Change in Fort Worth’s Northside is inevitable, residents say, but it could go one of two ways.

In one future, Northside is preserved as a Hispanic cultural hub with small, family-owned restaurants and community festivals at Marine Park. Its bright, colorful homes still overlook driveways full of cars — often two for each of the three generations that occupy them.

Gazing into the other future, those homes are flipped with freshly painted monochromatic exteriors, filled with modern amenities and surrounded by newly planted turf, the neighborhood’s longtime residents bought out or defeated by rising housing costs and taxes.

The historic neighborhood’s dilemma is shared by communities across Fort Worth as the growing population grapples with rapidly rising housing costs. The city reached 1 million residents this year, and more are moving in, with estimates showing Fort Worth will add another 400,000 people by 2050.

This is part of the Report’s special 1 Million & Counting growth series, which will be published on Mondays into October. The reporting will lead to a growth summit Oct. 23 at the downtown Tarrant County College Trinity River Campus.

The growth has spurred citywide developments that are dense with apartments, multifamily construction and new subdivisions cropping up in the city’s urban core and on its outskirts.

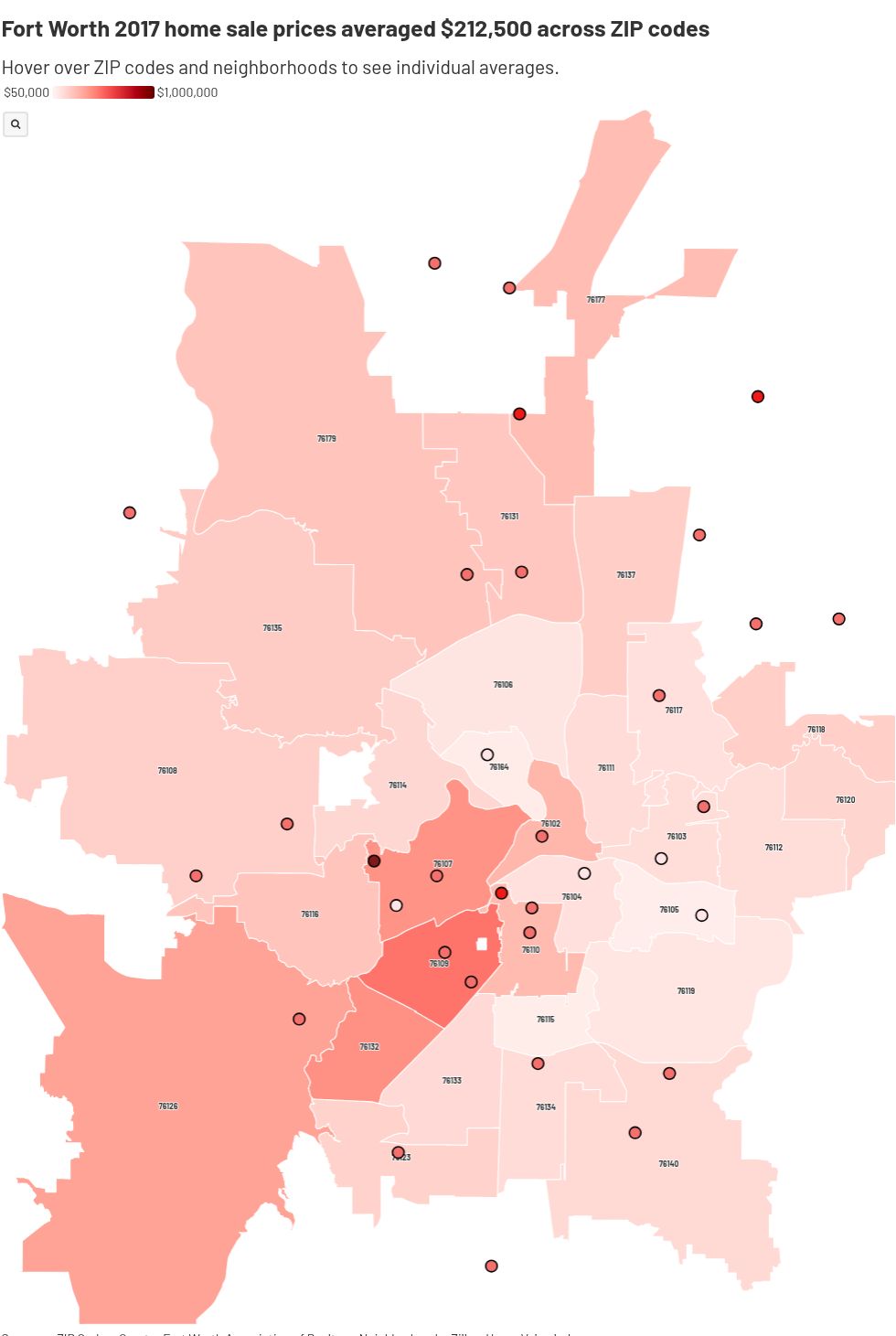

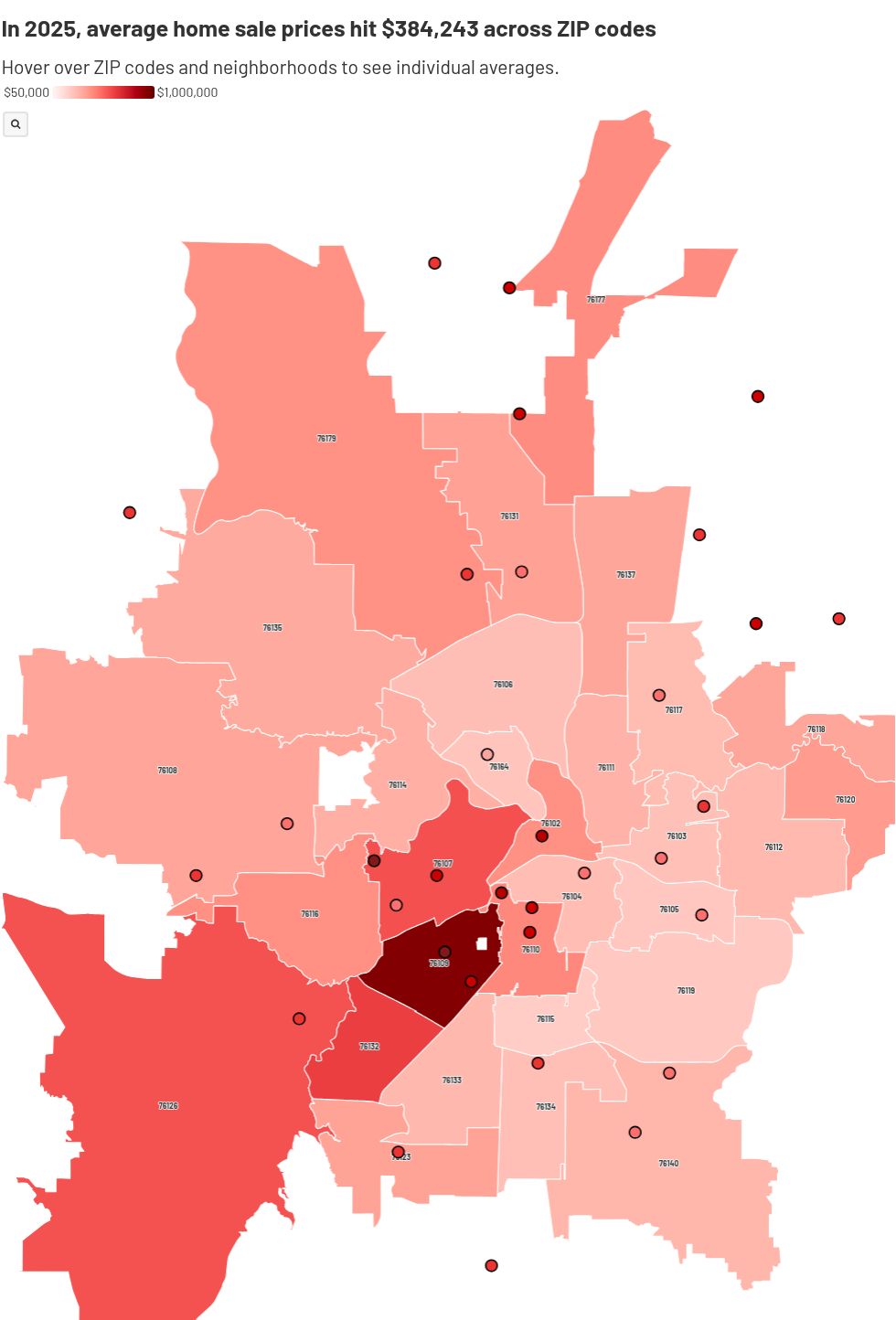

But as Fort Worth attracts new visitors and investors, demand outpaces housing supply, Realtors say. And in the face of rising construction costs and inflation, average home sale prices have risen about 190% since 2010, according to estimates from the U.S. Housing and Urban Development Department.

