Teenagers suspected of gunning down a security guard at a CVS in downtown Dallas. A man who used a dating app to talk his way into a Lake Highlands apartment before robbing his match. A woman accused of stealing from a north Oak Cliff convenience store and flashing a gun before driving off.

Images of those suspects were among dozens Dallas police ran through an artificial-intelligence facial recognition platform during the department’s first months under contract to use the technology, according to newly obtained internal police records and related court filings reviewed by The Dallas Morning News.

Dallas police are weighing whether to use facial recognition in a broader range of criminal investigations. The Dallas Morning News reviewed hundreds of internal records, police reports and arrest-warrant affidavits to understand how the department has used the powerful technology so far.

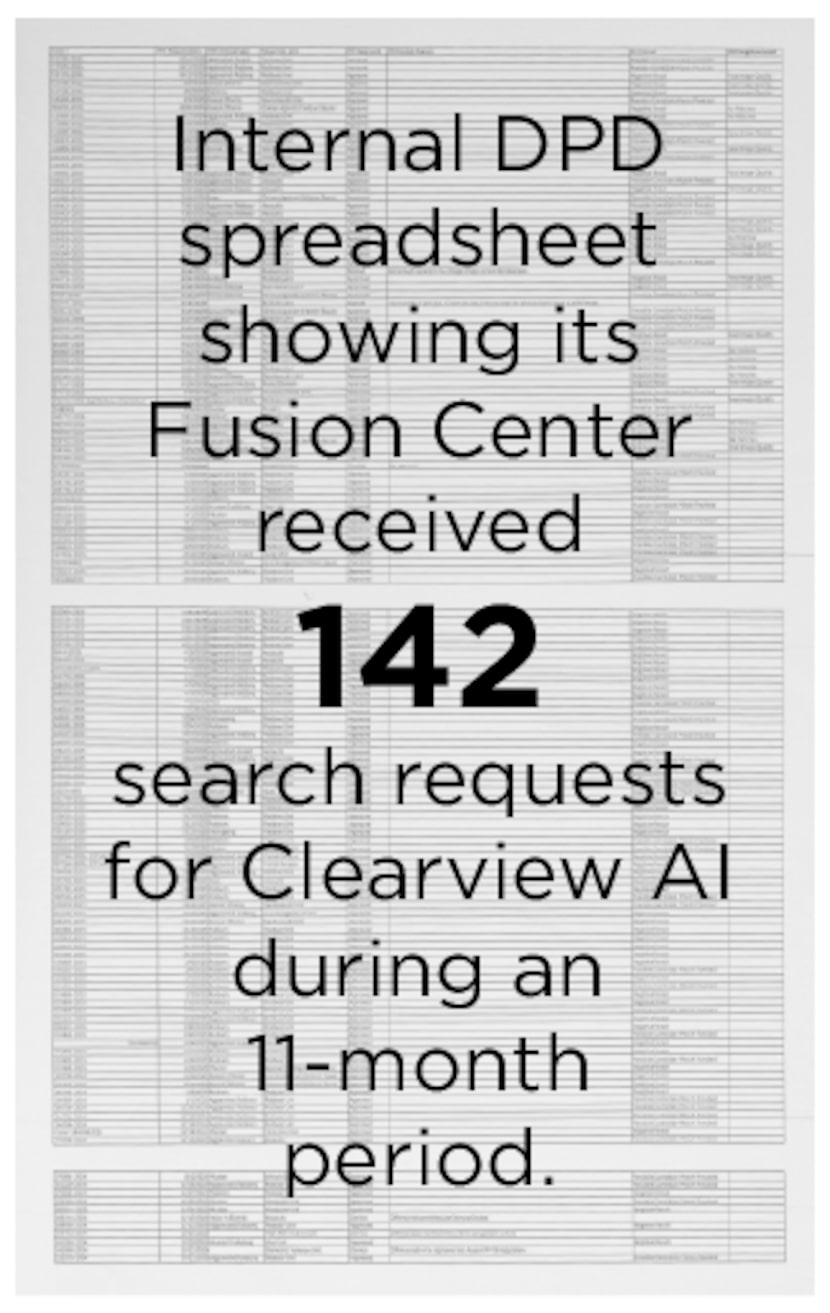

An internal police spreadsheet obtained by The News shows the department logged more than 140 facial recognition search requests in cases ranging from sex crimes and human trafficking to robbery and homicide. The spreadsheet lists searches entered between October 2024 — when the tool was rolled out — and September.

