There’s just something about the sea. Maybe it’s the waves, or it’s the mystery, or the infinitude of it all, that’s stuck to the minds of so many quintessential artists. Think of Herman Melville, of course. Or his French contemporary, Jules Verne. New England painter Winslow Homer fell victim, too. So did James Cameron.

For Ethan Rutherford, it all began at the Puget Sound, the vast natural estuary that connects Seattle to the Pacific Ocean, where his father would take him sailing as a child. Perhaps it was right there on those boats, or years into his career as an author, where he, too, drew inspiration from the eternal muse.

“If you look at the sea,” Rutherford says. “It’s this unlimited, unbounded space. But a ship is a vessel. You have this narrative cafe where the action is occurring, so it’s like you have two spaces at once. You have a limitless space, and you can’t see the depths. But then on the boat itself, your characters can only stray so far.”

His latest book, North Sun, was released earlier this year and is the final product of an idea that came to him more than 10 years ago. The story takes place almost entirely on the hull of the Esther, an American whaler ship on a grueling expedition from New Bedford, Massachusetts, to the Chukchi Sea, in which Captain Arnold Lovejoy is to deliver a mysterious letter, and his crew is ordered to capture as many whales as they can along the way.

When news happens, Dallas Observer is there —

Your support strengthens our coverage.

We’re aiming to raise $30,000 by December 31, so we can continue covering what matters most to you. If the Dallas Observer matters to you, please take action and contribute today, so when news happens, our reporters can be there.

Ethan Rutherford’s new novel, North Sun, is up for one of the biggest awards in American literature.

Ethan Rutherford’s new novel, North Sun, is up for one of the biggest awards in American literature.

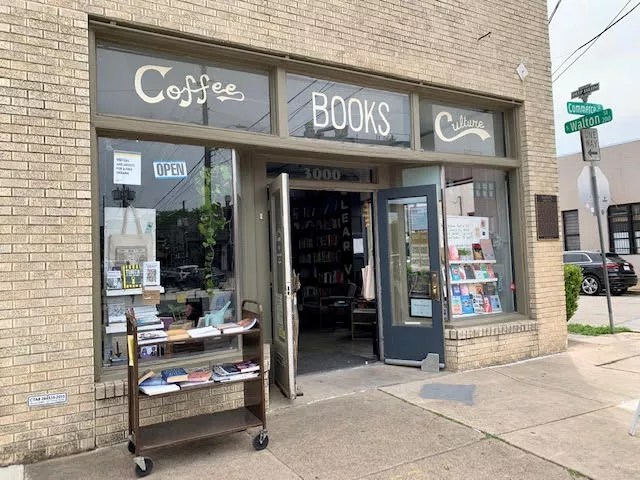

Released under Deep Vellum, Dallas’ literary epicenter, the book has been listed as one of 25 finalists for the National Book Award for Fiction, the most prestigious prize for American literature.

“It was total shock,” Rutherford says of his reaction to the news. “I don’t think it has settled in. It’s like walking around in someone else’s dream.”

Given the news, we decided to walk around in Rutherford’s dream, if only for a couple of nights, and read through North Sun ahead of a conversation with him about it.

The first thing you notice while reading North Sun is not its ensemble framework, which shifts perspectives between Captain Lovejoy, his crew, a wealthy family sponsoring the mission and two young boys trapped in the bowels of the Esther. It’s also not the book’s hyperreal depiction of late 1800s seafaring, or the all-too-real parallels drawn from the crew’s brutal whaling techniques to 21st-century environmental destruction. It’s not even Old Sorrell, the novel’s nightmarish creature, which has the head of a bird and the body of a man.

Instead, the first thing you notice while reading North Sun is its structure.

The novel is arranged in short blocks of text, sometimes only a paragraph or two per page, that each read as their own standalone piece of action. It’s a story told through hundreds of seemingly disconnected moments that, over time, begin to take shape as one sprawling composition, not dissimilar from waves in the sea.

