It was just before midnight on the Saturday of Labor Day weekend when the phone started ringing. Dolores, a foster mother for migrant children in San Antonio, ignored it. The two Guatemalan teenagers she and her husband had been raising for months, Diego and Harry, were already asleep down the hall, and the retiree believed that no good calls came that late at night. But when the phone rang again thirty minutes later, Dolores relented and picked up. A government contractor with the Department of Homeland Security was on the line and told her that Harry and Diego needed to report to a local Office of Refugee Resettlement shelter right away. (The names of Dolores, Diego, and Harry have been changed to protect their privacy.)

Dolores didn’t want to wake the boys, but she was told she couldn’t wait, so she tiptoed to their room. As she stood amid their clothing, which was strewn over the floor, and their school supplies from a recent shopping trip, she didn’t know what to tell them. It took her a while to wake the boys and get them into the car. On the ride over, Diego and Harry were scared they would miss high school and were anxious about what would happen to them.

As is typical for unaccompanied minors apprehended at the border, Harry and Diego had been turned over months earlier by the Border Patrol to the Office of Refugee Resettlement, which placed them in detention shelters. Per a 1997 federal court settlement dictating that ORR release unaccompanied children to sponsors “without unnecessary delay,” the agency had worked to place the kids with host families.

After three months in a shelter, Harry had gone to live with Dolores. She described him as a little bit scared and homesick. Diego was placed with her after bouncing around facilities for six weeks. He was quiet and had a hard time adjusting to the new rules, she said: “Keeping his room clean, getting up early to go to school. He is always the last one to get ready.” The shelters had been nice enough—the boys were fed, had beds, and could enjoy common rooms with TVs, video games, and board games—but after they were released to Dolores’s family, they fell into a routine. Harry grew less worried; Diego started talking more. Now they relished the chance to live a more permanent lifestyle.

When the family arrived at the facility, there were still no answers to Dolores’s questions: Why did she need to drop the boys off? Where were they going? Who would be caring for them? “I ask [operators of the facility] what is going on, and all I see is tears in their eyes,” she recounted recently. “And I ask ‘Please, protect my children.’ ”

The boys were silent, eyes wide, as they were taken inside the facility. They entered a large conference room with around ten other children, some of whom lived in the building. They sat and waited.

