Credit: Google Streetview

Credit: Google Streetview

When a man bought an Addison townhome at a foreclosure auction in October, he found the deceased body of its elderly prior owner. The case highlights risks every foreclosure buyer should be aware of — and offers lessons for homeowners and neighbors alike.

Buying at foreclosure auctions comes with some “as is” risks. In Texas, these sales are held on the first Tuesday of every month, typically on the courthouse steps, where properties are auctioned to the highest cash bidder. Buyers cannot usually enter or inspect the home beforehand, and the sale is considered final — meaning the property is transferred as is, with all physical conditions becoming the new owner’s responsibility.

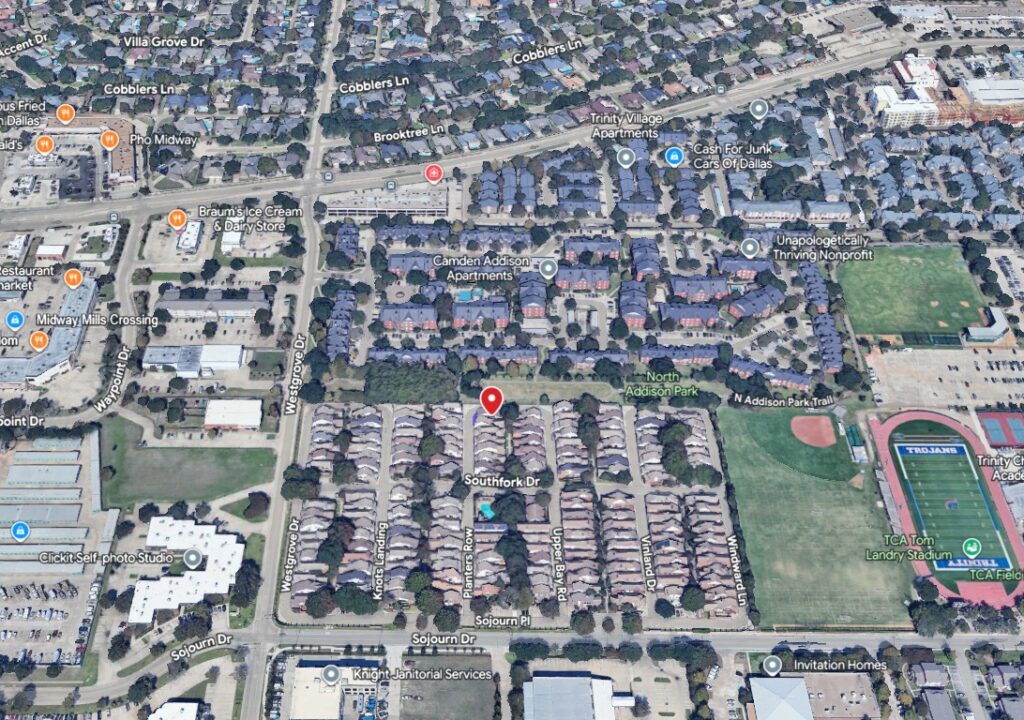

The foreclosed property in this case is a brick and stucco garden home at 17118 Planters Row — a two-bedroom, two-bath with 1,426 square feet. Built in 1983, it last sold in 2004. In MLS, it was described as an open, airy home located next to a greenbelt and small park, with a loft study, private patio, and two-car garage in the Homes at Addison Place, located near Trinity Christian Academy at Westgrove and Trinity Mills Rd.

Credit: Google Maps

Credit: Google Maps

The home went to auction on Tuesday, Oct. 7, selling to an unnamed buyer for an undisclosed amount. Later, the new owner visited the property and noticed a strong, foul odor, prompting him to call police.

When Addison Police arrived, they entered the home and discovered the body of 69-year-old Pauline Williams in the living room. Authorities said she appeared to have been deceased “for some time.” The Dallas County Medical Examiner has not yet determined the manner of death.

Neighbors told local media the home’s mailbox was full and the side yard overgrown — signs that might have suggested something was amiss — yet no one apparently knocked, checked, or called. In hindsight, one neighbor told WFAA they regretted not checking on Williams. Dallas County Appraisal District records show she had lived in the home since 2005.

MLS records show that Williams purchased the home in 2004 using a $118,400 conventional loan at a fixed 6.5% interest rate. By 2025, the foreclosure posting listed a $145,659 lien against the home — a number reflecting accumulated unpaid interest, fees, and costs.

Between an independent appraiser and the Dallas County Appraisal District, the property was valued between $318,000 and $377,000. With such a value, Williams had substantial equity. Had the home been listed for sale instead of going into foreclosure, she likely would have netted approximately $200,000 after paying off the lien.

So how does a homeowner with significant potential equity still lose a property to foreclosure?

Mortgage lender Lisa Peters of First Horizon Bank says the answer often comes down to a lack of information and communication.

Lisa Peters

Lisa Peters

“Anyone who bought in 2004 would have plenty of equity in the home,” Peters said. “But if she did not know what her options were and no one counseled her about help available, then this kind of foreclosure can happen. Also, when the lender has no communication with the borrower, and they’re left with no options, then they do what they have to do.”

But Peters explained that most banks don’t relish foreclosing a single, elderly woman’s home.

“Lenders don’t want foreclosures,” Peters said. “They’ll bend over backwards not to foreclose on a home. That wasn’t always the case. Back in the 2000s, banks had large foreclosure departments… but nowadays, many banks aren’t set up for that.”

“But the problem is that you can’t ignore it,” Peters added. “A homeowner can call the loan servicer to ask for help. Every loan packet we do, we include information about resources to help homeowners if they get into financial trouble.”

She noted that property tax issues can also be manageable for older homeowners.

“For property taxes, for example, there’s places you can go for help with filing homestead or over 65 exemptions. And actually if you’re over 65, you can defer them — basically not pay — and the taxes will come due when it’s time to sell,” Peters said.

For investors who eye foreclosure auctions as a discounted entry into homeownership, this case underscores just how opaque these purchases can be. “As is” may involve far more than cosmetic updates or deferred maintenance.

Title searches, lien checks, and public records might catch financial and legal red flags — but they don’t reveal whether the prior occupant is still living there. A foreclosure listing site generally warns, “The properties may be occupied; do not disturb the occupants.” Unless someone physically checks the property before sale, the risk remains hidden until after purchase.

“Lenders may have a management company that goes in and makes a home ready for sale, but in this case with a courthouse steps foreclosure sale, there’s typically no inspection,” Peters said.

Even though the foreclosure notice urges bidders to investigate the property’s “nature and physical condition,” such investigation is often impossible without access.

Credit: Google Streetview

Credit: Google Streetview

Beyond investor risk, the situation raises broader questions about neighborhood awareness. What happens when a home falls silent for months? When mail piles up, and grass grows tall, but no one checks in? It raises questions about community vigilance and the safeguards (or lack thereof) in foreclosure pipelines, but it’s also a reminder that a simple knock on the door — or even a police welfare check — can stem an unseen tragedy.

For buyers and investors, the takeaway is simple: foreclosure sales may offer discounted prices, but they also carry hidden risks that extend beyond deferred maintenance or cosmetic issues. Properties are sold as-is, with no guarantees about condition or occupancy, and what appears to be a bargain can quickly turn into an unforeseen problem. In cases like this one, the human element — absentee homeowners, overlooked signs of trouble, and gaps in neighborhood awareness — underscores that real estate transactions are about more than numbers on a page.