The man was far from his former life when Dallas Area Rapid Transit police encountered him at a bus station on Bryan Street.

Once an airline employee, he developed a drinking problem and was now living on the streets, a DART spokesperson said.

Instead of bringing him to the overcrowded Dallas County jail on a criminal trespass charge, police had another option.

Police brought him to the Austin Street Center shelter near downtown, where a new transition center is helping homeless clients suspected of misdemeanor criminal trespass get stabilization services instead of criminal charges.

Crime in The News

Since the eight-beds launched in mid-October, it has connected people with mental health services, trauma support or family members instead of incarceration through a partnership with the district attorney’s office and funding from the North Texas Behavioral Health Authority.

Although the pilot program is starting small, county officials hope the center can be expanded here and replicated across the county to reduce the jail population and keep it from serving as de facto mental health treatment facilities.

County Commissioner Andrew Sommerman said officials are exploring creating four deflection centers across Dallas County, including expanding the Austin Street transition center, within the next year.

When DART brought the man to the center from the Bryan Street bus station, Austin Street’s director of housing coordinator Valerie Palmer said Austin Street and DART police helped connect him with his mother so he could start anew.

District Attorney John Creuzot said it’s part of an effort to bring lasting change to people who are arrested repeatedly on the same low level charge who are not receiving help they need in jail.

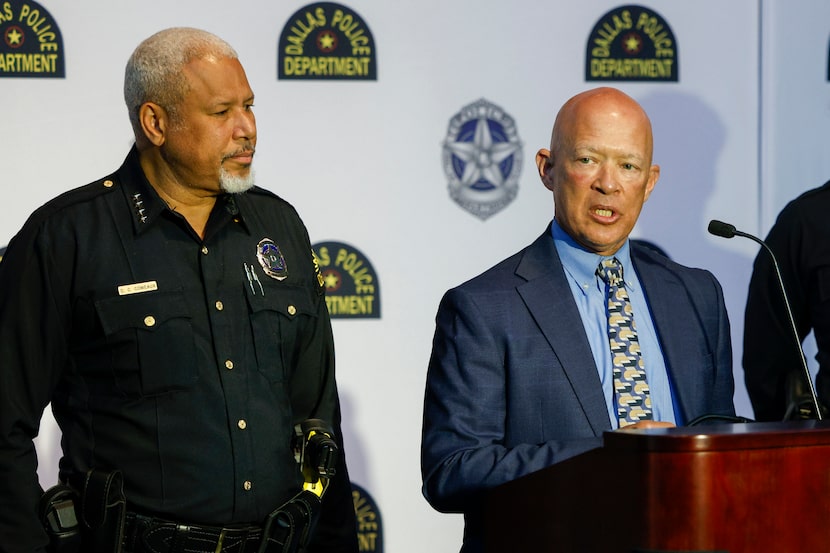

Dallas County District Attorney John Creuzot speaks alongside Dallas police Chief Daniel Comeaux during a news conference at Jack Evans Police Headquarters, Thursday, June 5, 2025, in Dallas.

Elías Valverde II / Staff Photographer

“We need to bring to bear all of the resources in the community to deal with this population that is costing taxpayers enormous amounts of money and taking up a lot of police officers’ time,” Creuzot said.

Stopping the cycle

Participation in such deflection programs are voluntary, but the goal is to provide clients with services to help stop the cycle of arrest and release, said Carol Lucky, CEO of North Texas Behavioral Health Authority.

Of the 3,539 criminal trespass arrests in Dallas County since 2024, almost half were people arrested two to nine times each on the same charge, according to data provided by the district attorney’s office. In that period 162 people were arrested 10 to 19 times on the same trespass charge.

“If you can assist people in seeking treatment, you identify what their needs are that lead them to the behavior that gets them in trouble and intervene,” Lucky said.

For the pilot, the Austin Street transition center pilot is open to criminal trespass suspects brought in by DART police but has the potential to expand to more law enforcement agencies and other nonviolent offenses, said Austin Street executive director Daniel Roby. In its first month, the transition center served 11 clients, according to Palmer.

Valerie Palmer, director of housing coordination for Austin Street Center, pictured in the men’s dorm at the Austin Street Center, Thursday, Nov. 6, 2025, in Dallas.

Elías Valverde II / Staff Photographer

Because the transition center is not a court program, participants are not required to complete treatment in order to avoid a criminal charge, Creuzot said. If police encounter an individual on suspicion of criminal trespass and the person agrees to go to Austin Street instead of jail, no charge will be generated in the first place.

