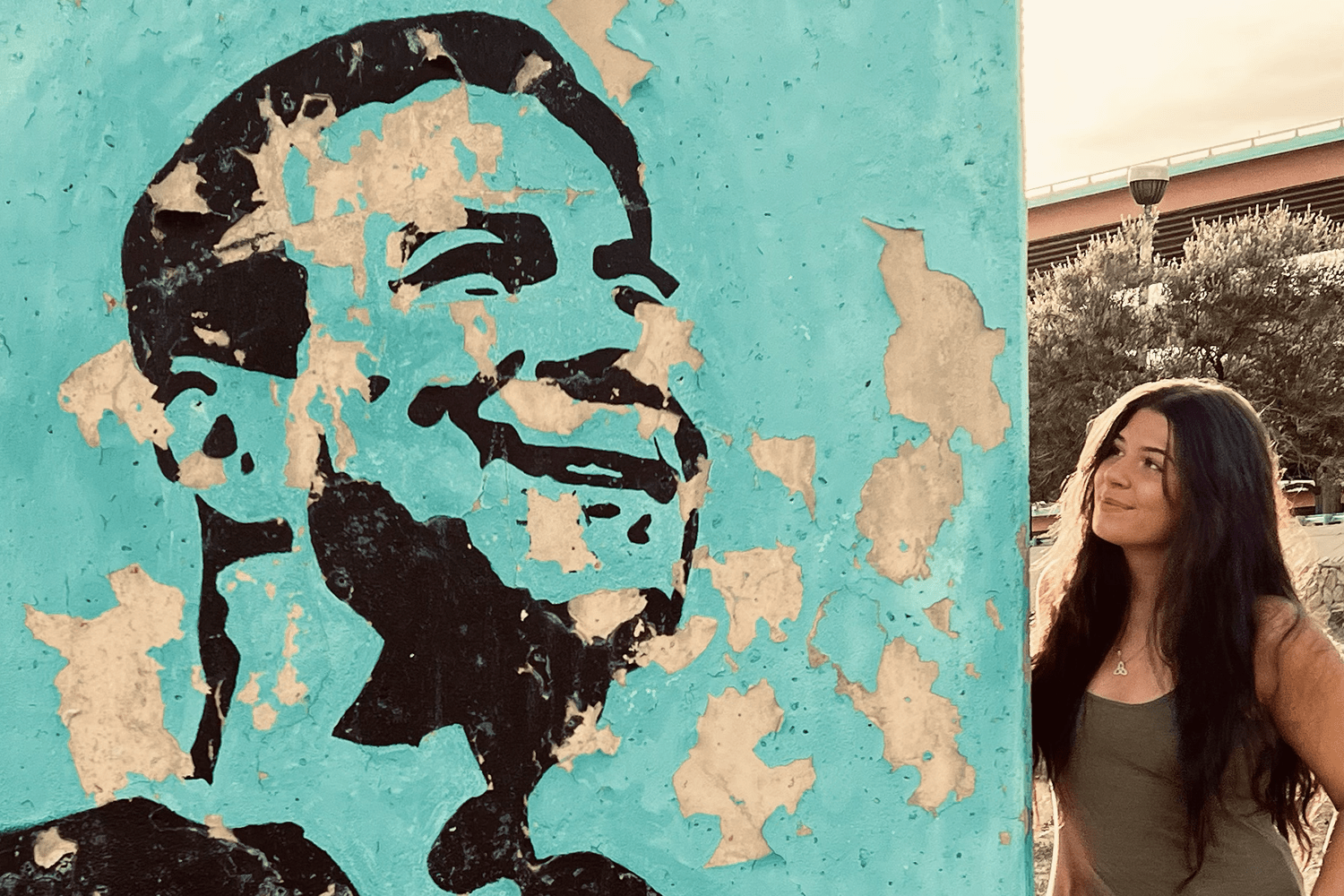

Kaylie Mahoney Guerrero, the youngest daughter of WWE Hall of Fame and El Paso native, Eddie Guerrero, stands next to a mural depicting her father in Lincoln Park in Central El Paso. (Courtey of Kaylie Mahoney Guerrero)

Kaylie Mahoney Guerrero, the youngest daughter of WWE Hall of Fame and El Paso native, Eddie Guerrero, stands next to a mural depicting her father in Lincoln Park in Central El Paso. (Courtey of Kaylie Mahoney Guerrero)

“They originally wanted to change the name of a recreation center or a street,” Maldonado-Rocha said. “And while my staff was working through that, I was, like, you know, one way we can do it is to do a proclamation.”

Maldonado-Rocha decided the tribute needed to be more than ceremonial.

