The annual Hawaiʻi Conservation Conference typically covers all things climate- and environment-related in the islands, with sessions modeling varieties of animal trapping technology or discussions of invasive species research.

This year, participants who walked into the Hawaiʻi Convention Center’s Room 312 after lunch on the second day were greeted by a woman behind a table with markers, colored pencils and pieces of scrap paper.

“Are you in the right session?” she asked some of them. “Grief?”

As deep anxiety over climate change and the future grips the general public, this summer’s conference featured a first-of-its-kind grief seminar. The session, moderated by Danielle Pacific, an end-of-life doula, explored the toll climate change takes on environmental science professionals.

Dr. David Sischo’s favorite tree snail species, Achatinella fulgens, in the Department of Land and Natural Resources’ Snail Extinction Prevention Lab. It is currently extinct in the wild. (Leilani Combs/Civil Beat/2025)

Dr. David Sischo’s favorite tree snail species, Achatinella fulgens, in the Department of Land and Natural Resources’ Snail Extinction Prevention Lab. It is currently extinct in the wild. (Leilani Combs/Civil Beat/2025)

Individuals in conservation careers work at the forefront of the climate crisis, often responding to things most people assume are far in the future. Environmental scientists can’t take a break from the existential threat of climate change because it has become the very focus of their work.

“My team is on the frontline of extinction,” said David Sischo, a wildlife biologist with the Department of Land and Natural Resources and one of the session’s panelists. “We deal with it every day.”

