Here’s a story about politics that might challenge your assumptions. It’s about the race for the U.S. Senate in Texas in 2018, the last blue wave, when a large chunk of the electorate was angry enough at Donald Trump to show up at the polls in numbers not seen in a midterm in the modern era. By the time voting locations closed at 7 p.m. in El Paso on November 6, the campaign staff of both Ted Cruz and Beto O’Rourke had reason to be anxious: O’Rourke because no Democrat had won a statewide seat in Texas since 1994, and Cruz because his opponent had conducted a ferocious tour of the state and raised more than twice as much money, amassing a war chest that might have made Genghis Khan jealous. Then, before ballots were tabulated, the total vote count of 8.3 million was recorded—a turnout of 53 percent that shattered the percentage in all midterms in the state since 1970. As a person familiar with one of the campaigns relayed to me years ago, one candidate began to celebrate.

If you’ve followed Democratic politics this century, you might expect that the ebullient candidate was O’Rourke. The Texas Democratic Party’s conventional wisdom for decades has been that nonvoters tend to lean toward it, and that a campaign that could convince enough unconscientious objectors to exercise their rights could win. The palliative comes with an oft-repeated punch line—“Texas isn’t a red state, but a nonvoting one”—that even O’Rourke has voiced.

But the candidate who cheered high turnout on election night in 2018 was not, in fact, Beto. The Cruz campaign knew that there weren’t 8.3-million-divided-by-two-plus-one Democratic voters in the state, so if turnout was that high, there was no way he could lose. (A spokesperson for Cruz declined to comment on the anecdote.) And of course, Cruz was right. He did win. It was the closest statewide election since the nineties, but this was not, as Democrats often argue, because O’Rourke activated masses of onetime nonvoters. The real magic trick of his campaign was convincing hundreds of thousands of Texans who also voted for Republican Governor Greg Abbott to support him simultaneously—not enough, but no small measure.

Old canards, however, die hard. As we approach another midterm election during a Trump presidency, another Democratic Senate hopeful is preaching the message that Texas is a secretly blue state. Announcing her bid for the Democratic nomination to run for Senator John Cornyn’s seat last week, Congresswoman Jasmine Crockett addressed “the haters in the back” of the South Dallas venue and explained how she could win a statewide seat though no Democrat had in three decades. “So they tell us that Texas is red,” she said, pausing, first as laughter erupted, and then to snicker herself. “They are lying,” she said, “We’re not. The reality is that most Texans don’t get out to vote.”

I was not there, but allow me, for a moment, to assume the role of Hater in the Back. Crockett’s claim is, bluntly, wrong. Texas is indeed a nonvoting state. Those who are eligible to vote but abstain have outnumbered those who turned out for the highest vote getter in every Texas election this century. The specific electorate changes every cycle, but as a group, the nonvoters are disproportionately young, poor, and Hispanic—three demographic segments Democrats have long assumed are likely supporters. Part of the reason some Texans don’t vote are voter suppression laws that make the state one of the toughest to cast a ballot in. But Texas is a red state because those who don’t vote, or who don’t often vote, are not, as a bloc, Democrats-to-be.

In 2022, when I asked dozens of local election officials, pollsters, political scientists, and political operatives for their estimates of the nonvoting population’s partisan allegiance, there was bipartisan consensus on the skew. The Texas Democratic Party’s model estimated about 56 percent of 2018 nonvoters were Democratic leaning. A GOP operative told me that lined up pretty well with his party’s estimate given its voter file, which modeled nonvoters by their consumer habits. (Do they shop at Cabela’s or Whole Foods? Subscribe to Garden & Gun or have a Sierra Club membership?)