Residents of Northside, sandwiched between the booming Stockyards and promising Panther Island, face rising property taxes and pressure from investors to sell their homes. Many have fixed incomes and fear they will eventually be forced to move, said Rosalinda Escobar Martinez, who was a member of parent-teacher associations in the area over the 2010s.

“When we first moved into the neighborhood, houses were less than $50,000, and now some are like $300,000,” said Martinez, who moved into the neighborhood more than 20 years ago.

Between 2017 and 2025, Fort Worth’s population grew by 16% — faster than Texas’ average of about 12.5%, census estimates report. In that same amount of time, the city’s average single-family home value rose from $188,536 to $305,476, according to the Tarrant Appraisal District.

Average rental costs have also increased, doubling from $700 in 2010 to $1,455 in the Fort Worth-Arlington area, according to Housing and Urban Development reports.

The more people move into the city, the higher demand for houses and property values rise, said Becky Gligo, executive director of Fort Worth Community Land Trust, which works to help would-be buyers afford houses.

“Some people have access and income to sustain the change. But the ones that don’t, it’s very hard to see,” said Arturo Martinez, Rosalinda’s husband, whose family has lived in Northside for six decades.

Arturo and Rosalinda Escobar Martinez pose for a photo in front of their house in Fort Worth’s Northside on Oct. 9, 2025. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

Arturo and Rosalinda Escobar Martinez pose for a photo in front of their house in Fort Worth’s Northside on Oct. 9, 2025. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

How have home values changed since 2020?

Average value of Fort Worth single-family homes:

In 2020: $209,084

In 2025: $305,476

This has led to an about $1,100 increase in the average homeowner’s property tax bills, which now average about $6,600 annually, according to calculations by the Report that factored in taxing entities’ changing rates.

The city’s high housing costs and the nation’s higher interest rates are preventing prospective homebuyers from purchasing and discouraging current homeowners from selling, said Donna VanNess, president of Housing Channel, a nonprofit advocating for sustainable homeownership.

Housing costs spiked locally after the COVID-19 pandemic, VanNess noted. Around that time, corporations and equity firms began buying massive swaths of neighborhoods to rent out homes or rebuild. By 2024, the city found that corporations owned 26% of Fort Worth homes.

Rising prices inside the 820 Loop

Two decades ago, Fort Worth had a relatively affordable housing market, recalled Fernando Costa, a former longtime assistant city manager. That made Fort Worth competitive as an attractive place for workers to live and businesses to grow.

But the city has struggled to keep prices low, Costa said.

In 2023, City Council adopted a housing affordability strategy, laying out initiatives to encourage and assist prospective homebuyers with expanded assistance programs and more affordable housing development.

The report found that a median-income family in Fort Worth, making about $75,000, could not afford a median-priced home and identified neighborhoods at risk of displacement.

The strategy emphasized affordability concerns in Fort Worth’s historic neighborhoods, including Northside.

Potential gentrification of the neighborhood has been the subject of national studies due to the anticipation of future Stockyards-area and Panther Island development, Costa said.

While these projects include new entertainment, hotel and business spaces, some residents fear they also could drive out businesses and families who have occupied the neighborhood for generations.

What is gentrification?

Gentrification is the process in which previously disinvested, low-value areas attract real estate investment and a demographic shift, with higher-income residents moving in and increasing property values. This often results in an increase in property values and the displacement of earlier, usually poorer residents, according to the Urban Land Institute.

A pile of rubble sits near a new development in Fort Worth’s Northside on Oct. 1, 2025. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

A pile of rubble sits near a new development in Fort Worth’s Northside on Oct. 1, 2025. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

A 2024 study conducted by the Urban Land Institute recommended various actions to help prevent gentrification. Among them was creating a state-recognized Northside cultural district, like the one covering Near Southside’s Magnolia and South Main villages. Development of “missing middle” housing in the form of duplexes, triplexes, townhouses and small apartment buildings is also recommended.

The study suggested a community action committee that advocates for neighborhood improvements, like the newly formed Historic Northside District, which is affiliated with Main Street America.