Like Tears In The Rain

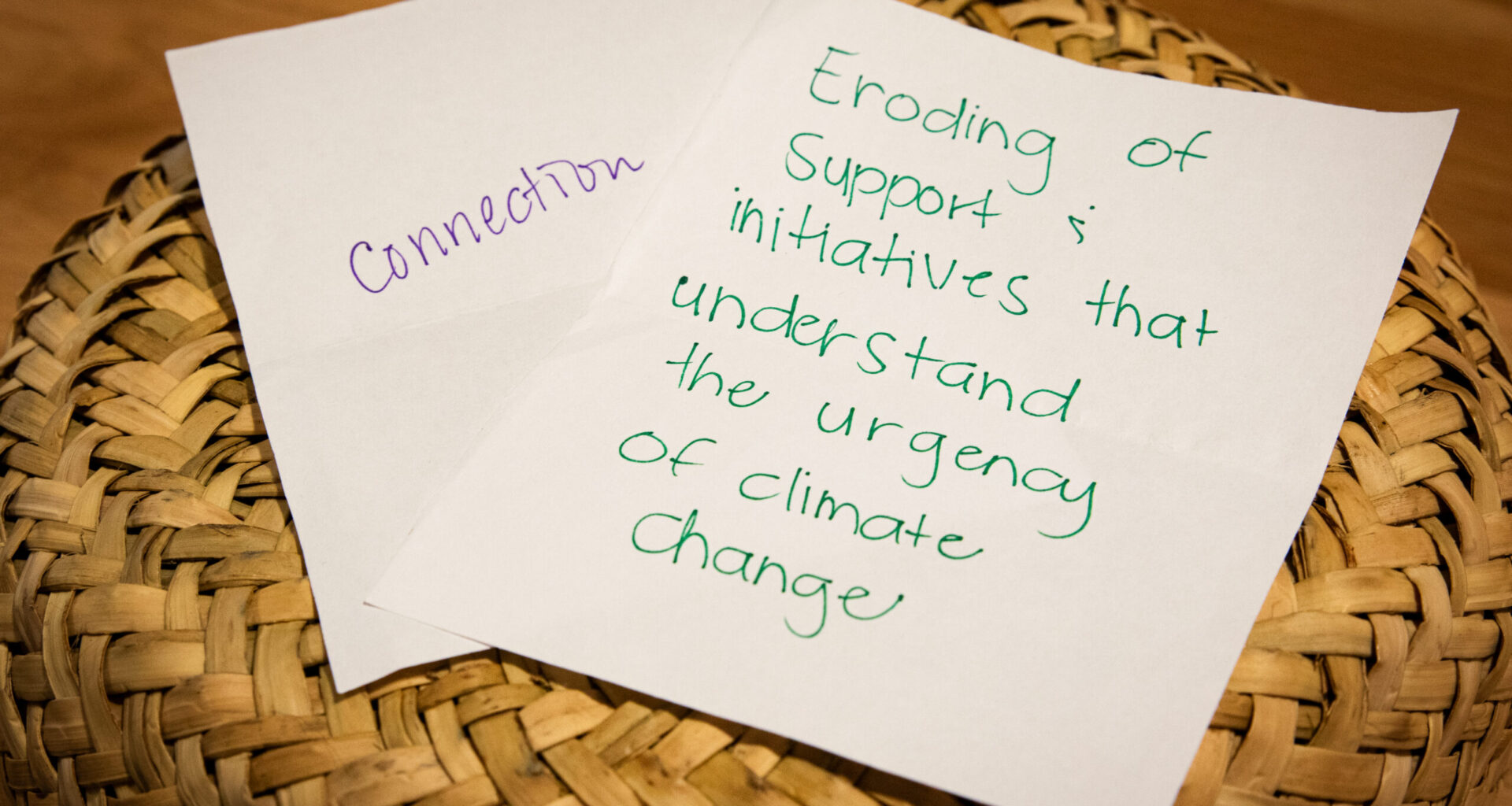

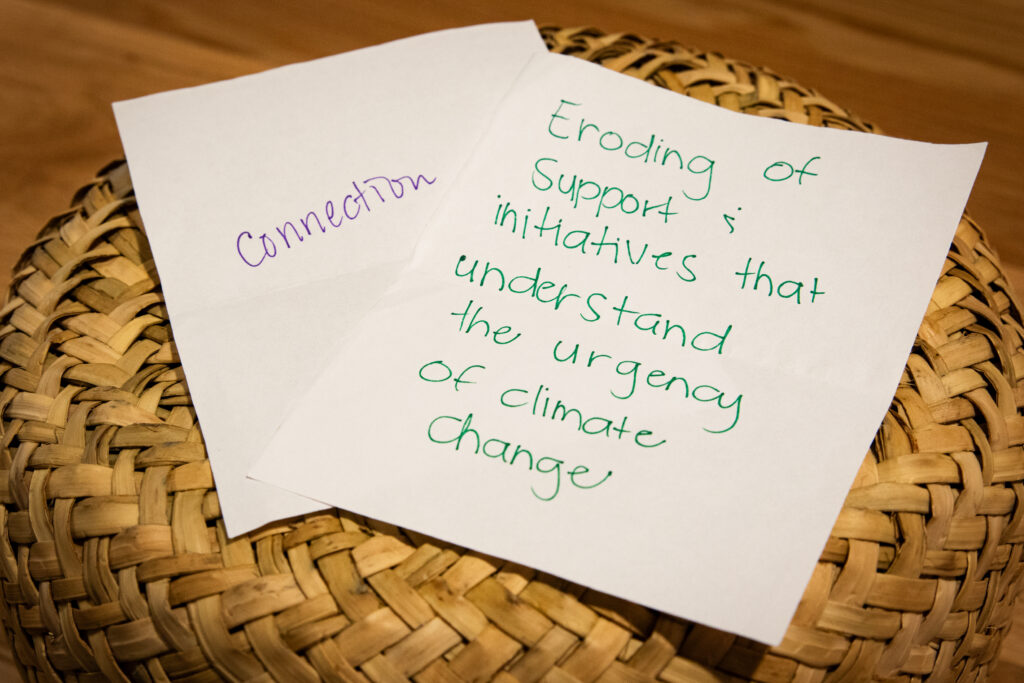

The woman behind the table in Room 312 instructed each person who entered to take one of the pieces of scrap paper and a colored pencil and then write something about grief related to ʻāina — the Hawaiian word for land and people’s connection to it — or conservation. In the center of the table sat a wooden bowl to collect those scrap paper entries.

The room filled slowly as a crowd clad in aloha shirts and lei made small talk, reusable water bottles in hand. Members of the organizing team offered grass mats to those spry enough to sit on the floor to keep the chairs open for those who needed them. In the end, those mats were needed: Around 120 people made their way into the session that day — standing room only.

Then, it began. The bowl made its way around the room as each audience accepted the offering, selecting a piece of one another’s grief. In the order they were chosen, voices began to reveal their messages.

“Permanence, employment, funding and connection,” one person called out.