The News’ review offers a partial glimpse of how the department is using Clearview AI, a powerful and controversial facial recognition platform that has drawn privacy concerns in the United States and regulatory crackdowns abroad. The department is also weighing whether to expand the tool’s permitted use beyond mostly violent felonies and sexual offenses to include certain misdemeanor cases.

Breaking News

Since the tool’s rollout last October, the public record on the department’s investigative outcomes resulting from Clearview searches is thin. The department has said little publicly about what ultimately comes of cases in which Clearview is used — a gap two privacy-law attorneys tracking the spread and use of facial recognition technology told The News warrants closer scrutiny.

In May 2024, then-police Chief Eddie García touted the technology as a “game changer” for the department’s investigators.

The department, the chief told the City Council’s public safety committee, was taking a measured approach to implementing the technology, waiting to study it and draft “robust” rules first rather than becoming an early adopter. The committee signed off on the plan after a brief discussion, unanimously approving it and clearing the way for the department to roll out the tool.

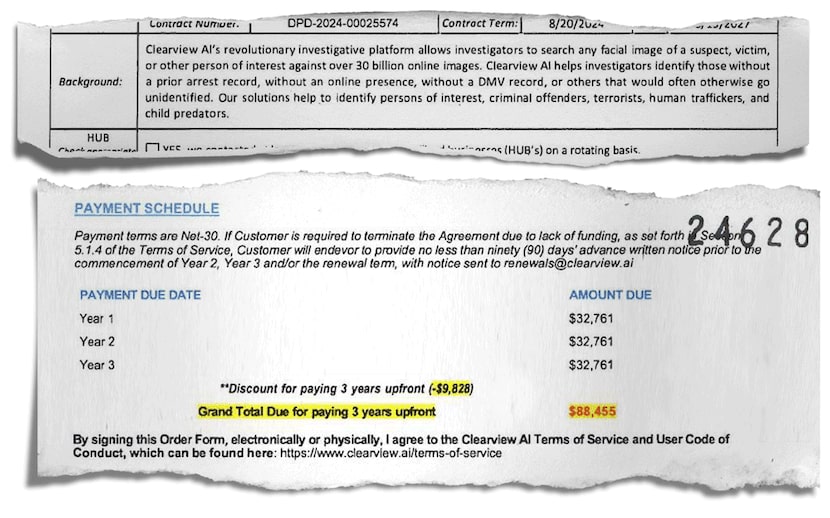

Dallas paid $88,455 for the platform entirely with a grant through the Department of Homeland Security, according to records obtained by The News.

Now, more than a year later, a department spokesperson said the tool has aided investigators. They declined to make officials available for an interview to discuss how exactly the tool is being used, what outcomes they have seen, and their considerations for adding certain misdemeanor crimes.

“The facial recognition software is one of the many tools our detectives have,” Corbin Rubinson, the police spokesperson, wrote in a recent statement, “and it has proven useful in criminal investigations. We continually look for new technology and techniques to be more efficient and effective in keeping Dallas safe.”

Attorney Nathan Freed Wessler, deputy director of the Speech, Privacy and Technology Project for the national ACLU office, said the role facial recognition plays tends to be “extraordinarily overstated by the technology vendors and often by police departments.”

Aside from the effectiveness, Wessler and others tracking the technology’s use are concerned that police might lean too heavily on a possible match.

“There are lots of ways that someone could come to be arrested,” he said in an interview. If an agency is using facial recognition, he added, it should at the very least be “only one of a number of investigative steps that police take.”

Hoan Ton-That, a Clearview AI founder, demonstrated the company’s facial recognition software using a photo of himself in New York on Tuesday, Feb. 22, 2022. (Seth Wenig/The Associated Press)

Seth Wenig / AP

Technology raises alarms

Across the country, civil liberties groups and defense attorneys have raised alarms about the technology, pointing to a number of documented wrongful arrests in which police leaned on a bad facial recognition match. They warn that the systems, particularly earlier generations, are less accurate on people of color, women and young people, and that once a misidentification is folded into an investigation, it can be difficult to unwind.

Clearview scrapes tens of billions of photos from social media and other public websites to create a face-print database for law-enforcement searches. Now used by agencies across the country, the New York-based company has argued its methods are among the world’s most accurate for positively identifying faces, including those of people of color.

Still unsettled, critics like Wessler say, is a larger fight over privacy and the company’s mass collection of billions of photos from the web.

Since 2020, when reporting by The New York Times first brought the company’s work to wide attention, Clearview has faced a patchwork of lawsuits and state- and local-level challenges and restrictions on how its technology is used.