“It feels like waves hitting the hull in this sort of repetitive motion,” Rutherford says. “It made me feel like I was in the boat while I was writing it.”

He got the idea from a piece in the Paris Review with author Don DeLillo, who posited a writing process where each paragraph is typed on an open page by itself, in order to isolate each word and see what comes to life.

Early in the writing process for North Sun, Rutherford gave the process a try, breaking up his narrative into smaller pieces until it began to feel “rhythmic” and “musical,” as he put it.

Though never formally in the book, music flows throughout North Sun. Rutherford mentioned David Bowie’s rendition of the Peter and the Wolf symphony numerous times in our conversation. The piece, originally written in 1936 by Russian composer Sergei Prokofiev, tells a traditional children’s fairy tale, utilizing specific instruments as audio motifs to represent different characters and actions.

To Rutherford, this framework is what makes North Sun’s ensemble narrative cohesive, using each character and disconnected vignette like a specific instrument, each humming the right notes at the right time and culminating in one massive symphony.

“One instrument comes on and sings for a while,” Rutherford says. “And then another instrument comes on and has the stage. That was part of the design of the book for me. It is an ensemble piece, and the camera can move and rove. It sort of belongs to nobody, but the heart, for me, is definitely the boys.”

Amidst all the brutality of the whaling expedition and the demons that haunt the crew carrying it out, two young, nameless boys are trying to find their place on the Esther and the world at large.

“As soon as I started following the boys around, I started to realize that no matter what kind of brutality is happening, these two can’t be separated,” Rutherford says. “They had this sort of tenderness between them, even though they undergo all this stuff. That was the breakthrough. The book doesn’t belong to the captain; it doesn’t belong to this weird bird-headed god of the sea. It’s a book about these two brothers.”

But Old Sorrell, that weird bird-headed god of the sea — Rutherford’s creation pulled from an amalgamation of sailor folklore — floats through the book like a ghost. Though frightening at first sight, the creature befriends the two young boys and starts to protect them in times of danger.

“I wanted him to be a little bit frightening and a little bit unreliable,” Rutherford says. “But also a deep comfort for the boys when he appeared. I saw him as an expression of my own helplessness as a writer. When you’re writing these scenes of slaughter and destruction with these characters that you deeply care about. You just go, isn’t anybody going to help these characters? To some degree, Old Sorrel became my version of trying to interrupt this, imaginatively.”

Within the context of the story, Old Sorrel’s presence starts to feel like a harbinger for change, whether the change is for the best or the worst. It’s as if the bird-man is Rutherford’s own vessel for moving the story along.

Whether it’s via his literary vessel or in the literal vessel that his characters inhabit, the trappings of Rutherford’s novel all boil down to the same thing: movement. It’s not the destination, it’s the journey, as people say. However, Rutherford operates from the perspective that the destination is the journey itself.

There’s a quote, a little over halfway through North Sun: “The wind might howl, but we won’t listen,” it reads. And it’s the summation for every character involved, that no matter the stakes, the circumstances, the mounting reasons to not keep moving, you simply must, even if you have no idea what lies ahead. In North Sun, it’s the danger of life at sea, as Rutherford’s characters battle the environment, their instincts and each other.

It’s hard not to draw parallels between those dangers and the all-too-real anxieties of a writer, or any artist, toiling away in their own imagination, unsure of what lies ahead. Are you creating something good? Will anyone ever see it? If they do, will they care?

Rutherford, or the eternal artist, cannot consider these things. Food molds when it settles. Muscles weaken without use. People die after they retire. The next time you hear the wind howl, don’t listen.

“It feels like you’re on the ice and you’re trudging by yourself,” Rutherford says. “You’re just going one foot in front of the other, and the only thing you know is that you just can’t stop.”

The National Book Award winners will be announced in a live ceremony on Wednesday, Nov. 19.