“Feeling like no matter how much progress we make, we’re always losing ground,” another reader declared.

“I grieve for earth’s species that are slipping through our fingers like water,” yet another went on.

The voices continued in quick succession until every note had been read. A hush fell over the room. Some in the crowd wiped away tears, and tissue boxes were passed. For a conference rooted in scientific rigor, it was an unusually raw and emotional moment that got to the heart of why everyone was there in the first place.

Short messages about ʻāina and conservation-related grief shared at the Hawaiʻi Conservation Conference session called Dialogue on Navigating Grief to Support Capacity in Conservation: Processing the Loss of Species and Climate Change (Leilani Combs/Civil Beat/2025)

Short messages about ʻāina and conservation-related grief shared at the Hawaiʻi Conservation Conference session called Dialogue on Navigating Grief to Support Capacity in Conservation: Processing the Loss of Species and Climate Change (Leilani Combs/Civil Beat/2025)

Reflecting back on that moment, Pacific said that exercise has garnered the most response from those she has spoken to since. Having everyone read each other’s messages had been a last-minute decision, one that made all the difference for how the session moved forward.

“That allowed, first of all, people’s actual voices to be heard, their leo, but also their internal voice,” said Pacific, who helped design the seminar based on how she would run small group grief sessions in her death doula practice, “Their internal grief voice was then put into the room, and we all held that together.”

Pacific found her capacity to engage with grief through her own experience with the loss of her father. Now as a doula, she sits with those close to the end of their lives to, in a sense, witness their grief and help navigate the emotional and practical logistics of preparing for death and bereavement.

After crashing an afterparty for the previous year’s conservation conference at the invitation of a friend, Pacific recognized the need for grief support within the environmental science and conservation industries. She said that as people at the party found out what she did for a living, the conversation would turn. It seemed to her that these people had a lot to process.

“I wondered who was helping you through this grief, like an HR department, and found out there wasn’t anyone,” Pacific told the audience at the conference this year.

A new “talk story” session format added to the conference this year made possible the non-traditional science presentation, entitled, “Dialogue on Navigating Grief to Support Capacity in Conservation: Processing the Loss of Species and Climate Change.” The panel consisted of six conservation professionals from organizations including the U.S. Forest Service, the Department of Land and Natural Resources, The Nature Conservancy and the American Bird Conservancy.

David Sischo sorts through snail species in the Snail Extinction Prevention Lab. Around 40 species within the lab are currently extinct in the wild. (Leilani Combs/Civil Beat/2025)

David Sischo sorts through snail species in the Snail Extinction Prevention Lab. Around 40 species within the lab are currently extinct in the wild. (Leilani Combs/Civil Beat/2025)

After the seminar, Sischo, who coordinates the state snail extinction prevention program, said he appreciated getting to hear from everyone in the room.

“It was painful hearing all that, but it was also really comforting, in a way, to know that everyone is… feeling the same feels and going through the same thing,” he said, “That was nice to see, because I think in my professional life and personal life, I don’t always feel that.”

The snail extinction prevention lab is home to 40 species of snails unique to Hawaiʻi that Sischo said are now considered to be extinct in the wild.

“If you walk into our laboratory and you know what is in there… you’re like, ‘Holy shit, like these are the last animals of their species, and they’re all in one room,’” he said. “So it’s heavy.”

During the session, Sischo told the room about his team’s search for a species of snail on the Punaluʻu summit of the Koʻolau Mountains on Oʻahu. The Achatinella lila is a small mollusc with a beautiful spiral shell, whose colors can vary from a gradient of green and orange to a dark umber. Lighter colors run along the creases that separate sections of the spiral.

Containers of endangered snails in the Snail Extinction Prevention Lab in Pearl City on Oʻahu. (Leilani Combs/Civil Beat/2025)

Containers of endangered snails in the Snail Extinction Prevention Lab in Pearl City on Oʻahu. (Leilani Combs/Civil Beat/2025)

These tree snails were abundant in the mid-2010s, but the lab decided to establish a backup colony in captivity to be safe. When they returned to collect samples, they could only find one individual.

The discovery set off an extensive 200-man-hour snail hunt that turned up three more.

“I didn’t realize I was one of the unlucky ones,” Sischo said, tearing up, “The last to see them.”

