When Dallas Area Rapid Transit’s first Silver Line train rolled out of the Shiloh Road station in Plano at the end of October, it ushered in a new era for rail travel in Texas. Confetti was released as the train burst through a commemorative banner, live music played, and free rides were given to the train’s first-ever commuters.

First proposed in the 1980s, DART’s 26-mile line runs from Plano to DFW Airport, connecting Plano, Richardson, Dallas, Addison, Carrollton, Coppell and Grapevine, and the University of Texas at Dallas along the way. DART had pitched the long-awaited train as a new tool for North Texas commuters as well as an investment in the region, one of the fastest growing places anywhere in the country.

“This project connects neighborhoods, employers, and the world’s third-busiest airport in one seamless ride,” Nadine Lee, DART president and CEO, said in a release at the time. “It’s a catalyst for economic growth and a step toward a more connected North Texas.”

DART’s new train seemed like cause for celebration. In Texas, where the automobile is king and highways are our fiefdoms, the opening of a new train line that actually takes people where they want to go is about as rare as the birth of Christ. But not even a week after the Silver Line opened, Plano decided it had seen enough, and its city council voted to hold an election next spring to allow voters to decide whether Plano should leave DART entirely. Plano joined the nearby suburbs of Highland Park and Farmers Branch in doing so. Two days after Plano’s decision to hold an election, Irving followed suit.

If, in the spring, voters in the four suburban cities do decide to vote to leave DART, the fragile compact that sustains the state’s largest public transit agency could be torn to shreds, leading to immediate service cuts, abandoned train stations, and lots of delays.

Long train runnin’

Created in 1983, DART works like this: The agency’s 13 member cities fund the agency through sales taxes. Each city collects two cents on every dollar spent in its limits, and gives one of them to DART. The system is governed by a board of 15 members, with board membership proportionate to member cities’ population. Dallas, the largest member city, gets eight seats on the board, while the remaining members appoint the other seven.

Since its inception, this framework has kept the trains in North Texas (mostly) running on time. Suburbs pay into DART, and in return they get buses, paratransit services, and trains, depending on the service area. But the system has always rested on shaky ground.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, suburban member cities voted to leave DART over a myriad of concerns, from complaints about the funding scheme to the board structure to the services rendered. Voters in Flower Mound and Coppell successfully left the system in 1989. This will be the third time Farmer’s Branch has asked voters to leave DART after doing so in 1985 and again in 1989. And Plano tried to jump ship in 1989 and 1996. Each time, voters decided to remain in the compact.

This legislative session, North Texas representative Matt Shaheen and State Sen. Angelo Paxton filed bills that would have limited how much DART can raise in taxes. Plano, Irving, and Highland Park backed the bills, which DART said would have “crippled” the agency. But they died before the session’s end.

Night photo of a Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART) train stopped at a station in downtown Dallas. (HUM Images/HUM Images/Universal Images Grou)

So with no help from Republicans in Austin, the burbs turned to withdrawal votes. One point of contention this time around is the domination by the city of Dallas. Plano leaders have indicated that they want to see what they say is more equitable representation on DART’s board.

“Right now, one city essentially holds the majority of control over how services are allocated to everyone else,” Plano City Council member Julie Holmer said at a meeting earlier this month. “That just doesn’t make sense for a regional system that’s supposed to serve all of us.”

DART critics have also wielded the usual complaints about public transit: that it brings crime, that it’s underutilized and too expensive for what it provides, and that cities should instead pivot to microtransit and rideshare services.

The rebel cities have also argued that they give DART more than they get out of it. Suburbs have brandished a 2024 report, done by an outside consulting firm, that showed that many member cities pay into the system more than they receive in return. For instance, in 2023, Plano paid $109 million into DART, but DART only spent $44 million in the city. Farmers Branch paid $24 million into the system to get about $20 million back.

“Certain cities, Plano being chief amongst them, are heavily subsidizing the DART system,” former Plano council member Shelby Williams told the Dallas Morning News.

Irving actually got more money back than it paid into DART in 2023. That didn’t change their calculus.

“The whole concept was ill-concieved,” Irving Deputy Mayor Pro Tem Mark Cronentwett said about DART’s structure as the city council voted for the exit vote. “It’s obviously created this disparity where cities like Arlington or Frisco use that 1% for economic development, creating sports venues in particular, where you would think there’ll be a great interest in having mass transit to them, but there isn’t, because they’re not in DART.”

DART leaders criticized that report, saying it didn’t take into account the value of the Silver Line, which had yet to open. And DART leaders have said that while they are willing to listen to the concerns of the system’s members, investment in member cities is based on need, not necessarily proportion of money spent.

“I understand that a lot of people want sort of a dollar in and dollar out,” Lee, the DART CEO, said at a press conference last month. “But that’s just not the way things work.”

End of the line?