The district advocates for preservation of the neighborhood’s arts and Hispanic culture. It’s headed by the Hispanic Chamber of Commerce but is seeking independence.

The Martinez family is deeply connected to their community. Over the 2010s, Arturo sat on Fort Worth’s Human Relations Commission and the Art Commission for a combined eight years. He’s watched city officials continue to make decisions about the Stockyards’ future.

“But how inclusive is it to neighborhoods?” Martinez said. “What are their benefits to the restaurants and barber shops and local things that bring the culture that they seek and look for?”

Other historic neighborhoods such as Historic Southside and Lake Como — both predominantly Black communities — face similar gentrification concerns as residents there are in conversation about preservation investments.

Fort Worth City Council member Carlos Flores, a lifelong resident of the Northside area he now represents, acknowledges that the neighborhood faces some potential gentrification. But that’s not the primary cause of rising housing prices, he said.

Northside sits along the West Fork of the Trinity River, between Interstate 35 and Texas 199. The area is naturally attractive to developers for its relatively low-cost properties and connection to downtown, Flores said.

Because of this, investors often buy old houses, flip them and resell for a higher price.

“The real estate and construction markets are responding to a need,” Flores said. “People want newer homes, and they’re going to be looking for them, and they want them in centralized areas.”

Carlos Flores speaks during the Trinity River Vision Authority board meeting in Fort Worth July 31, 2025. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

Carlos Flores speaks during the Trinity River Vision Authority board meeting in Fort Worth July 31, 2025. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

On the other side of downtown, neighborhoods in Near Southside saw a similar transformation. The homes now run for significantly more than the city’s average home sale price, with an average price of around $430,000, according to the Greater Fort Worth Association of Realtors.

In Fairmount, a nationally registered historic neighborhood, oak-lined streets outline Craftsman bungalows and four-square homes with white picket fences and Victorian awnings.

The area, formed in the early 1900s, saw its growth driven by the streetcar transit connecting it to downtown. It evolved as a predominantly white middle-class neighborhood with a few large houses strewn about, and is historically wealthier than Northside, which grew as the nearby Stockyards demanded workers for its meatpacking industry.

About 2,500 people live in Fairmount, a National Historic District in Near Southside. (Drew Shaw | Fort Worth Report)

About 2,500 people live in Fairmount, a National Historic District in Near Southside. (Drew Shaw | Fort Worth Report)

While multiple factors contribute to Fairmount’s higher price tag, a central one was the city’s intentional efforts over the 1980s and 2000s to encourage business development in Near Southside and to provide tax incentives to restore historic homes, Costa said.

“That effort was a resounding success,” Costa said. “However one chooses to view it, it had the effect of raising housing prices dramatically in Fairmount. Whereas 30 years ago, housing was highly affordable, today it’s not.”

Housing prices fueled by growth, expansion

Fort Worth’s housing market is nearly healthy from a Realtor’s perspective, said Paul Epperley, president of the local Realtors association. But demand still outpaces supply, even as houses are built.

Fort Worth added about 36,000 new single-family houses since 2020, according to the appraisal district. Most of these have expanded the city’s borders well beyond the 820 Loop.

In the far north, once sprawling ranchland is now parceled into new subdivisions, such as those around Bonds Ranch and Alliance.

Houses sit next to undeveloped land June 20, 2025, off West Bonds Ranch Road in Fort Worth. (Mary Abby Goss | Fort Worth Report)

Houses sit next to undeveloped land June 20, 2025, off West Bonds Ranch Road in Fort Worth. (Mary Abby Goss | Fort Worth Report)

Since Russell Fuller bought his home near Keller’s border 20 years ago, his house’s worth has doubled. Fuller is president of North Fort Worth Alliance, a group of 47 communities and neighborhood associations.

The new houses up north are mostly home to dual-income families, many of whom moved in from out of state, Fuller said. They’re often attracted to the area’s new houses and schools, which academically outperform those in Fort Worth ISD.

Fuller said longtime residents aren’t moving, which drives up prices, too. Homeowners like him, who bought houses decades ago and might be ready to downsize, aren’t finding options that meet their needs and price range in or around Fort Worth.

If they did move, they’d face considerably higher interest rates, likely 3 or 4 percentage points higher than what they’ve secured, notes Epperley, of the local Realtors group.

“There’s no place for us to move to,” Fuller said. “Therefore, there’s nobody to vacate the lower-priced houses for new people.”

