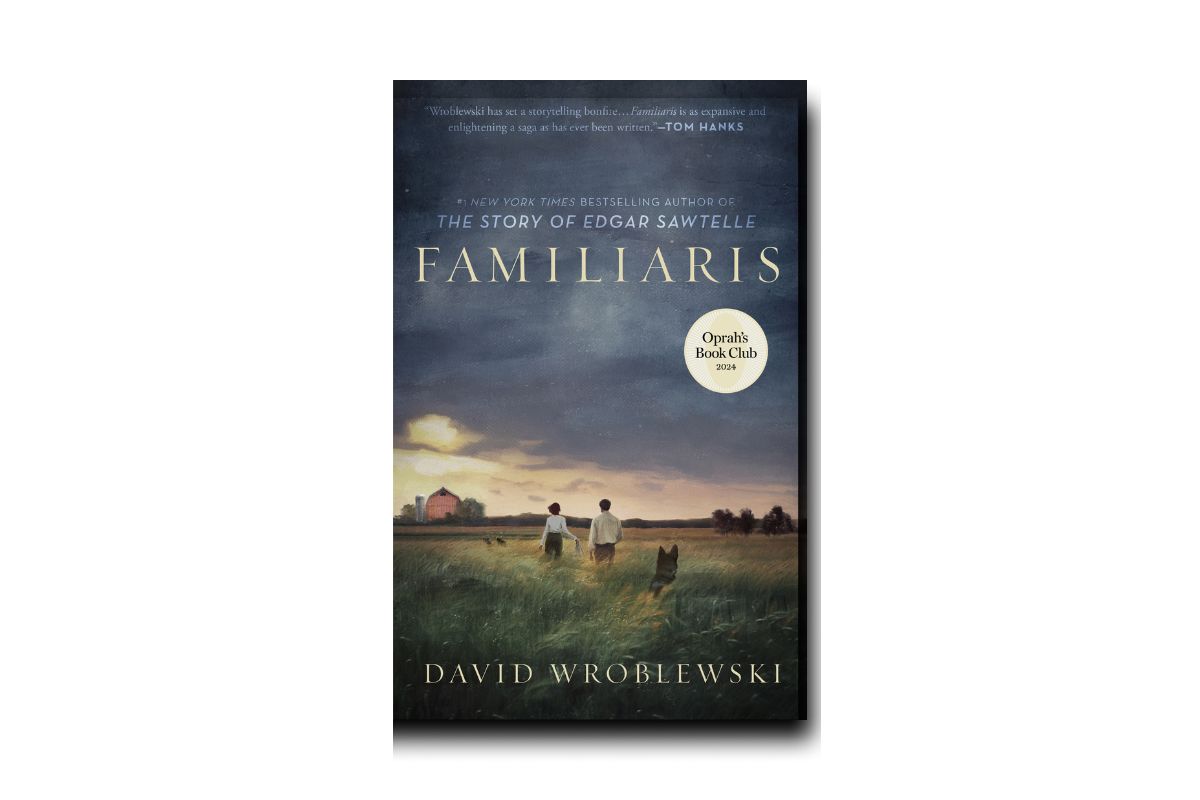

This book won the 2025 Colorado Book Award for Novel.

A memory: slouching behind his desk at the back of Miss Diffy’s fifth-grade classroom, hot, underoxygenated, cartilaginous. The stifling afternoon heat, the hazy October sunlight, and the drone of Miss Diffy’s voice have combined to form the anesthesia of the Deadly Poppies, which dropped Dorothy like a shot buffalo in Oz. A surf beats against his eardrums, words drift from Miss Diffy’s mouth like dandelion cotton, his eyes survey the innards of his head.

Through the simple act of standing at her desk and reading aloud, Miss Diffy can halt time. It is six minutes past two o’clock, and it has been every time he’s looked for the past hour. Now John is drowning, slipping beneath the waves of an Atlantic of lassitude, wishing something, anything, would happen worth swimming another stroke for.