Those actions have imposed limits and costs at times, but have stopped short of banning Clearview or leading to broad, meaningful limits on the tool’s use or those like it, said Andrew Guthrie Ferguson, a law professor at George Washington University Law School. As a result, it is sometimes up to local agencies to self-regulate.

Last year, prior to the Clearview rollout in Dallas, department leadership outlined new internal rules for facial recognition technology. The rules, they said, were meant in part to ease civil liberties concerns.

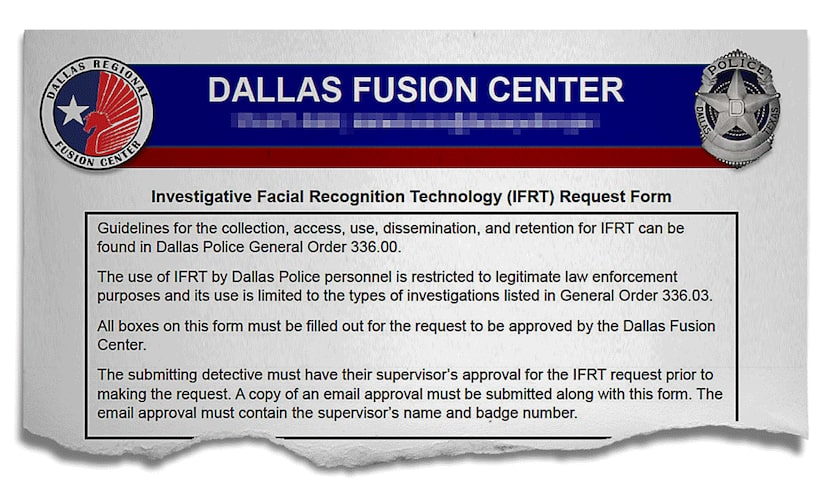

For example, a possible face match on its own would not amount to probable cause for an arrest. The tool was limited to certain felony and sexual offense cases — a scope the department is now weighing whether to expand — and could not be used to scan livestreams or images of First Amendment activity, such as protests. Detectives also had to get a supervisor’s approval and could run searches only after a crime had occurred.

“The City is making us follow VERY tight rules for facial recognition,” an analyst in the department’s Fusion Center — the city’s crime-intelligence hub where Clearview is used — wrote in a March email to a robbery detective, reminding them to complete a required form before a search could be run.

At the Dallas Police Department’s Fusion Center, the city’s crime-intelligence hub, investigators must fill out this request form before running a facial recognition search with Clearview AI, including, among other case details, the name of the supervisor who approved it.

Dallas Police Department

Since the rollout, the primary way for the public to see how the department is using the tool has been six-month updates issued to council members through memos.

In those memos, the department has limited its disclosures to a tally of facial recognition searches and the number of investigative “leads” those searches generated.

As a result, it’s unclear how the tool has shaped criminal investigations.

In a July article on TechHalo — an online platform where public safety agencies share how they use emerging technology — Maj. Brian Lamberson, who oversees the Fusion Center, said Clearview had “dramatically” sped up investigations of violent offenses.

“The leads generated by our analysts and detectives,” he’s quoted in the article, “have led to multiple arrests for violent offenses — five that are confirmed, with likely more.”

Using the internal spreadsheet as a road map, The News filed open-record requests for the underlying police reports and internal Clearview search requests.

Dallas Police Department

Records show the tool helped steer investigations in a range of felony cases, including fatal shootings, in the department’s first 11 months with it. Most of the offenses in those cases were reported in that same period.

In that period, just under 40% of the department’s Clearview searches resulted in a “possible candidate match,” according to The News’ review of the internal spreadsheet. In those cases, the software typically returns images it has flagged as potential matches, along with links to the public websites where those photos appeared.

In the same period, police most often used Clearview in robbery investigations; robberies and aggravated robberies accounted for more than half of all searches.

The tool does not always help. Clearview searches for the fatal downtown CVS shooting and the alleged theft at the north Oak Cliff convenience store returned “negative” results, the spreadsheet shows. Suspects in both those cases were arrested through other means.

Seven requests to the Fusion Center to run a Clearview search were rejected, according to the spreadsheet, either because they lacked supervisory approval, the offense was not eligible or the platform would not accept the photos due to poor image quality.

The review identified one case that has already led to a conviction.