Solutions require ‘more tools in our toolbox’

No one solution will make homes more affordable, said Gligo of the Community Land Trust.

City officials could offer some tax relief that would allow homeowners to leave the property to their heirs, she said. Home incentives, such as the one seen in Fairmount, could allow longtime residents to tackle expensive needed repairs that sometimes make selling to a developer the better option.

“The more folks we have coming to the table, and the more tools in our toolbox, the better,” she said.

Curbing housing’s rising cost was a priority for state lawmakers heading into the 2025 legislative session. New Texas laws limit how major cities can regulate housing developments, as well as make it easier to build smaller houses on smaller lots and convert old buildings along retail corridors into apartments and mixed-use developments.

In November’s election, Texas voters will weigh several propositions that increase the homestead exemption and create new tax breaks for homeowners.

Housing affordability concerns also show up at meetings in City Hall, where council members are floating the idea of including a $5 million housing proposition in an expected bond proposal next year that would go to affordable housing projects.

Fort Worth is the largest city in Texas that has not included a housing proposition in a bond. In 2024, Dallas voters approved that city’s first bond propositions specifically dedicated to housing efforts, including $26.4 million to fund affordable housing construction and neighborhood revitalization.

Another strategy, favored by Fuller, is to freeze property taxes for homeowners in specific areas at risk of gentrification. For instance, if a Northside resident bought their house for $150,000 a decade ago, they could continue paying taxes on that price as long as they live there, no matter the appraised value.

Flores noted the city has taken many steps to help homeowners, including the continuous reduction of tax rates.

He pointed to Fort Worth’s restrictions on short-term rentals and home Priority Repair Program as initiatives that help. The city also has a program that covers up to $25,000 in down payment and closing costs for eligible first-time homebuyers.

Meanwhile, developers are adding to Fort Worth’s affordable housing supply with townhomes, cottages, apartments and other efforts.

In the nonprofit sector, Gligo’s Community Land Trust buys property, renovates the houses if needed, then sells them to a qualified family making up to 120% of the area’s median income. The family owns the home, but the trust owns the land and gets first choice to buy back the house when the family decides to move.

Since the trust keeps ownership of the land, the homes stay attainable when the original owners sell.

VanNess said a big part of affordable housing is education. Housing Channel educates prospective homebuyers on how to budget, seek and negotiate for a house they can afford. She encourages neighborhoods to be more receptive to dense and affordable housing projects, such as duplexes and apartments.

Ramble & Rose, overlooking West Rosedale Street is one of the properties where Fort Worth Housing Solutions provides affordable housing opportunities. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

Ramble & Rose, overlooking West Rosedale Street is one of the properties where Fort Worth Housing Solutions provides affordable housing opportunities. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

Earlier this year, Northside residents opposed a plan to renovate the century-old Primera Baptist Church into apartments.

Multifamily proposals like this typically receive opposition from neighborhood residents who fear such developments will bring crime, traffic and overcrowding of schools, Costa said. Most of the time these issues don’t arise, but the prospect worries neighbors, housing officials say.

Affordable housing “is not a threat to the communities,” VanNess said. “We’re still doing home ownership. We’re just offering different products that make it affordable for working families.”

Arturo and Rosalinda Martinez have hope for Northside, even as the hotels and new chain restaurants open down their street.

As they wait in the busy traffic now outside their driveway, the couple dreams of the city connecting Northside with downtown by adding more direct bus lines. They’ve long advocated for building sidewalks through the neighborhood to make it more walkable.

“I am excited because, hey, now I have a Starbucks and a Chick-fil-A a block from my house, I could walk — if I had sidewalks,” Rosalinda Martinez said.

Flores is optimistic that the development around Northside will bring opportunities for residents and local businesses.

“I really do believe that the Northside will benefit from it,” he said. “At the same time, we’re trying to lay the groundwork right now, so that before that development really starts taking off, we offer ways that we can help alleviate some of these effects.”

Drew Shaw is a government accountability reporter for the Fort Worth Report. Contact him at drew.shaw@fortworthreport.org or @shawlings601.

At the Fort Worth Report, news decisions are made independently of our board members and financial supporters. Read more about our editorial independence policy here.

Related

Fort Worth Report is certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative for adhering to standards for ethical journalism.

Republish This Story

Republishing is free for noncommercial entities. Commercial entities are prohibited without a licensing agreement. Contact us for details.