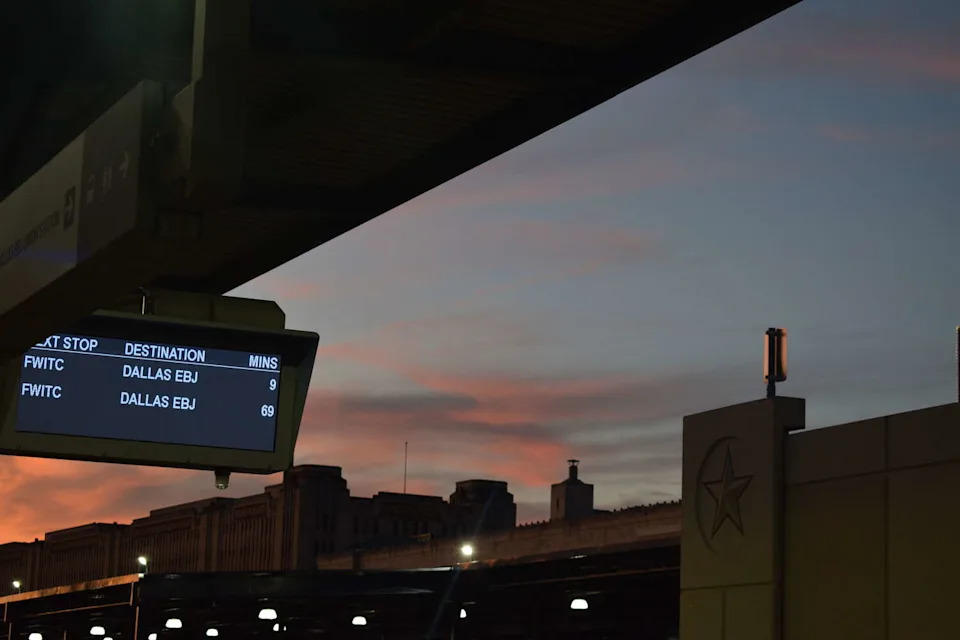

A Trinity Railway Express station in Fort Worth at sunset on Nov. 15, 2025. If suburban cities vote to leave DART, it could impact TRE service, which serves commuters throughout the region. (Gwen Howerton/Chron.com)

Absent from many of the discussions about sales taxes and returns on investment and board membership allocation is a glaring question: If the four dissident suburbs leave DART, what happens to service? And what replaces it?

DART hasn’t been coy about what exits would mean for the rebel cities. If voters do decide to leave the system, DART services would shut off as soon as the day after the vote. That shiny Silver Line train, the one that DART just built? It would no longer make a stop in Plano. Paratransit riders across DART’s 700-mile service area could see delays and cancelled rides. The Trinity Railway Express, a commuter rail that runs from Fort Worth to Dallas, would speed right through its stops in Irving. Jeamy Molina, DART’s Chief Communications Officer, told Chron that a “worst case scenario” where all four cities leave would have a massive impact on not just local transit users, but commuters across the region.

“Most of our riders aren’t just intra-city but regionally, right? Riders are going from Dallas to Plano, or from Irving to Farmers Branch and Carrollton and Plano,” Molina said. “[DART withdrawals] would have a huge impact on what that looks like.”

Lee, the DART CEO, has raised the alarm about what it would mean for riders across the whole system.

“If any city withdraws from DART, obviously there is a financial impact to DART as a whole,@ Lee said at a press conference. “We would be very concerned about the impacts it would have across our entire network of services. … The riders will be impacted by any action that a city takes.”

So if the rebel cities cut ties with DART, what replaces their public transit? Plano and Irving have announced their intentions to fund “microtransit” services, which are typically on-demand ride-share shuttles. The City of Houston already runs a similar service downtown, though skeptics have questioned if the service is worth its price tag. Plano said in a news release last month that regardless of how the DART vote goes, it sees microtransit as its future, though it has put forth a deal that could keep it in DART after all.

“Funding is already set aside to implement a fast, efficient Microtransit solution tailored to the community’s needs,” the release said.

Curiously, Plano had a microtransit scandal of its own earlier this year. Paul Wageman, the former DART board chair who represented the city on the board, resigned earlier this year. Wageman had been one of the loudest voices in Plano for reducing bus and light rail services in favor of microtransit services. At the same time, Wageman was an attorney for a business law firm and was registered as a lobbyist for Uber. While Wageman, Plano, DART, and Uber all said that everything was above board, that relationship didn’t sit well with some residents, who called Wageman’s background “fishy” at a Plano city council meeting in January. The Dallas Morning News reported that Plano city manager Mark Israelson attended a presentation on microtransit from Uber earlier this month.

Arlington, for years one of the largest cities in America without public transit, runs a microtransit service called Via in partnership with company Via Transportation since 2017. But while it has seen success, it may not be up to the task of serving commuters in North Texas. Alex Flores, a public transit user in Plano, told the Dallas Morning News that Via is too small to replace what DART provides.

“It’s just so much demand for a small system and it becomes very apparent that it is not enough to support the amount of people that need the service,” Flores told the newspaper.

That demand will only grow. North Texas is growing rapidly, and even the Texas Department of Transportation, which focuses most of its budget on highway maintenance, said earlier this month that Texas needs more public transit. Will voters agree? Only time will tell.

More Culture

Merch | H-E-B’s latest t-shirt collab was a disaster

Drama | Houston billboard lawyer ousts partner, adds new one with similar name

Super Bowl | Petition calls for Texas country icon to take halftime show

History | This 1995 flick almost derailed Matthew McConaughey’s career

For the latest and best from Chron, sign up for our daily newsletter here.

This article originally published at A suburban revolt might tear Texas’ largest public transit system apart.