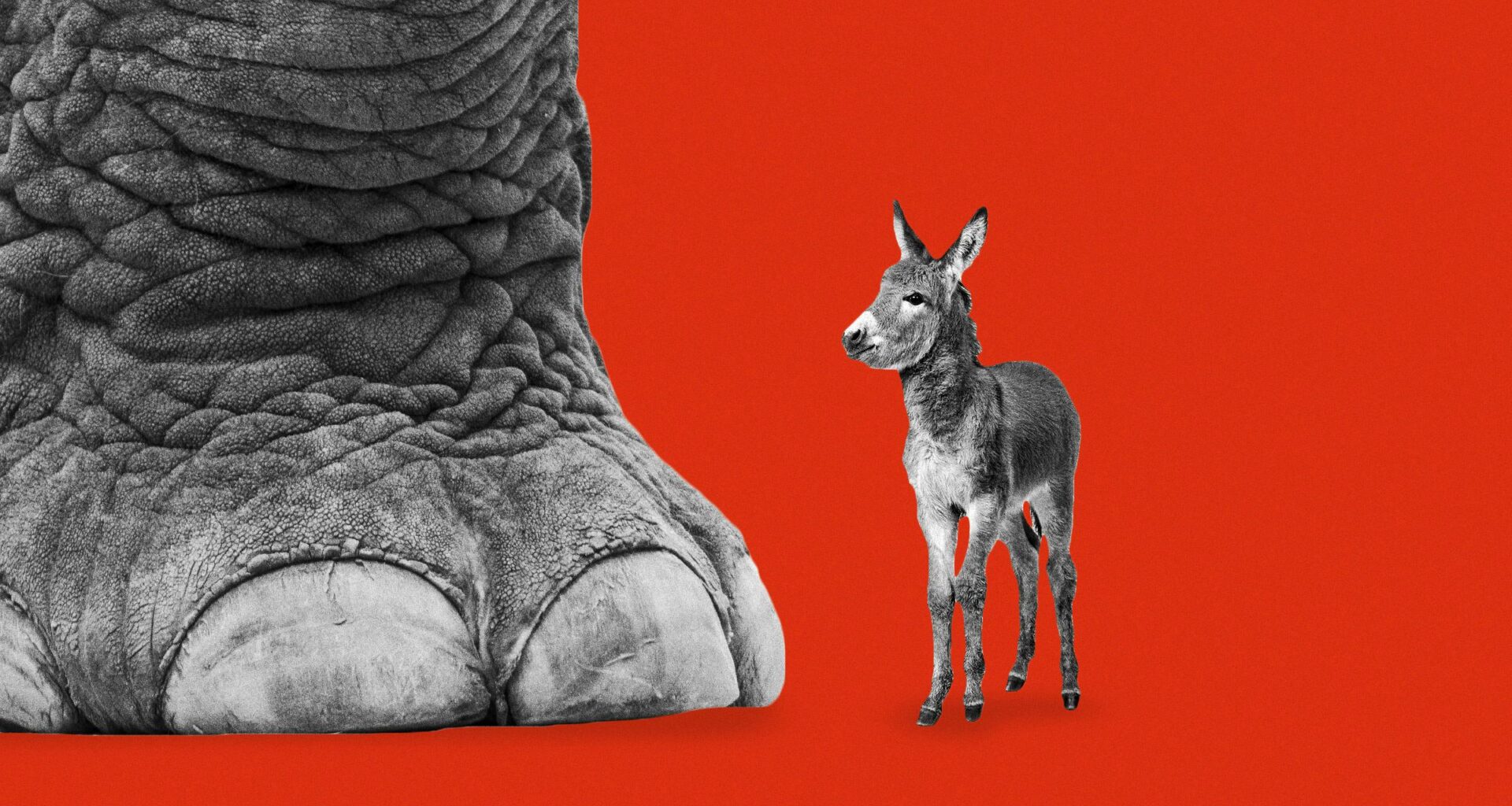

Sorry, Democrats, Texas Is Not Secretly a Blue State

Sorry, Democrats, Texas Is Not Secretly a Blue State

To make up the large advantage Republicans have among existing voters, Democrats need to either drive huge numbers of those nonvoters to the polls while Republicans don’t or convince GOP-leaning voters to support them. Many campaigns try to do both, including that of Crockett’s primary opponent, state Representative James Talarico. JT Ennis, a spokesperson for the campaign, told me, “Ending thirty years of one-party rule in Texas requires a campaign that energizes the Democratic base, turns out new voters, and welcomes Trump voters who are now feeling conned.”

I asked Crockett about the balance of her strategy. “Nearly half of Texans don’t cast a ballot. Many feel that nothing ever changes or that their vote doesn’t matter. Frankly, too many politicians have relied on the same tired playbook of politics as usual,” she wrote. “By speaking directly to our shared realities, being unafraid in my advocacy, and unapologetic in my service, I’m earning the trust of a broad cross-section of Texans.”