“I want this to be really big, and I think he deserves it,” she said.

To that end, Maldonado-Rocha said the city will welcome some of Guerrero’s family members — including daughters Sherilyn Guerrero and Mahoney Guerrero — with a spirit of spectacle and community.

Organizers plan to park a trio of lowrider cars near City Hall along the 300 block of North Campbell Street — including one that once ferried Guerrero through El Paso — as fans gather for the proclamation ceremony.

Maldonado-Rocha’s office has invited residents to don luchador masks and bring their own wrestling memorabilia to honor the late champion, thus turning the memorial into a vibrant celebration worthy of Guerrero’s showmanship — part tribute, part fiesta and entirely El Paso.

Sherilyn Guerrero, daughter of Eddie and Vickie Guerrero, recently began her own journey into the wrestling world. On Oct. 30, the Reality of Wrestling school in Texas City, Texas — run by WWE Hall of Famer Booker T and Sharmell — announced that Sherilyn officially started her in-ring training with the company.

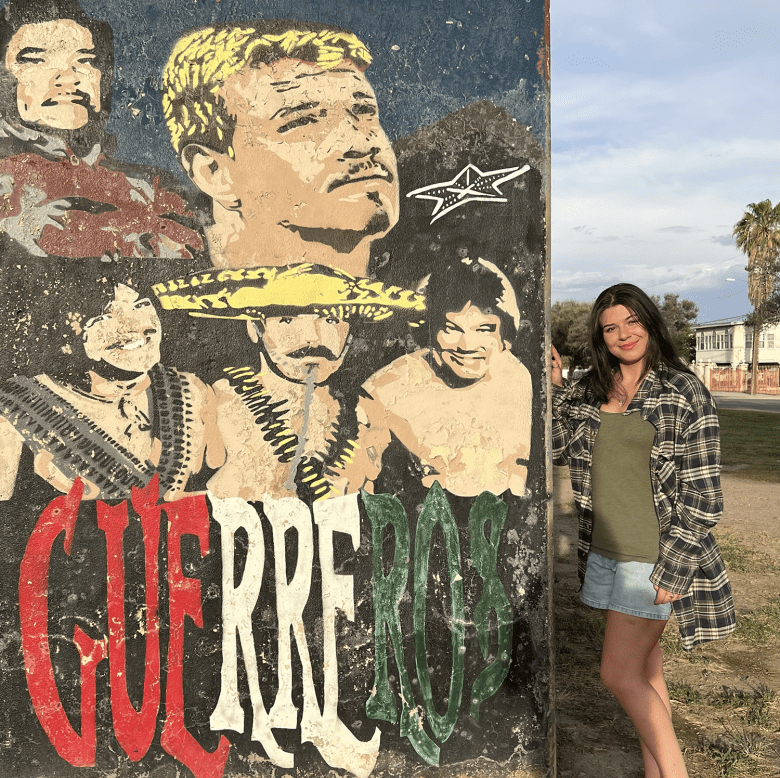

Rojas, for his part, remains involved in the celebration and is now helping lead a fundraising effort for additional community projects to honor Guerrero’s memory, including a new mural in Lincoln Park and a life-sized, bronze sculpture of the wrestling star that would be placed at a location to be determined.

Born Oct. 9, 1967, in El Paso, Eddie Guerrero grew up in a wrestling dynasty — the youngest son of Gory Guerrero, a pioneering luchador and promoter whose influence stretched from Ciudad Juárez to Texas arenas. Eddie trained on both sides of the border and attended Jefferson High School, where he began shaping the charisma and technical mastery that would define his career.

He rose through Lucha Libre AAA Worldwide in Mexico, and Extreme Championship Wrestling (ECW) and World Championship Wrestling (WCW) in the United States before joining the WWE in 2000, where his “Lie, Cheat and Steal” persona and fearless ring style made him one of wrestling’s most beloved figures. In 2004, he captured the WWE Championship, becoming a beacon of representation for Latino fans throughout the world.

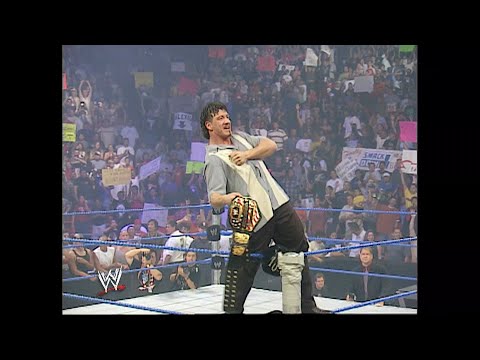

One of Guerrero’s most celebrated homecomings came a year earlier, on Aug. 28, 2003, during a “SmackDown!” show at the Don Haskins Center. Returning as the WWE United States Champion, he drove a sports car to the arena entrance, before descending to the ring where he exchanged words with a young John Cena, and subsequently pummeled him to the roar of thousands of El Paso fans — a moment still replayed online two decades later.

