A Catholic parish in Massachusetts stirred up controversy recently, enough to appear in The New York Times.

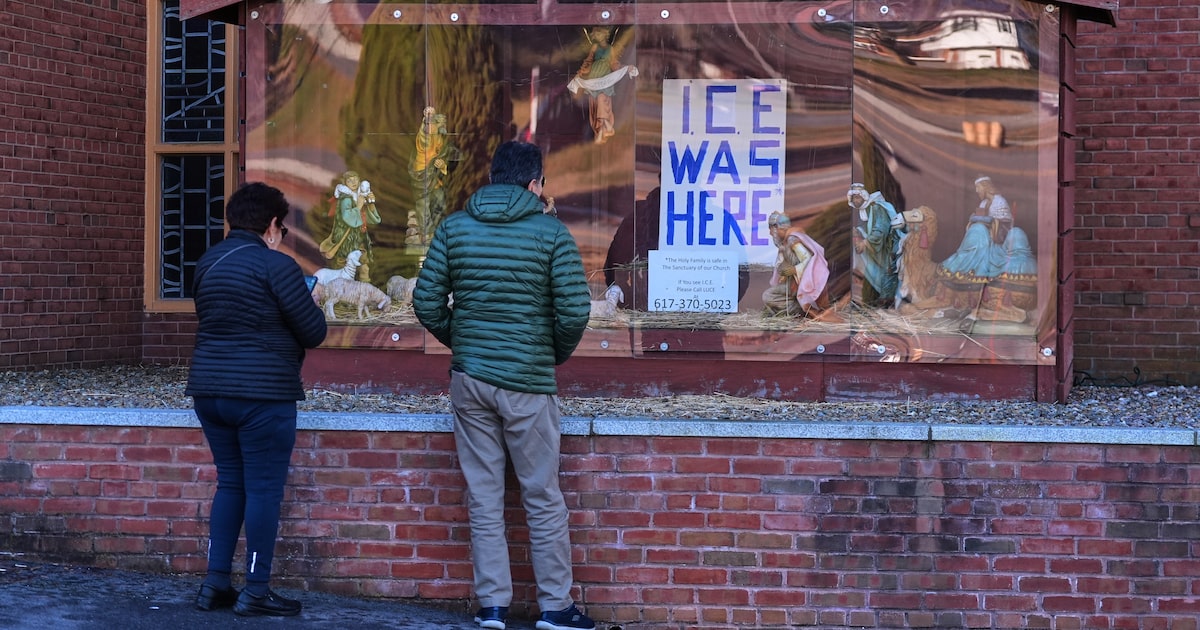

The reason was a Nativity scene displayed in front of the church. Although it had everything you’d expect (sheep, cows and shepherds) it contained no member of the Holy Family. No Mary, no Joseph, no baby Jesus. Instead, there was just a big sign: “ICE WAS HERE.” You get, I assume, what they were trying to say.

Obviously, someone complained. That complaint was then mishandled and made into a headline, if not an actual story, good fodder for another cycle of clicks, another dose of dopamine for the addicts of rage. Nothing new here, we have seen such politicized crèches for a very long time. One could argue that the original Nativity scene was itself politicized. Herod, at least, saw it that way.

This parish supposedly has a reputation for this sort of thing. One year, baby Jesus was put in a cage instead of a crib. Another year they were all knee-deep in water due to climate change. Again, I assume you understand the message. Christmas comes each time this year, and so does stuff like this.

It’s not my thing, but I get it. My guess is that the people behind it simply want us to remember that the Christmas story is also a moral story, that it should have some bearing upon the way we live our lives. This, of course, is an utterly offensive suggestion. It’s also utterly true.

Opinion

Thus, the conflict. The Archdiocese of Boston ordered the scene replaced. The parish has yet to comply. Archdiocesan officials argue that people “have the right to expect that they will encounter genuine opportunities for prayer and Catholic worship — not divisive political messaging.” To which the parish priest replied that simply because “some do not agree with our display does not make it sacrilegious.”

How should we arbitrate? What you think about it depends on your priors; and no one cares what you think anyway so long as you click on the story. Remember, the conflict is for clicks. Truth or right in this instance is irrelevant.

But setting aside for a moment my cynicism regarding the spectacle of the whole thing, even setting aside the disturbing reality underneath such politicized displays, what about the idea, put forward by church officials, that churchgoers, Catholic or otherwise, have a “right” to assume that they will not be confronted with “divisive political messages”? Is that right? Does that statement, the idea behind it, have anything to do with Christianity at all? Do you indeed have a right to go to church undisturbed by matters you deem politically divisive?

The answer is no. That is not at all correct. At least, that is, if we’re going to be serious about religion. You do not have the “right,” not in the slightest, to encounter God undisturbed. For that is the beginning of idolatry, the first word of another Gospel.

With all due respect to whoever on the archdiocesan communications team decided to say it that way, those are words born of the dark spirit of managerialism, from fear of liability, and not the Gospel of Jesus. Imagine Jesus saying such a thing. You can’t, because he wouldn’t, and nor should the Church.

Not that I’m saying we should make every crèche an instrument of protest, but that’s not what I truly fear. Rather, what I fear far more is the organizational taming of genuine Christianity, for precisely when Christianity is tamed, evil is untamed.

I mean, that’s exactly what the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. talked about. “So often the contemporary church is a weak, ineffectual voice with an uncertain sound,” he wrote from a Birmingham jail. “So often it is an archdefender of the status quo.” He said that the problem with too many Christians is that they “have been more cautious than courageous and have remained silent behind the anesthetizing security of stained-glass windows.”

But maybe he was wrong. Maybe King should have respected more the right of others to pray undisturbed. If only he had the blessing of ecclesiastical officials to tell him to tone it down.

Maybe you get what I’m saying. Charles Péguy — the old poet, a hero of mine — wrote once that “Christianity in the modern world is no longer what it was — of the people … Socially it is nothing more than the religion of the bourgeois, the religion of the rich, a wretched sort of distinguished religion … that is why it means nothing.”

That’s exactly the sort of religion which tells you that you have a “right” to go unconfronted by whatever moral issue you want to exclude from your prayers simply by deeming it “divisive political messaging.” Whatever that is, that’s not Christianity. It’s more likely just nothing — comfortable prayers, but empty. And yes, I appreciate that is a quite damning thing to say.

But here’s the lesson, the hope: The moral power of Christianity cannot be bureaucratically managed. Archdiocesan officials, denominational leaders, conventions and conferences, whatever good they indeed do and whatever purpose they in fact serve, none of it determines or directs or stifles the God for whom they sometimes too confidently dare to speak. No organization, no vetted statement, can shield you from the God who has every right to disturb you and who probably should. The Spirit of God will not be managed.

The moral power of Christianity will not come by way of press conferences or podcasts but by protests and arrests, martyrdom maybe. And it will also sometimes come by way of obnoxious things like a Nativity scene you find offensive.

Our true prophets, you see, will rise from the streets, from those small communities, from churches and parishes willing to be disturbed, willing to disturb others. Because, of course, that’s where fear isn’t abstract, the fear of ICE and so much else.

Our bishops and other church leaders do and say many important things, but most people know only their local communities. Most people will never read some well-crafted ecclesiastical statement, much less some press release; yet they will see and immediately understand a Nativity scene that says “ICE WAS HERE.” And they will know thereby that God is with them.

Which, of course, is part of the Church’s task, to be brave enough to tell the oppressed that God is on their side.