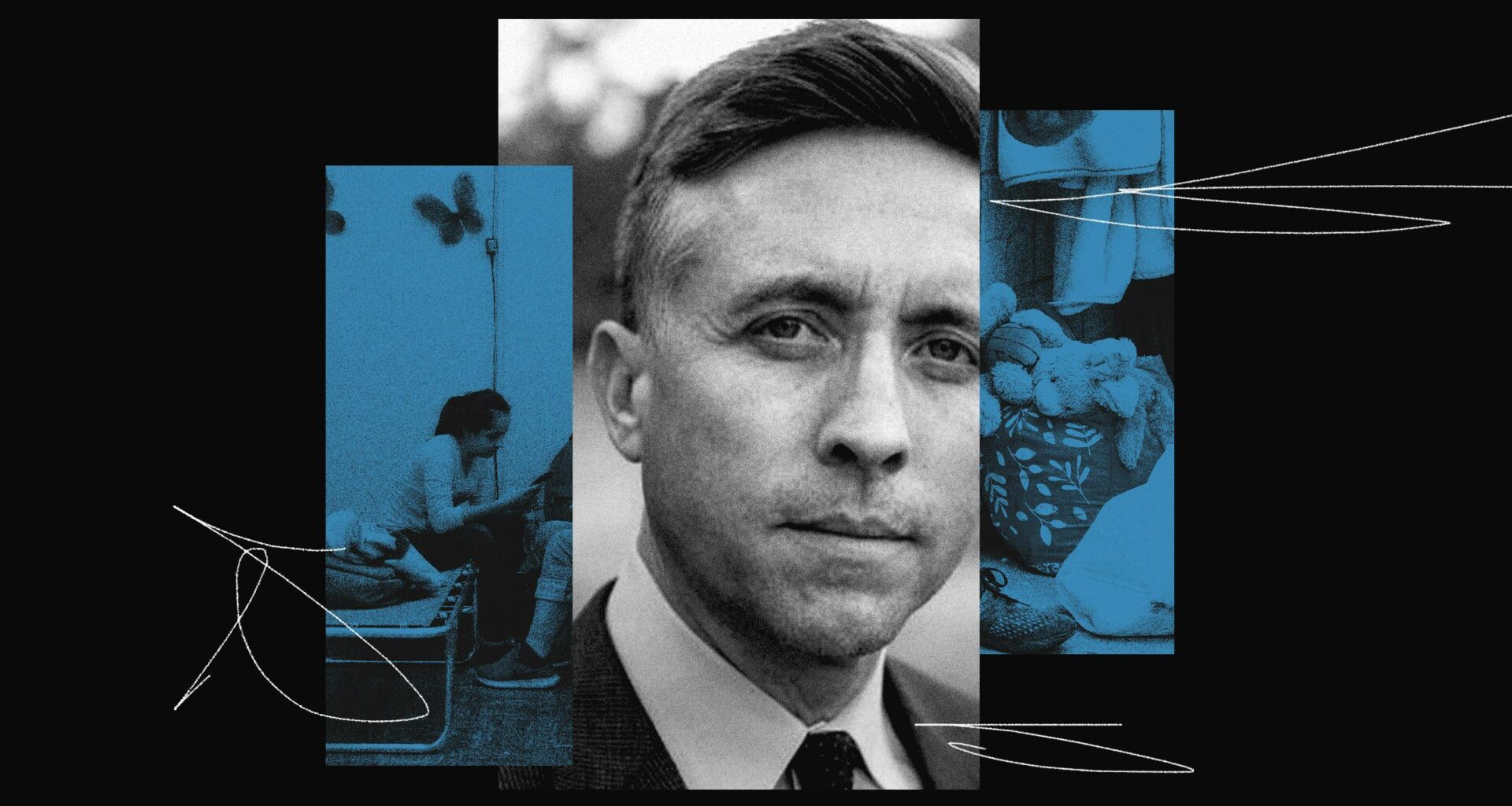

The man who would become their lawyer, Jonathan Ryan, a 48-year-old with a boyish face framed by white hair, was also in the facility that night. Ryan serves as the executive director of Advokato, a legal aid organization that, effective Labor Day, was slated to represent all the kids in five of San Antonio’s seven detention centers for unaccompanied minors. Ahead of assuming those legal responsibilities, Ryan had been working at home to set up the payroll system for his nonprofit when he was tipped off by one of the shelter’s staff members that the feds were collecting a group of detained and released Guatemalan children and planned to ship them back to their home country—a highly irregular government action. Ryan had rushed to his office on San Antonio’s northwest side to print out forms that the kids could sign to make him their attorney a few days before he formally assumed that role. Then he’d had to choose which of the seven shelters to go to.

“The clock was ticking, and I needed to decide which direction I was driving,” he told me. “I would only be able to go to one facility and [would have to] leave the others on their own.” Ultimately, he chose the largest campus, on the city’s West Side. Roughly a dozen children were gathered in a conference room, sitting in office chairs. Ryan saw Diego and Harry among them. He had met Diego earlier that week. What he remembered was a strong and confident teenager. What he saw now was a scared child.

Ryan got the kids’ signatures around 2 a.m., right before government buses pulled up to the facility to pick the children up. He tried to appeal to the bus drivers, telling them they were kidnapping kids in violation of the law and that “just following orders” logic would not hold up in court. His appeals were ignored. In subsequent legal filings, the Trump administration would argue that the separation of these migrant children from their families was a “tragedy” and that it had a responsibility to reunite them with their parents through repatriation. Justice Department lawyers would argue that parents had requested that their kids be returned. (The Guatemalan government would contest this, noting that the parents of 115 children in ORR custody had been contacted, and while at least 50 had said they’d be willing to welcome their kids back, none requested that they be sent back home)

Harry, Diego, and the other children were packed into a bus and driven to a tarmac in Harlingen, near the U.S.-Mexico border. There, the kids were loaded onto a plane. “The airplane started up. It was moving and started to get speed,” Diego recounted. He was terrified.

