Few technology announcements have been met with such a mixture of humour, melancholy and memories than AOL’s recent revelation that it would be discontinuing its dial-up internet service.

Many were understandably surprised to learn that AOL still offered the dial-up service, and the news inevitably elicited memories of the loud but charming modem dial-up sounds that accompanied it.

Even in many remote parts of the world, where broadband infrastructure is non-existent, dial-up internet has been largely shunned in favour of 5G cellular technology and low-earth-orbit satellite services such as Starlink.

So how did AOL keep its dial-up service going for so long? The short answer is that although it might be difficult to find users, some still do rely on the service, or at least want to keep it handy. According to data from the US Census Bureau, about 163,000 households in the US still depend on dial-up internet, and it’s safe to say a portion of that number used AOL.

There are a few factors leading to this, paramount among which is that despite widespread broadband availability, there are still rural areas of the US that have no high-speed access. The same goes for parts of Canada. Economics also plays a role, with dial-up services still much cheaper than broadband.

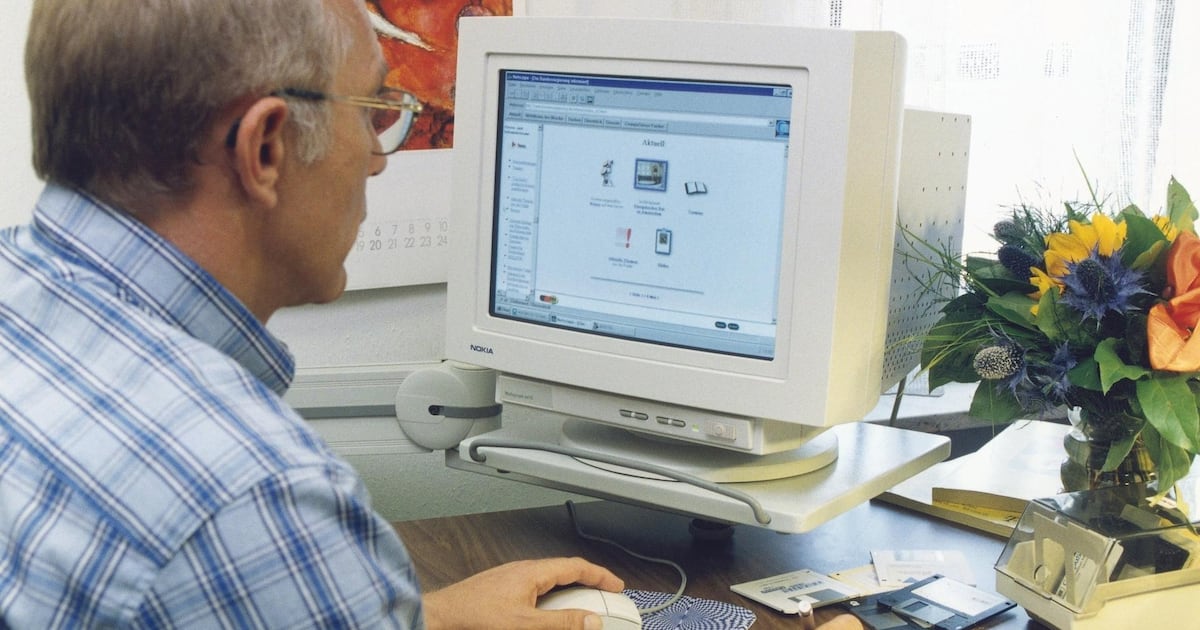

And although few statistics are readily available, the population of dial-up users probably skews older, with that demographic probably using the internet for basic email and no-frills web browsing that don’t require fast downloads.

Some dial-up customers may simply have forgotten to cancel their service or have died. Whatever the scenario, that steady stream of monthly income – often referred to by economists as recurring revenue – proved to be comfortable for AOL, until it wasn’t.

“AOL routinely evaluates its products and services and has decided to discontinue dial-up internet,” announced the company, now owned by Yahoo. “As a result, on September 30, 2025 this service and the associated software … will be discontinued.”

Steve Case, once the media darling and rock-star chief executive leading AOL through its most prosperous days in the mid-1990s, joined a chorus of people reminiscing about the service. “Thanks for the memories, RIP,” he posted to X.

Robert Wahl, an associate professor of computer science at Concordia University Wisconsin, said that although dial-up has largely outlived its usefulness, the sheer number of those who first logged on to the internet using it means it is seared it into the collective memory.

“In its day, one of the huge advantages was that if you had a phone line, you had internet access available,” he said, referring to the built-in advantage that gave dial-up such a long shelf life. “However, these advantages are often outweighed by the extremely slow speeds of dial-up access,” Prof Wahl explained. “Dial-up systems were also hampered by the fact that an incoming phone call on the same phone line could drop the internet connection,” he said.

Hypothetically, users might still be able to use dial-up modems to communicate and use obscure networks, but with AOL’s announcement, one of the last pillars of the original internet boom has finally come crashing down.

It’s easy to forget now amid almost ubiquitous broadband internet access, 5G cellular technology and, soon, 6G, but AOL, along with other dial-up services such as CompuServe and Prodigy, were the first experiences many had using modems. The services gained popularity around the same time as the World Wide Web, as it was often referred to originally (largely the idea of Sir Tim Berners-Lee), was gaining traction.

A debate emerged amid all these digital communication developments about which philosophy would prove victorious. AOL, CompuServe, Prodigy and others took walled-garden approaches, putting a user-friendly interface on the back of dial-up modem connections where people would check email and stocks, use chat rooms and browse a few headlines.

AOL soon became the most popular choice, in part thanks to an unprecedented advertising blitz in which the company gave away its software on free CDs. At one point in the 1990s, it became almost impossible to avoid seeing AOL logos and discs.

Meanwhile, there was also sudden interest in early web browsers such as Mosaic, and later Netscape Navigator, along with Internet Explorer, that often sat on top of the dial-up services. Yet gradually, upgrades were made to the US telecoms grid, and high-speed broadband internet services began to pop up.

The speed difference compared to dial-up modems, and the fact that it was almost “always on”, opened the floodgates and made broadband popular, leading to an easy victory for the technology. Web browsers, which were increasingly sophisticated and easier to use, combined with the simplicity of Hypertext Markup Language (HTML), also became more prevalent and important.

Perhaps most importantly, because web browsers weren’t walled gardens like AOL or similar services, they were easily decoupled from those services, ultimately rendering them unnecessary. Yet as US Census Data points out, someone, somewhere is still using dial-up.

Believe it or not, even with AOL’s demise they still have options. Juno and NetZero offer the service, promoted on their incredibly simple and presumably fast-loading websites, which are designed for 56k modem speeds.

“We offer reliable service with thousands of dial-up access numbers nationwide,” reads NetZero’s homepage, a charming pitch to prospective customers that elicits memories of the web’s earliest days. Over on Juno’s page, it offers “up to 10 hours a month of reliable dial-up internet access, free of charge”.