UNDERWRITTEN BY

Each week, The Colorado Sun and Colorado Humanities & Center For The Book feature an excerpt from a Colorado book and an interview with the author. Explore the SunLit archives at coloradosun.com/sunlit.

Prospects: not good. Miss Diffy intends to read aloud every single word of “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” having announced that the narrative never fails to awaken her students’ imaginations.

The tale itself isn’t bad: timid schoolmaster, Headless Horseman, etc. Marvelous, in fact. But John has read it for himself already, and whatever gift Miss Diffy once had for the oral interpretation of fiction fled her body eons ago, along with the color in her hair and the pigment in her skin.

Only a miracle can save him now. It is too much to hope for, yet one occurs: Kenny Flanagan in his front-row desk sits up ramrod straight and clamps one hand over his mouth. The other hand rockets into the air. Miss Diffy reads on. A spasm passes through Kenny Flanagan’s body. He pulses his splayed fingers four or five times. Miss Diffy reads on. Finally, Kenny stands and removes his hand from his mouth just long enough to announce that very soon now he expects to throw up.

This is not because Kenny Flanagan’s imagination has awakened. Kenny Flanagan’s imagination has been hibernating in a small cave in a riverbank near the bottom of his spinal cord, munching scraps and bones of memory, and it will remain in hibernation for as long as John Sawtelle knows Kenny. (Though, as John will later reflect, if a person’s imagination were to suddenly awaken after a lifetime’s absence, vomiting wouldn’t be entirely inappropriate.) No, Kenny Flanagan expects to vomit because the bologna sandwich he ate at lunch had spoiled in the warmth of the Indian summer morning.

“Familiaris”

>> READ AN INTERVIEW WITH THE AUTHOR

Where to find it:

SunLit present new excerpts from some of the best Colorado authors that not only spin engaging narratives but also illuminate who we are as a community. Read more.

Miss Diffy’s fifth-grade classroom consists of one sorely distressed teacher’s desk, one dusty blackboard, one long wooden pointer tipped with black rubber, which Miss Diffy whacks across the fingers of young Visigoths, and—her pride and joy—a globe on a four-footed pedestal, encircled by two hinged brass hoops upon which latitude and longitude markings are engraved.

Kenny Flanagan follows his pronouncement with a peristaltic burp. Now time snaps to full flow.

But children have been throwing up on Miss Diffy’s desks since the dawn of mankind, and by gauging his gulps and swallows she can determine with great accuracy how much time remains with which to maneuver him to the nurse’s room. She sets her book on her desk, marks the page with a length of green ribbon, and steers Kenny to the doorway.

There she pauses to survey the classroom. Kenny urps and staggers in place beside her. He cannot believe Miss Diffy has stopped. His legs churn with desire; he is a sled dog in harness, bounding at the traces.

“Class,” she says, the crispness of her voice surprising for a woman who moments earlier had been practicing hypnotism. The tonnage of her gaze comes to rest on John. “Johnny will take up reading the story where I left off. Johnny, if anything is out of order when I come back, I’ll be holding you responsible. Is that understood?”

John stands. He nods solemnly. “Yes, Miss Diffy.”

“You may stay in your seat,” Miss Diffy says. She sets the tip of her index finger between Kenny’s shoulder blades and the class listens as their duet of footclops and strangled retching recedes down the hallway. John opens his textbook. They are at the part of the story where Ichabod Crane flees the Headless Horseman.

“Just then he heard the black steed panting and blowing close behind him,” John intones, with as much drama as he can summon. “He even fancied that he felt his hot breath.”

This elicits a giggle from Eunice Avery, whom John has a crush on, and Eunice’s giggle makes him daring.

🎧 Listen here!

Go deeper into this story in this episode of The Daily Sun-Up podcast.