Before it could take off, however, the engines slowed and stopped. In D.C., a federal judge had ordered at the last minute that the children not be removed from the country until an emergency hearing could be held later that day. As the courts considered the matter, the kids were taken to shelters in Harlingen, where Diego and Harry remained for two weeks. Other children are still being kept there, according to Advokato.

Records show that Diego and Harry were 2 of 76 Guatemalan children rounded up nationwide that night. In twenty years of practicing immigration law, Ryan said he had never heard of anything like it—what he identified as the devolution of the already strained asylum process into lawlessness.

The next several weeks would only reinforce his sense.

Jonathan Ryan was born in Canada to Irish parents, but his family relocated to Texas when he was a child. Other than the time an expired resident card landed him in a Mexican jail while he was on Christmas break from the University of Texas law school, the now-naturalized U.S. citizen has spent all his time involved in immigration cases as a lawyer.

For twenty years, he has worked at various nonprofits representing adults, families, and children as they seek asylum in the U.S. He joined RAICES (Refugee and Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services) in 2008 and departed in 2021, founding Advokato the following year. When RAICES ended its subcontract to represent children in detention in Texas after government threats to funding, Ryan stepped in for San Antonio, a large hub, in August.

In eleven months, Trump has reshaped the nation’s immigration policy, particularly as it concerns minors. His administration has slowed down the release of kids from shelters to sponsors. According to government data, children spent an average of four weeks in a shelter during the 2024 fiscal year; this year they have been spending an average of four months. The prevailing message from the Trump White House has been that migrant children are being trafficked and that the government must protect them by keeping them in detention or sending them back to the home countries they fled.

When I visited Ryan weeks after Harry and Diego were shipped to South Texas, he sat in his nondescript office, furiously typing out text messages. His white-walled room was barren of personal effects or art. Ryan was trying to ramp up his staff and expected to spend $150,000 of his own money building the unaccompanied children’s program by November. Fifteen new, boxed laptops covered the small worktable in his office.

Advokato now represented more than 120 children from El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala, and he was struggling to keep up. He thought he would have time for day-to-day administrative organization building: hiring, ordering technology, buying office supplies. But he kept having to chase new immigration-policy developments. “I still need to sign my team up for immigration case-management software, but Jason keeps jumping out of the f—ing closet,” he said, referencing the villain of Friday the 13th.

That morning, Ryan learned about a new DHS proposal dubbed Freaky Friday. The agency was offering $2,500 to immigrant kids younger than fourteen to leave the U.S. Ryan called an emergency meeting in the break room turned office. Six staff members sat in a semicircle around an open laptop, from which five other employees stared back. The team planned out who would go to which facilities and outlined what they would say to their clients to ensure not to panic them.

Ryan looked around the room. “A month ago, this was me by myself getting this kind of news,” he said to the group. “As horrible as this is, I’m extraordinarily gratified to be here with all of you guys, and that you’re all here to help on this. It makes a big, big difference.”

In late September, Harry and Diego visited the office to speak with Ryan and fill out paperwork for their cases. They had spent two weeks in a shelter in Harlingen before being returned to Dolores. The boys were quiet about the experience, answering only in staccato phrases. They had been too worried to sleep much. There had been school instruction in detention, they reported, but it was simple and unconnected to what they were learning in San Antonio. They couldn’t go outside because it had rained most days.

Rather than wait for the previous legal-services provider to give Advokato the details of each child’s situation, Ryan’s team was redocumenting the conditions that had caused the kids to flee Guatemala, obtaining names and numbers of family members, and building cases that Ryan believed would have allowed the children to stay during the Biden administration years but might not now. Ryan peppered Diego and Harry with questions about their lives. They said they were grateful to be back in San Antonio and reported that their school was helping them catch up on the homework they had missed. They told Ryan they could finally sleep at night.

When the interview wrapped, Ryan stepped into the hall and gathered himself for a moment. He was left with just one thought about the children’s experience: “You have to try to do something this cruel.”

Featured image credits: from left: Eric Gay/AP; courtesy of Jonathan Ryan; Chandan Khanna/Getty

Read Next