The origins of Mural Arts Philadelphia

Mural Arts Philadelphia was born inside the Philadelphia Anti-Graffiti Network, a project started in 1984 by Tim Spencer during Mayor Wilson Goode’s administration to curb vandalism, mostly through various forms of punishment and control of graffiti writers.

Golden, as a part-time employee, suggested a carrot to go along with that stick: What if she rallied graffiti artists to channel their talents toward legal murals instead of illegal tags? In 1986, the anti-Graffiti Network launched that idea as the Mural Arts Program.

At the time, the network required participating graffiti writers to sign an official statement agreeing to no longer deface property, which Golden knew was never going to stick.

“Nobody was like, ‘I’m changing right away,’” she said. “Then they wrote my name. They wrote ‘Cool Jane.’ I’ve never been cool. I would just say, ‘You have to stop. You have to stop writing my name.’ Tim Spencer would go, ‘Who’s Jane?’ and they would say, ‘Oh, some girl from Kensington.’”

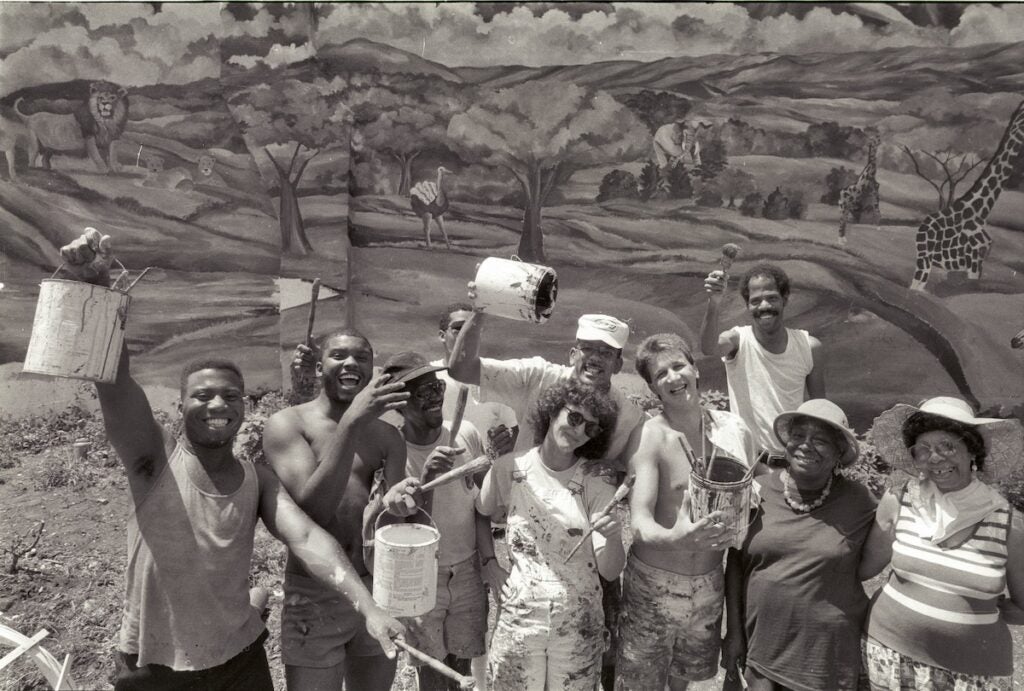

Jane Golden and the Anti Graffiti Network crew in 1985. (Courtesy of Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, as part of the Philadelphia Inquirer Collection)

Jane Golden and the Anti Graffiti Network crew in 1985. (Courtesy of Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, as part of the Philadelphia Inquirer Collection)

To the best of her knowledge, there are no ‘Cool Jane’ tags existing anymore.

“Once I was on Amtrak and I saw one,” Golden said. “It was funny.”

One of the caveats of the Mural Arts Program was a ban on spray paint. Golden said the Anti-Graffiti Network would allow its artists to paint on approved walls with brushes only. Spray paint was too closely associated with graffiti.

Over the years, Golden relaxed that rule.

“Spray is a tool like anything else,” she said. “I find good graffiti art fascinating. It’s beautiful. Some people have been critical, they’re like, ‘You can’t condone this.’ Well, I am hugely supportive of it, but it has to be done legally. That’s the litmus test for me.”

Those early years were not easy. Golden had bad equipment and supplies, which often got stolen. Wary residents often didn’t know what a mural was or why there should be one in their neighborhood. The work was done in all kinds of weather under impossible conditions.