Subscribe: Apple | Spotify | RSS

He stands. All eyes are upon him. Ichabod Crane’s horse is rushing over the bridge. John walks up the aisle, still reading, until he reaches the front of the classroom. He spies Miss Diffy’s globe resting in its latched cage, and hoping to illustrate the story for greater effect, releases the latch, unhinges the brass cage, and deftly pops out the globe. A brass nub projects from the north and south poles where the longitudinal hairlines converge. Its surface is shellacked paper; he can feel the slight ridge where one edge of the papered surface meets another at the equator. He clamps the globe to his side, Europe ribward, as if it were the Headless Horseman’s rogue head, and holds his book with his other hand.

A large, quiet boy sits in the front row, gaping—possibly at the story (which is certainly gape-worthy, John thinks). Or possibly at John’s disregard for Miss Diffy’s most valued possession. Or—and this idea pleases him—as a result of John’s oratorical skill. Each time John looks up from the page, the boy still gapes, a drop of spittle quivering on his lip and his eyelids hovering over his pupils as if he is watching a motion picture inside his mind, seeing Ichabod Crane race in terror across the bridge as the Horseman flings his very own head at the galloping schoolmaster.

“Ichabod endeavored to dodge the HORRIBLE MISSILE,” John reads, pouring on the drama, “but TOO LATE! It encountered his cranium with a TREMENDOUS CRASH—he was tumbled headlong into the dust, and Gunpowder, the black steed, and the goblin rider, passed by . . . LIKE A WHIRLWIND!”

What John does next is not premeditated. It’s a case of one thing leading to another. The boy’s mouth is an oval of mesmerization. John slides his hand around and under the globe until it balances on his palm; it’s the size of a pumpkin more or less, and very light for a planet. John pauses for the briefest moment to note the stupidity of what he is about to do. Then he lofts the globe into the air.

The boy shudders in his chair like an electrocuted frog, but his hands fly up and he catches the cephalic globe.

The class gasps, then bursts into cheers.

“Quiet,” John says, severely. “They’ll hear.”

Whatever possessed John to walk to the front of the classroom was strange; stranger still was his impulse to pitch the globe like the Horseman’s head to this boy, whom everyone called by his last name, Elbow, and who is now fully awake and contemplating the globe with something like awe. But strangest of all is the idea suddenly taking shape in John’s mind.

In later years John will come to regard his imagination as, at best, semidomesticated: contained by him but not entirely of him; an animal captured in a circus wagon, sleeping when he most wants it to wake, pacing and fretting and thrusting its head through the bars to howl when he dearly wishes it would curl up and sleep. And those times when the animal breaks the bars to run loose, he will struggle not to kiss women he doesn’t know; tell beautiful, needless lies; and dance in the aisles of grocery stores to melodies playing only in his mind.

But that is the future. Right now, in Miss Diffy’s classroom, John’s gaze keeps returning to the empty brass hoops atop Miss Diffy’s globe stand. Wouldn’t it be interesting (howled the animal, bending a pair of cage bars) if a head took the place of the globe? A head—in the globe cage!

That’s silly, John thought. But the animal circled and stalked and demanded and bellowed: How wonderful if a head were to replace the globe! How excellent! How beautiful!

How dopey, John thought. How stupid.

NEVERTHELESS! the animal roared.

So that was one factor.

Another was the tangible, though unspoken, encouragement of his audience. His classmates had been amused by his reading, intrigued by his journey up the aisle. But even before he’d reached the front of the classroom, the story still pouring from his mouth, he’d felt their interest beginning to wane, and some part of him despaired. Here went time, oxidizing the luster on every novelty: a boy reads, a boy stands, a globe breaks free of its cage. Old Elbow’s goofy gasp is the jewel of their day. Then it is browning with ordinariness like a peeled apple.

Seventeen children sit looking at him. More, their gazes say. Something new. Astound us. Outrage us. We have nothing to lose by watching.

David Wroblewski is the author, most recently, of the novel “Familiaris,” his followup to the international bestseller “The Story Of Edgar Sawtelle.” He received an MFA in Creative Writing from the Warren Wilson MFA Program for Writers, and a Bachelor’s degree in computer science from the University of Wisconsin. He lives on Colorado’s Front Range with the writer Kimberly McClintock and their dog Luci.