The posters advertising the International Rice Festival in Crowley, like countless others created for agricultural festivals across South Louisiana, are popular collectors’ items, showcasing Louisiana life in all its porch-jamming, kitchen-dancing, crawfish-boiling beauty.

Their releases are usually moments of big celebration. But not this year. When the design for the 88th International Rice Festival hit social media, it was slammed as “AI slop,” web slang for generic and increasingly ubiquitous images created with AI tools.

“This is not ‘art’ it is AI,” one comment read. “This does not reflect Louisiana artists. There are so many local artists that work hard to make beautiful, original art. Very sad to see this is the one that was chosen.”

The design, critics said, lacked the soul and color of previous posters and, anyways, the grains looked more like wheat than rice. The Rice Festival organizers quickly began moderating comments, likely hoping to hem in the controversy, which had already metastasized to other social media platforms.

There’s a marked difference between the colorful posters of Rice Festivals past and this year’s understated, monochromatic design. And the panicles do lack the characteristic bend that makes rice grains easy to identify.

But was it AI that brought Crowley the poster that, opposing the critics, some called “beautiful,” “absolutely gorgeous” and the “best poster in a long time”?

Well, yes and no.

The poster was created by a local artist, Cris, who asked to be identified only by her first name and her professional moniker, ZEPPIX, out of concern for her own and her family’s privacy.

The controversy took the single mom, photographer and visual artist by surprise. She had only recently gotten back into visual arts, mostly digital, after spending years focused on photography. And while she admits to using an AI tool called Midjourney for parts of the design, she argues that this doesn’t mean she didn’t work on it.

“There’s so much handwork that went into that,” says Cris, from the overall composition to making changes throughout the process on a tablet she uses for original drawings and other digital art. he may have used a variety of tools, but that doesn’t mean the poster isn’t the product of a local artist, she maintains.

According to her, the organizers agreed. “They knew that it came from different sources — they didn’t care,” Cris says. Creating the poster, a digital product as it may be, still involved lots of back and forth between her and this year’s festival president, Julian Leblanc, she notes, implementing his feedback and wishes into the design.

Leblanc stands by the design. “As it stands now, that’s my poster,” he told The Current on Friday, declining to comment further.

The controversy tapped into a broader concern that goes beyond the Rice Festival or its counterparts celebrating ducks, oysters, shrimp and petroleum. AI, many fear, is automating artists out of work and dehumanizing art in the process.

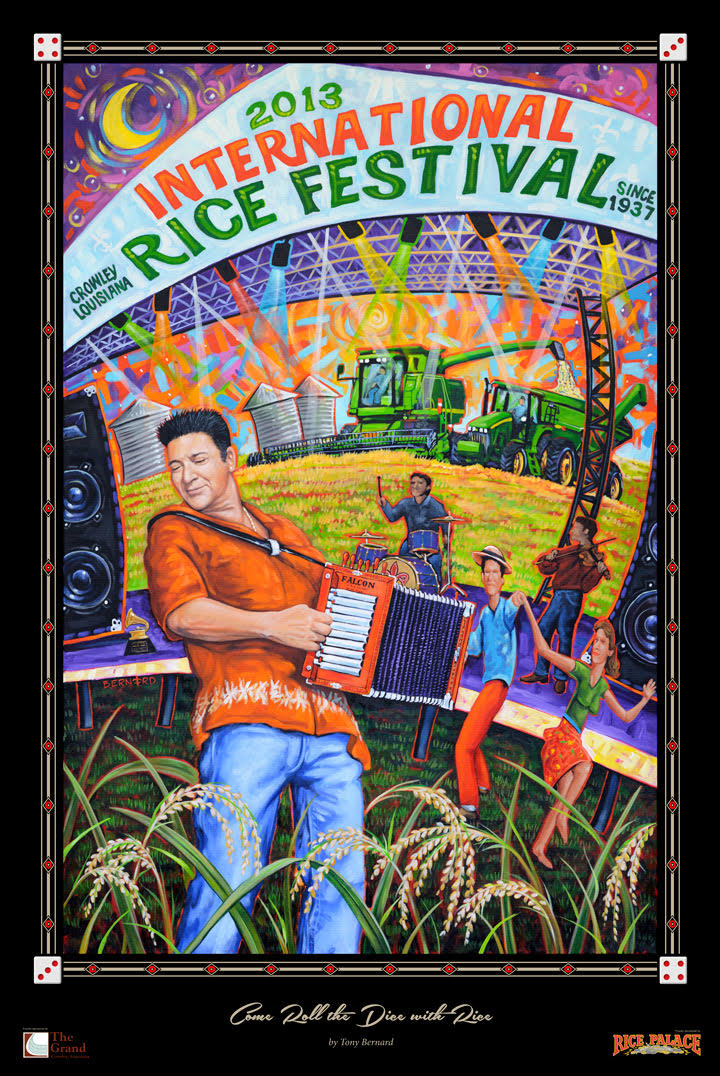

Tony Bernard, who has created multiple Rice Festival posters, works with acrylic and canvas. Image courtesy of Tony Bernard Studios

Tony Bernard, who has created multiple Rice Festival posters, works with acrylic and canvas. Image courtesy of Tony Bernard Studios

“I don’t think it affects artists that are already established,” says Tony Bernard, a Lafayette artist who trained under George Rodrigue and has painted dozens of posters for festivals across South Louisiana, including several advertising the Rice Festival. “But people that are younger and trying to get their foot in: I think it’s a slap in the face to them.”

While at their core commercial products the posters — often characterized by their decidedly imperfect technique — bear cultural significance as visual representations of Louisiana’s unique culture. The controversy poses a philosophical question: What makes art, art?

“Art is more than just painting. It’s composition, and it’s ideas,” Bernard says. “Well, AI don’t have ideas.”

That’s debatable — AI tools have become infamous not just for what they know but what they hallucinate (recipe for delicious spaghetti with gasoline, anyone?) — but Cris argues that it’s her and Leblanc’s ideas that dominate the poster’s design.

LeBlanc wanted to pay tribute to Lt. Allen “Noochie” Credeur, the Rayne police officer who was shot and killed by friendly fire in March. So Cris worked his badge number into the design. Should the poster feature a tractor or a combine? The two debated and settled on a tractor. The accordion placed prominently on the poster had to be a traditional Falcon brand, she decided.

“Every single freakin’ aspect,” Cris says. “It was not easy, it took many hours. It took months.”

Still, she says she understands her critics’ concerns. “I see their side, I do,” she says. After years of competing for the commission, she was just happy to be chosen this year — a sense of joy that has been dampened by the harsh online criticism. Still, she says she wouldn’t do anything differently if she could — despite her respect for visual artists who work with a brush and canvas.

“Please don’t take it personally and try to break me down because y’all think I’m hurting other artists,” Cris tells her critics. “Nobody’s ever going to stop buying hand-drawn art.” And while she sees herself hanging art generated with AI tools on her own walls, she doesn’t see it replacing more traditionally created pieces in her home either. “Nothing’s ever going to top that,” she says.

After receiving the slew of criticism she did, and almost wanting to delete her online presence over it, she has a message for whoever throws their hat in the ring next. “Whoever does next year’s [poster] better be real confident,” she cautions.