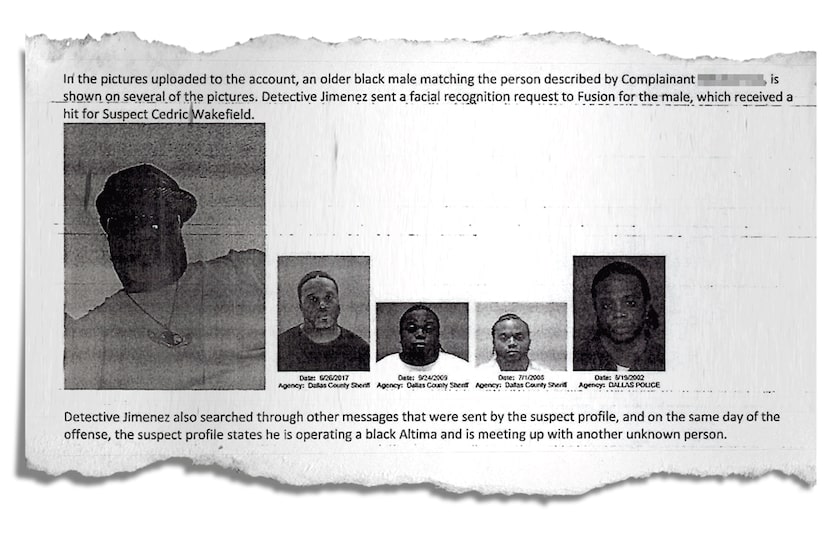

In February, investigators tied Cedric Wakefield to the Lake Highlands apartment robbery after he used a dating app under a different name and photo to arrange a meeting at the victim’s home. According to an arrest-warrant affidavit, he arrived with a handgun, held the victim at gunpoint and stole an iPhone, a Nintendo Wii, a computer monitor and a wallet.

A detective subpoenaed the app and obtained previously uploaded photos linked to Wakefield’s account. With those images in hand, the detective asked the Fusion Center to run a Clearview search, which produced a possible match for Wakefield. Police arrested him during a traffic stop in far northeast Dallas five weeks after the robbery.

It’s unclear exactly how much facial recognition factored into the case’s outcome. The detective also relied on other tools and methods, including an interview with the victim, the city’s network of automatic license plate readers and information obtained from the subpoena for the dating app.

In September, Wakefield, now 50, took a plea bargain and pleaded guilty to aggravated robbery, a first-degree felony, court records show. He was sentenced to five years in prison.

A Dallas police detective’s arrest-warrant affidavit describes requesting the Dallas Police Department’s Fusion Center to run a facial recognition search on a February armed robbery case, which returns a “hit” for Cedric Wakefield. Months later, Wakefield pleaded guilty to aggravated robbery and was sentenced to five years in prison.

Dallas Police Department

Rule changes — and wider use — may be coming

Last month, a department higher-up said changes were coming to the police’s rules governing the use of facial recognition technology.

During a meeting of the City Council’s public safety committee, Assistant Chief Mark Villarreal said the department wants to broaden the kinds of cases in which the technology can be used.

Instead of limiting it to violent felonies and sexual offenses, he explained, detectives would be able to deploy the tool in “Class B misdemeanors and above,” particularly in property crimes.

Under Texas law, a Class B misdemeanor is punishable by up to 180 days in county jail, a $2,000 fine or both. It can include offenses such as a first-time DWI, theft of property worth at least $100 but less than $750 and criminal mischief causing damage in the same dollar range.

Villarreal’s remarks were in response to a question from Mayor Pro Tem Jesse Moreno, who is vice chair of the committee. The District 2 representative asked whether the technology could be used to pursue “porch pirates,” a colloquial term for thieves who steal packages delivered outside people’s homes.

Villarreal said he expects the tool will make the department more effective at combating that kind of property crime. The change would come early in the second year of the department’s Clearview contract.

City of Dallas contract paperwork describes Clearview AI’s facial recognition tool and outlines a payment schedule totaling $88,455, paid for through a federal Department of Homeland Security grant.

Dallas Police Department

Ferguson, the George Washington University Law School professor, said that shift underscores how a policy written and controlled by police without oversight from the City Council or courts can quietly expand before the public has a real chance to understand or debate it.

“What started out as a very limited grant of power,” Ferguson said in an interview, “can easily expand and change based on essentially the whims of the police without sufficient debate or discussion by the citizens who are subject to this technology.”

To Wessler, the ACLU attorney, such an expansion almost certainly means police will use the tool more often — and with that, he said, the chances for misuse or abuse will grow.

“Most of the wrongful arrest cases that we know about,” he explained, “are [for] pretty low-level offenses. It reinforces how the dynamic gets worse when you start using this very flawed but very powerful technology for petty stuff.”