His neighbor on the panel, Sam ‘Ohu Gon — a senior scientist and Hawaiian cultural advisor with The Nature Conservancy — put his hand on Sischo’s shoulder. Gon has seen four species of Hawaiian birds go extinct during his over 40-year career.

During his fieldwork, Gon told the room that he had had a similar experience with the last of the Maui ō’ō, a type of Hawaiian Honeyeater and the Maui nukupu’u, a species of endemic Hawaiian Honeycreeper.

“At the time that you make those sightings, you don’t believe that you’re the last person to see them,” he said, “You firmly believe that you will see them again.”

Life Finds A Way

Hawaiʻi has been particularly impacted by extinction events. Of the 142 bird species native to the Hawaiian islands alone, 95 are now extinct and 11 are missing, according to the American Bird Conservancy.

“We are one of the Endangered Species capitals of the world,” said Elizabeth Speith, a specialist with the Hawaii Invasive Species Council who was unable to make it for the panel that day. “We also have the dubious title of being one of the invasive species capitals in the world.”

Like many in conservation fields, Speith not only works in the industry, but spends her spare time volunteering with conservation groups as well. She also volunteers with the nonprofit partner of Haleakalā National Park, Friends of Haleakalā.

“We aren’t doing it for the money; we are completely doing this because of our passion,” Speith said. “But we also are doing this within the context of the dispassion of science, which is all about objectivity and removing bias. And so there can often be, like, a kind of conflict in that.”

The professional and often government environment of science can leave little space for conversations about the emotional toll of the work. According to Sischo, whose team works directly in extinction, they do acknowledge the gravity of the situation during their field work “but for the most part, we probably don’t unpack it enough and I recognize that.”

A victim of rapid ʻōhiʻa death stands bare in Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park on the Big Island. A genetic test verified the tree’s demise. (Kevin Fujii/Civil Beat/2024)

A victim of rapid ʻōhiʻa death stands bare in Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park on the Big Island. A genetic test verified the tree’s demise. (Kevin Fujii/Civil Beat/2024)

In Hawaiʻi, the unique crossover between science and traditional Hawaiian practices within the realm of conservation offers a more open framework to navigate grief. Some believe that the ʻāina, the plants and animals are just as much their relatives as their human family members, which helps break down some of the disconnection humans may experience with the natural world.

“The whole idea of treating the living world around you as full of conscious relatives and beings that you treat like you would treat a beloved person,” Gon said, “I think that’s a part of the whole idea of, at least, how Hawaiians would deal with grief.”

However, this kuleana, or responsibility, to the land can be an added burden for Hawaiians working within the conservation field. Kylle Roy, one of the panelists. Roy, an entomologist with the U.S. Forest Service, later said that at first she sometimes struggled with being the “token Hawaiian” on her teams.

“Being a Native Hawaiian in conservation experiencing grief, you kind of get an extra level of responsibility because this is your land and your culture,” she said.

Over her time working with rapid ʻōhiʻa death, a disease caused by fungus that has led to graveyards of the trees throughout the islands, she began to connect with her kuleana differently. As she got older, she said her connection to the ʻāina gave her an opportunity to step into a role as a leader.

“It was no mistake that there were so many Hawaiian practitioners on the panel,” Gon said. “Hawaiian practitioners have no trouble getting emotional about things and therefore feel comfortable about expressing that … even in the work that they do.”

At the Hawaiʻi Convention Center in room 312 that day, the popularity of the session underscored the need for a way to process that shared grief. It also seemed to revitalize people about the shared experience itself.

Gon said that he felt confident people left that room with a new sense of responsibility.

“You notice by the end of that grief session, how many people left with a stronger sense of commitment to continue work that they do,” Gon said. “Because shared grief is one of those things, you know, it’s almost like (the extinct species) will not have died in vain.”

After the room emptied, Pacific collected all of the little white pieces of paper filled with expressions of grief, took them home and burned them using small branches from an ʻōhiʻa tree— symbolically releasing them back to where they came from.

Civil Beat’s coverage of climate change and the environment is supported by The Healy Foundation, the Marisla Fund of the Hawai‘i Community Foundation and the Frost Family Foundation.

Sign up for our FREE morning newsletter and face each day more informed.

Sign Up

Sorry. That’s an invalid e-mail.

Thanks! We’ll send you a confirmation e-mail shortly.