When it comes to the turnout approach, there is no recent evidence, despite high-profile and expensive efforts to do so, that the Democratic party can outperform the GOP in getting nonvoters to the polls. Take the 2020 election, for example, the best turnout operation Democrats have ever run. That year, when there was a presidential race between Trump and Joe Biden, and Cornyn was last up for reelection, the party went all in on a strategy to activate low-propensity voters, those who are eligible to cast ballots but rarely do so. The state party invested a large chunk of its $25 million coffers into a voter model, which assigned each Texan a partisanship rating and a likelihood-to-vote score, based on prior electoral history. For those who were eligible to vote but had not registered—a number leaders said totaled 5 million (likely a twofold overestimate, which you can read more about here, and one Democrats have subsequently lowered)—the party estimated as much as 75 percent leaned Democratic. And then the party contacted all it deemed future Democrats.

Meanwhile, Republicans also saw fertile ground among the nonvoters. Steve Munisteri, the former party chair who had left Texas in 2015 to work for Senator Rand Paul and then for the Trump White House, returned to the state to assist with Cornyn’s reelection campaign and to help lead a turnout operation with Karl Rove, the electioneer who turned Texas red in the nineties. They focused some on the unregistered but eligible, setting up registration efforts outside places where Republicans gather, including Trump rallies and gun shows, and getting more than 200,000 Texans added to the voter rolls. (In Texas, voters don’t register by party, so the partisan allegiances of those they registered are unknown, but given where they were registered you can get a pretty clear idea.) They focused more heavily, however, on the 7.4 million Texans who were registered but hadn’t voted in 2018, targeting the 3 million the GOP’s voter model had flagged as likely Republican.

Unprecedented numbers of low-propensity voters went to the polls that year: The election in November was the highest turnout election by percentage since 1992, with 11.3 million of the state’s 17 million registered voters casting ballots. And Republicans swept every race—because infrequent voters in the state aren’t de facto Democratic ones.

In a postmortem report, the Democratic party noted that, according to its model of voter likelihood, Republicans were more successful at getting low-propensity voters to the polls. They were also better at getting new registrants to show up: While Democrats registered 150,000 more Texans than Republicans did, the GOP got 26,000 more people who were freshly eligible to vote to actually vote.

Why might that be? In 2022, I drove 1,454 miles, crisscrossing the lowest turnout counties in Texas, one of the lowest turnout states in the country, looking for nonvoters who could help provide an answer. I ignored the old wisdom to avoid discussing politics with strangers and spent days outside convenience stores, grocery emporiums, and dive bars asking whether folks planned to vote or not. The majority response was not yes or no. It was “What election is there?”

Many I met were lapsed but devout Republicans, voters who cared deeply about the oil and gas industry and gun rights but didn’t feel either were at risk and thus didn’t need to defend them. But I also met dozens of one-time Democrats who had suffered crises of faith and believed their votes didn’t matter enough to bother casting. Locally, these nonvoters told me, Democratic politicians who won accomplished nothing–streets remain unpaved, flood zones unprotected. At the state level, their candidates almost always lost, owing largely to the state’s gerrymandering; when they won, they couldn’t affect change in GOP-controlled Austin. Federally, some said, their votes didn’t count—Texas always went red anyway.

I met less cynical likely Democrats who told me they weren’t voting because no candidate had sought their vote, despite O’Rouke focusing heavily on turnout during his bid that year for governor. At the Reeves County Library in Pecos, I chatted with the receptionist, Mariana, beside a credenza where stacks of primary-election voter guides remained untouched, months after that election. Mariana was a college student who told me that her biggest concerns were the environment and gun control, and that she was on the “Democratic side of things.” But, even as O’Rourke, who famously vowed to seize citizens’ assault weapons, campaigned for governor, she insisted she wouldn’t vote for him. She explained she didn’t “know enough about the candidates” since “no one had reached out.” It’s unlikely any Democratic campaign would: Activating reticent voters is costly, and the party focuses most of its spending in large cities, where money goes further.

Democrats might see opportunity in Mariana’s story. Might Crockett, if she wins the party’s nomination, do a better job reaching out to those just waiting on a Democrat to care about them? Can she spend on those efforts better than Beto did with his massive campaign coffers?

Dewey did not defeat Truman, so I’ll hold off on predictions. But here’s another telling anecdote—this one less surprising. The day Crockett launched her candidacy, Derek Ryan, a former data whiz for the Republican Party of Texas, reported on X that at least one voter who hadn’t cast ballots for Democrats recently had been reached with a text requesting support and a donation. That voter was his wife, who had voted in eight straight Republican primaries.

Read Next