Instead they will first get basic needs of food, water and shelter met. Then the process begins to see what their mental health needs are, including access to a psychiatrist or medication, Lucky said.

NTBHA is contributing about $750,000 annually to run the transition center, according to Lucky.

“That’s what this program is for,” said Palmer, “to bring families together or to help the individual gain some independence outside of living in places not meant for habitation.”

Strain on jail

In recent months, the Dallas County Jail population has averaged around 7,000 people, putting it dangerously close to capacity, according to data published by the criminal justice department.

Historically, most people incarcerated there have a history of mental health issues. In 2024, 57% of people booked in had received state mental health services within the prior three years.

County Administrator Darryl Martin has said the county must look towards ways to divert people with mental illness from ending up in jail in the first place.

Earlier this year, he created a task force of county officials, mental health professionals, judges and others to explore a model launched in Miami-Dade County, Fla., 20 years ago. It focuses on pre- and post arrest diversion programs to provide people with mental illnesses and substance abuse treatment instead of jail.

“You’ve got to find the low hanging fruit, the people who can get out of jail who don’t belong there,” Martin said.

A key aspect of the model are crisis stabilization centers, where police can take people in need of mental health treatment, detox and other services.

Before the Austin Street transition center, the Dallas County district attorney’s office partnered with behavioral health care agency Homeward Bound to provide such an alternative for law enforcement.

Since 2022, with about $750,000 in annual funding from North Texas Behavioral Health Authority, Homeward Bound’s southern Dallas treatment facility opens 16 beds for law enforcement to bring people suspected of criminal trespass instead of jail.

The program, called Dallas Deflects, treated 918 people last fiscal year, according to Homeward Bound executive director Doug Denton. About 43% were brought in by law enforcement, primarily DART police and the Dallas Police Department.

Dallas County District Attorney John Creuzot, left, and Homeward Bound executive director Doug Denton in 2020 near the entrance to what would become the deflection center at Homeward Bound.

Ben Torres / Special Contributor

The rest entered through Homeward Bound’s rapid response team. This team responds to complaints from convenience station managers who call the behavioral health center, instead of 911, about a person loitering or creating a disturbance.

Denton said even though more than half of the deflection center clients enter without making contact with police, it’s still helping to alleviate the jail population. In many cases, his team’s interventions prevent incidents from escalating into violence, he said. After their deflection assessment, some clients transition into Homeward Bound’s substance abuse treatment, detox program or long-term mental health program.

“If we can help the police by going out there and engaging these folks that are unstable in the community, then we’re fulfilling our mission,” Denton said.

But Creuzot, the district attorney, said he wants deflection centers to be utilized more consistently by police, serving as a direct diversion from the jail, and hopes the Austin Street center can provide another option.

Garland Police Chief Jeff Bryan said the biggest challenge with Dallas Deflects is the distance, which can be a two-hour round trip for Garland officers.

Officers often have to drive past the jail to make it to Dallas Deflects, underscoring the need for more deflection centers to make an impact.

“As police officers, our job is to enforce the law and traditionally that’s meant jail was the default option,” Bryan said in an email to The Dallas Morning News. “For some offenders, that’s still the right outcome. But many others just need help building a bridge to a better path. That’s why you’re seeing more agencies, including Garland PD, focus on alternatives beyond enforcement.”

Looking ahead

While Sommerman, the county commissioner, said the goal is to create four deflection centers across the county, including an expansion at Austin Street, the challenge ahead is identifying funds to launch the programs and securing agreements with providers to run them. He said some money could come from settlement funds the county received from opioid litigation – but the county will have to look for other governmental sources and philanthropy to keep them running.

Neither Lucky nor Austin Street Executive Director Daniel Roby could say how many beds might be realistic for an expansion. But Sommerman said he’d like to see 100 beds at Austin Street serving as a deflection center.

DART is one of the top agencies bringing people to the jail on criminal trespass charges, but Chief Charles Cato notes it is also the main referral for Dallas Deflects, and now the Austin Street center. With promise already shown in the model, he said he’d like to see it expand across the county.

“Jail is not the ideal environment for mental health treatment or unhoused people,” Cato said. “So the more options we have the more proactive we’re able to be in removing these people from the system in a way that doesn’t criminalize them, but instead provides resources for long-term solutions.”