With drought conditions growing across Maine, some farmers are feeling the burn as the soil dries up.

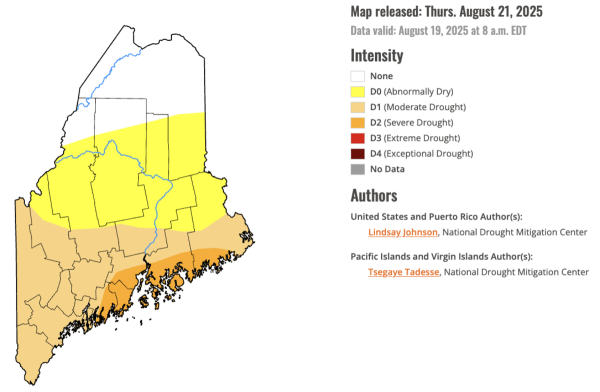

Three-quarters of the state is in danger, with abnormally dry conditions in central portions to moderate or severe drought farther south, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor.

“Flash” drought conditions have hiked fire danger statewide and are affecting some vegetable and fruit crops. Potatoes, for instance, need healthy moisture to bulk up. But Caribou has recorded less than an inch of rain this month, according to the National Weather Service. Parts of Aroostook County are still in the “no drought” range, yet vegetation is turning brown and dust rises from fields.

Drought is here, and it’s burning things up at a crucial stage, just before harvest, seed potato grower Daniel Corey of Monticello said.

“We’re drying up. Right now the crop’s hurting,” Corey said. “By the middle of the day, [plants] are struggling, they’re drooping, and it’s just bone dry underneath.”

So far this month, Caribou has received 0.87 inches of rain, about 1.5 inches below normal, according to the weather service. Frenchville recorded 0.8 inches, 1.7 inches below normal. Houlton has gotten 0.4 inches, nearly 2 inches less than normal.

Farther south, Millinocket is also 2 inches below normal, having gotten only half an inch of rain, and Bangor is at half its normal monthly rainfall at 1 inch.

The most recent drought conditions in Maine were issued today by the U.S. Drought Monitor. Credit: Courtesy of U.S. Drought Monitor

The most recent drought conditions in Maine were issued today by the U.S. Drought Monitor. Credit: Courtesy of U.S. Drought Monitor

Potato plants use the most water in July and August when growth is at its highest, University of Maine Cooperative Extension scientists said in an irrigation bulletin. Too little moisture can reduce size and yield. Irrigation can lessen the effects of drought.

An Aroostook log from the University of Nebraska’s National Drought Mitigation Center reported many farms are irrigating nonstop as conditions have gone from mildly to moderately dry. Leaves are wilting and yields could be affected.

Daniel J. Corey Farms grows 1,000 acres of potatoes in Island Falls and in the Monticello/Houlton area. Though northern Aroostook got about an inch of rain Sunday, southern Aroostook saw only about 3/10ths of an inch, Corey said. It wasn’t enough.

The whole Northeast is dry, he said. He’s talked to farmers in other states and Canada, and one from Prince Edward Island told him it was their driest season in a decade.

Corey’s operation is irrigating with everything it has, he said. They have three or four pivots going, but that can only cover about 20 percent of the crop. And as the growing season winds down, the lack of rain is likely to affect tuber size.

“The calendar’s telling me I’ve got to kill [tops], and the [potatoes] are not quite the size I want them to be,” he said. “But I can’t wait for the rain. The calendar’s pushing us.”

Parched earth is also affecting vegetable gardeners, as well as Maine’s number-two food crop, blueberries. Canada feels it, too, and its blueberry crop could decrease by about a third this year, an industry spokesman said in the trade publication Fresh Plaza.

On the other hand, Aroostook grain crops are faring better, because most of their growth occurred earlier, when rain was more abundant.

“We got rain when we needed it, and this dry weather lines up with when the grain needs to dry,” Caleb Buck of Buck Farms in Mapleton said.

Buck Farms grows about 1,800 acres of barley, wheat and oats, along with mustard and field peas.

As they’ve examined this year’s crops, they haven’t seen effects of dryness. The quality so far looks good and is comparable to that of past years, Buck said.

Though Maine escapes tropical heat, it faces weather unpredictability, such as excess moisture and drought, University of Maine potato breeding program director Mario Andrade said in 2003. The program works to create potatoes to withstand pests, disease and climate stresses.

Much of the work is done at the Aroostook Farm in Presque Isle, and a new research lab will help as technicians use drones, advanced imaging and even DNA science to observe and predict what varieties will fare best in a changing climate.

But no one can predict the vagaries of Mother Nature, which growers like Corey know all too well. Two years ago, a wet growing season had farmers on edge. Now they’d likely give an arm for rain.

Drones are among the new technology that the Aroostook Farm in Presque Isle will use to help scientists gather detailed images of potato test plants. University of Maine doctoral student Salem Ermish (right) demonstrates the drone, while Diane Rowland, dean of the College of Earth, Life and Health Sciences, looks on. Credit: Paula Brewer / The County

Drones are among the new technology that the Aroostook Farm in Presque Isle will use to help scientists gather detailed images of potato test plants. University of Maine doctoral student Salem Ermish (right) demonstrates the drone, while Diane Rowland, dean of the College of Earth, Life and Health Sciences, looks on. Credit: Paula Brewer / The County

Some relief could be on the way, with showers in the forecast for much of Maine on Monday. Whether that happens or not remains to be seen.

“Welcome to my world,” Corey said.