Maldonado-Rocha said that energy — that sense of pride and representation — is what she hopes to capture at City Hall. She added that her office will continue to assist other efforts to honor Guerrero where possible.

“When he was on stage, you know, in the ring, he really represented being a Chicano,” she said. “He broke boundaries for himself. More than anything, I think Eddie had a huge corazón. I think he wore that on his sleeve.”

Guerrero’s career was not without struggle. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, he battled substance-use issues that nearly cost him his marriage, his relationship with his daughters and the career he had built since childhood. He was involved in multiple DUI incidents, entered and left rehabilitation programs, and was eventually released from WWE as he attempted to address a cycle of alcohol and prescription drug misuse that had followed him through his years in WCW and into his early tenure with WWE.

But Guerrero’s story was also one of redemption. After leaving WWE, he spent more than a year rebuilding his life — returning to independent wrestling, recommitting to sobriety and repairing his family relationships. By the time he rejoined the company in 2002, those close to him described him as a man determined to stay clean, both for his health and for his children. His 2004 WWE Championship win against Brock Lesnar became a milestone not only in his career but in his recovery: a moment he openly framed as evidence that he had reclaimed his life. When Guerrero died the following year, he was widely reported to have been sober.

The Eddie Guerrero mural in Lincoln Park, originally created by Eric Dubitsky in 2007, honors the El Paso-born luchador and other members of the Guerrero family, Nov. 14, 2025. (Corrie Boudreaux/El Paso Matters)

The Eddie Guerrero mural in Lincoln Park, originally created by Eric Dubitsky in 2007, honors the El Paso-born luchador and other members of the Guerrero family, Nov. 14, 2025. (Corrie Boudreaux/El Paso Matters)

‘Eddie! Eddie! Eddie’

Two decades after Eddie Guerrero’s death, his name still brings crowds to their feet.

That enduring presence was on full display Nov. 3 during a WWE “Raw” show in Rio Rancho, New Mexico. That night, Dominik Mysterio stepped into the ring to exchange words with his father, Rey Mysterio.

The real-life father and son have feuded in the ring on and off for years, but that night Dominik revisited a storyline first told two decades earlier, one in which Guerrero and Rey battled for guardianship of the then-8-year-old Dominik. The saga, which also involved questions about Dominik’s paternity, concluded at SummerSlam 2005 when Rey bested Guerrero in a ladder match.

During their most recent in-ring encounter in New Mexico, Dominik bristled at Rey’s suggestion that he wasn’t the WWE’s best luchador. Rey asked his son to consider his assertion while rattling off the names of previous Latino wrestling greats including Eddie Guerrero. The crowd responded instantly, the chant swelling from the front rows and rippling through the arena:

“Eddie! Eddie! Eddie!”

It was the same refrain that shook buildings throughout Guerrero’s career.

In a letter published Thursday in The Players’ Tribune — marking 20 years since Guerrero’s death — Rey Mysterio reflected on that same “Raw” moment. In the publication that features first-person stories from professional athletes, Mysterio wrote that the eruption that followed the mention of Guerrero’s name “took (his) breath away.” He described the chant as a reminder of how alive Guerrero’s presence remains in arenas.

Earlier this year, Dominik paid an even more personal tribute. In June, he visited Guerrero’s gravesite in Scottsdale, Arizona, where Guerrero was living at the time of his death.

In a social media post, Dominik shared a photo of the WWE Intercontinental Championship belt he won at Wrestlemania 41 laying on the headstone. It was a quiet, symbolic fulfillment of a promise he had made years earlier — that if he ever became champion, he would dedicate it to the man he still calls his inspiration.

Moments like these keep Guerrero’s legacy alive for a new generation of fans. For his youngest daughter, Kaylie Mahoney Guerrero, that steadfast love has become a constant reminder of how her father’s life extended beyond the ring.

“The most heartwarming thing I’ve heard from fans is, ‘Your father made me feel proud to be Mexican,’” she said. “To know my dad led by example and encouraged other Latinos to follow their dreams is incredibly heartwarming.”

The Borderland’s wrestling roots

Whether in a packed arena or an online thread thousands of miles from El Paso, Eddie Guerrero’s name still carries the same power it did when he stood atop the turnbuckle. And it paved the way for others.