“It’s not like there was a blueprint or a road map. We didn’t have a strategic plan. Nothing,” Golden said. “We had our will. We had passion. We had excitement.”

Golden’s’ first test came immediately. In 1984, Rev. Jesse Jackson chose Philadelphia as the first stop of his presidential campaign. Mayor Goode looked at the Spring Garden Bridge, the gateway to the mostly Black neighborhoods of West Philadelphia, and saw a mess: it was covered with graffiti.

Jane Golden paints ”Life in the City,” on the Spring Garden Street Bridge, one of the first murals painted by the Philadelphia Anti-Graffiti Network in 1984. Young people from the Mantua neighborhood assisted in the painting of the mural, many of whom were graffiti writers at the time. (Courtesy of Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, as part of the Philadelphia Inquirer Collection)

Jane Golden paints ”Life in the City,” on the Spring Garden Street Bridge, one of the first murals painted by the Philadelphia Anti-Graffiti Network in 1984. Young people from the Mantua neighborhood assisted in the painting of the mural, many of whom were graffiti writers at the time. (Courtesy of Temple University Libraries, Urban Archives, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, as part of the Philadelphia Inquirer Collection)

The mayor wanted the entire 700-foot bridge repainted with a mural, and quickly.

“They said ‘If you can do this mural in three weeks, you could have a full-time job,’” Golden recalled. “I wanted that full-time job.”

“I had all the kids from Mantua, a crew of like 100 kids, mostly graffiti writers. It was so disorganized. We had a sketch and they kept deviating from the sketch,” she said. “Then we had this big dedication with all the news teams there. Wilson Goode looked to me and goes, ‘Well, I guess I owe you something.’ That full-time job. I went from $12,500 to $20,000. I was so excited.’”

Finding a successor

In 1996, the Anti-Graffiti Network was absorbed into the city’s Parks and Recreation Department, becoming the Graffiti Abatement Program and the Paint Voucher Program to prevent and clean up graffiti. Mural Arts was spun off as an independent organization supported by public and private funds.

In 2016, it changed its name to Mural Arts Philadelphia. It now has a $16 million annual budget, less than a quarter of which comes from the city.

“Art changes lives,” Mayor Cherelle Parker said. “As we honor Jane’s remarkable impact on Philadelphia’s social and physical landscape, we look ahead with excitement to the future of Mural Arts.”

Parker moved Mural Arts from Parks and Recreation into the office of arts and culture, now called Creative PHL.

“I’m both saddened and excited for Jane,” said Val Gay, Philadelphia’s chief cultural officer who oversees Mural Arts in City Hall. “But I’m saddened for all of us, in that she is a legend.”

Philadelphia’s Chief Cultural Officer Val Gay poses in front of the mural that wraps around the Markward Recreation Center. The program that created the mural is intended to help young people at risk of becoming the victims or perpetrators of violence. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Philadelphia’s Chief Cultural Officer Val Gay poses in front of the mural that wraps around the Markward Recreation Center. The program that created the mural is intended to help young people at risk of becoming the victims or perpetrators of violence. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

The growth of Mural Arts over four decades can be attributed, in part, to Golden’s raw energy. She has been known to intimidate elected officials who follow her at dedication events because they cannot match the same degree of energy at the podium.

Gay believes Mural Arts is stable enough to carry on without its founder’s infectious energy.

“I think we have the benefit of two things: One, we have the benefit of a personality, but we also have a strong organization,” she said. “Sometimes they don’t always go together. Mural Arts is a vibrant and well-run organization with a great staff.”

But Lovell is not so certain. In her office at the Visitors’ Center, she said tourism is driven, in part, by Philadelphia’s public art, of which murals play a huge role. She cannot see a way forward for Mural Arts without Golden.

“I don’t know what Mural Arts is without Jane. It is Jane and Jane is it,” she said. “It makes me anxious because I love the organization. I love the program. It makes me very nervous about what the future holds.”

The search for a new executive director has not yet begun. Board Chair Hope Comisky said a search committee has formed with the understanding that finding someone with the same characteristics as Golden is unrealistic.

“We can’t do that. We’re not putting any parameters around who that person will be,” she said. “That’s why it really is important – and we’re delighted – that Jane has agreed to continue at least for another three months after the official ending of her term to help us navigate through all of the issues we may encounter.”