One of them is Cinta de Oro. For Cinta, lucha libre isn’t just a sport. It’s a language that El Paso helped write. He spent his childhood moving through the city’s Segundo Barrio and East-Central neighborhoods, attending schools including Alamo Elementary School, Ross Middle School and eventually Burges High School, where he first encountered the sports that would change his life, even if it looked a bit different than he expected.

El Paso luchador Cinta de Oro greets fans during the lucha libre event he organized at Ascarate Park, Sept. 6, 2025. (Corrie Boudreaux/El Paso Matters)

El Paso luchador Cinta de Oro greets fans during the lucha libre event he organized at Ascarate Park, Sept. 6, 2025. (Corrie Boudreaux/El Paso Matters)

“My idea of wrestling was in the wrestling ring that you see on TV,” said Cinta, who asked that his real name not be used in adherence with the masked luchador tradition of anonymity. “It wasn’t what I saw at Burges. This was a circle. You get on the mat. I was, like, ‘What am I getting myself into?’ But for me, when I was a young kid, my goal was to become a professional wrestler. I used to go to watch lucha libre as a young kid, and I remember asking, ‘What do I gotta do to get into wrestling?’ And I would hear, ‘You’ve got to do amateur wrestling.’ But I didn’t really know or understand what that was.”

He figured it out in quick fashion. Cinta qualified for the Texas state wrestling tournament in 1995. In 1996, he won the state championship in the 135-pound division. He parlayed that into a brief college wrestling career at Western New England College in Springfield, Massachusetts, before returning home where he transitioned into the realm of lucha.

That chase carried him from El Paso’s wrestling mats to arenas throughout Mexico and the United States, before eventually landing a spot on the WWE roster from 2011 to 2019, where he wrestled as the masked Sin Cara and the unmasked Hunico.

While being part of the country’s premier wrestling organization was momentous, Cinta believes the border has always been the true center of the wrestling world.

“I try to study a lot of it because this is what I love, this is what I do,” he said. “El Paso is a very important city for the world of lucha libre. We have a lot of history here in El Paso, a lot of wrestlers that have been famous … Eddie Guerrero, obviously.”

Luchadores laugh and groan as they perform wall squats during a lucha libre class at the Boys and Girls Club in Segundo Barrio, Sept. 3, 2025. (Corrie Boudreaux/El Paso Matters)

Luchadores laugh and groan as they perform wall squats during a lucha libre class at the Boys and Girls Club in Segundo Barrio, Sept. 3, 2025. (Corrie Boudreaux/El Paso Matters)

That history still shapes the culture he’s now helping sustain. In Segundo Barrio, he recently opened the Cinta de Oro School of Lucha.

Classes take place during the week at the Boys and Girls Clubs of El Paso in Segundo Barrio, a place Cinta De Oro used to frequent when he was a child. Students train not only in holds and suplexes but in the storytelling and discipline that have defined border wrestling for generations. The mask, he said, remains central to that identity.

“When I’m the normal person, it’s way different than when I am the guy that wears a mask,” Cinta said. “I think I feel like it’s a protection, like it’s an alter ego. When we put the mask on, it’s like this completely different person, personality, the way we express ourselves. And you’ve got to connect with people. You have to have that charisma, you have to be able to get out of your shell. You’ve got to get out of the box, you know?”

Through that simple act — stepping into the ring and pulling the mask over his face — Cinta de Oro continues a tradition that links generations of Borderland wrestlers. The crowd’s roar, the color, the bravado — all of it, he said, is part of something older and larger than any one performer.

A small Cinta de Oro fan waits for the start of a lucha libre event at Ascarate Park, Sept. 6, 2025. (Corrie Boudreaux/El Paso Matters)

A small Cinta de Oro fan waits for the start of a lucha libre event at Ascarate Park, Sept. 6, 2025. (Corrie Boudreaux/El Paso Matters)

Art, masks and modern expression

If lucha libre began as a sport, it endures as a language — a vocabulary of movement, costume and identity that continues to shape El Paso’s creative life.

For artist Alejandro Macias, the luchador’s mask has always been more than an accessory. It is a visual metaphor that travels across borders, cultures and personal histories. That sensibility is woven through his work, including “Nopal en la Frente (con Bud Light),” a painting that now hangs in the permanent collection of the El Paso Museum of Art.

“I was always interested in masks, even as a young child,” said Macias, an assistant professor of painting and drawing at the University of Arizona School of Art. “I would have masks of luchadores when I was a kid. As soon as you take on this alter ego and this other persona, everything changes. You can be someone else, you can be whoever you want.”

For Macias, a Brownsville, Texas, native, the mask reflects a familiar tension for border residents — a blending of identities, a shifting of selves, a daily negotiation of how one is seen.

“I think sometimes people need (masks) as a way to feel empowered, because there is maybe an aspect of your own existence that is perhaps a little vulnerable,” he said. “You can use the mask as a way to conceal that. It would also, in many ways, parallel to code-switching … as a form of assimilation, as a way of survival.”

For Marty Snow, 24, who was born in El Paso and raised in Juárez, that same interplay between disguise and truth unfolds under venue lights.

“My uncle was the one who introduced us to ‘SmackDown!’ And after that, it was just kind of like love at first sight,” he said.

Local wrestler Marty Snow of Delgado Promotions grew up moving between El Paso and Juárez, and says lucha libre’s blend of performance and identity has guided his path in the ring. (Courtesy of Marty Snow)

Local wrestler Marty Snow of Delgado Promotions grew up moving between El Paso and Juárez, and says lucha libre’s blend of performance and identity has guided his path in the ring. (Courtesy of Marty Snow)

His first major foray into masks wasn’t by choice. Snow graduated from Cathedral High School in 2020 during the COVID pandemic. He laments that he didn’t get a traditional graduation, instead receiving his diploma with a mask secured on his face and a pantomimed handshake. A year later, he joined Delgado Promotions, a professional wrestling organization headquartered in Central El Paso.

Every Friday, Snow joins names such as Aydan Colt and El Cobarde to delight local wrestling fans. Inside the ropes, Snow discovered that the mask wasn’t a prop — it was a portal. It allowed him to tell a story that resonated with people.

That story involves not just physical feats of strength, but an ability to play a character.

“I think it’s always really important to kind of try to be good at both things because that’s what the best wrestlers have been able to do,” Snow said. “You look at Eddie Guerrero. He was a really great wrestler, but if you see his promos, his skits, they were also very entertaining.”

The borderland has long produced performers whose work blurs the line between wrestling and art.

One recent example is Saúl Armendáriz, better known as Cassandro el Exótico, the El Paso-born luchador whose flamboyant costumes, expressive makeup and emotional storytelling transformed the exótico style in Mexico. His life — depicted in a 2023 biopic starring Gael García Bernal and celebrated through local murals and museum exhibits — reflects how lucha libre has served as a stage for identity, resilience and creative expression throughout the region.

A legacy that lives everywhere

When El Paso gathers this week to proclaim Eddie Guerrero Day, the celebration will bring together fans, family and generations of wrestlers who still feel his influence.

For city Rep. Maldonado-Rocha, Guerrero’s story embodies the city’s spirit.

“He broke boundaries, and I feel like El Paso, we have a lot of people, we have a lot of organizations that really break boundaries in their own industries,” Maldonado-Rocha said. “But he broke boundaries for himself, being a Latino in something that was predominantly … there were no Latinos in there. Eddie had a huge heart”

That heart still beats through the city’s wrestling culture.

For Kaylie Mahoney Guerrero, visiting El Paso earlier this year reminded her that the connection between her father and his hometown remains strong. She returned in March for a Total Nonstop Action (TNA) Impact Wrestling event at the El Paso County Coliseum, where her cousin and one-time Eddie Guerrero tag-team partner, Chavo Guerrero Jr., performed before a packed crowd.

Chavo Guerrero announced in September that he signed a new deal with the WWE.

Kaylie Mahoney Guerrero poses with her cousin Chavo Guerrero Jr. before he wrestled in a TNA “Impact!” event in March 2025 at the El Paso County Coliseum. (Courtesy of Kaylie Mahoney Guerrero)

Kaylie Mahoney Guerrero poses with her cousin Chavo Guerrero Jr. before he wrestled in a TNA “Impact!” event in March 2025 at the El Paso County Coliseum. (Courtesy of Kaylie Mahoney Guerrero)

“This was especially memorable because they have a beautiful mural of my father there,” Mahoney Guerrero said. “Not only that, but I learned my father and his family members would run around the Coliseum while my grandfather, Gory, worked upstairs when they were children.”

She also visited Lincoln Park to see the murals painted by Eric Dubitsky, depicting her father, Los Guerreros and her sisters.

“I’m truly proud to say my father came from such an amazing community,” she said. “Words will never describe how thankful I am that they continue to honor him.”

Make Plans

What: Eddie Guerrero Day proclamation at El Paso City Council meeting.

When: 9 a.m. Tuesday, Nov. 18.

Where: City Hall, 300 N. Campbell St.

Of note: Fans are encouraged to wear luchador masks or wrestling apparel to take part in the celebration.

Watch: Livestream available on city of El Paso YouTube page.

Related

LISTEN: EL PASO MATTERS PODCAST