New York — I knew I was in the right place because of the backpacks.

Six years ago, I needed something that could carry my laptop, my camera, a couple of lenses, and my audio equipment, but also be used as a normal backpack on days I was traveling a little lighter. I settled on the Peak Design Everyday Backpack. It’s a great backpack, and I use it all the time. What I didn’t know when I bought it was that it would soon become ubiquitous as the go-to backpack of journalists and tech-types alike.

All this to say: When I saw the person walking into the Chelsea event space in front of me had the same backpack as me, I knew he was either a journalist or an engineer.

I was there for the first-ever Protocols for Publishers showcase, the opening event of a two-day session that brought together people from the journalism and tech worlds to talk about the future of the internet. It was sponsored and hosted by three tech initiatives — Unternet, Graze, and Free Our Feeds — and motivated by a central question: how do we build an internet that works for publishers, rather than making them work for the internet (and the tech companies that control it)?

The short answer is that nobody really knows. But there is a lot of excitement around the potential of the federated internet, and particularly the AT Protocol, which — to summarize greatly, in the hope of sparing us a long technical tangent — is the architecture underlying Bluesky and associated apps, like the Instagram alternative Flashes.

The short answer is that nobody really knows. But there is a lot of excitement around the potential of the federated internet, and particularly the AT Protocol, which — to summarize greatly, in the hope of sparing us a long technical tangent — is the architecture underlying Bluesky and associated apps, like the Instagram alternative Flashes.

“We are in a moment of epistemic fracture,” said Ivan Sigal, interim director of Free Our Feeds. The information ecosystem has fractured, he said, and it’s becoming increasingly fractured as the internet becomes flooded by and oriented around AI. “Silicon Valley seems to be leaving the space of consumer-focused social media,” he continued, which means that “we need to build out systems that will serve us in the long term.”

It was refreshing to hear from people working in tech who were eager to help publishers face the problem head-on. Too often lately it has felt as though tech companies are more interested in forcing publishers to play by their rules.

In some ways the showcase and the invite-only summit the day after — which included people like ProPublica director of technology Ben Werdmuller, Semafor executive editor Gina Chua, and product team members from The New York Times and Washington Post — felt like attending a planning meeting for an underground zine, albeit a little less punk rock. If the internet of yore, increasingly enshittified by big tech, is the mainstream, perhaps the AT Protocol is the counterculture.

The power of the AT Protocol is in its flexibility, and in the fact that it can’t be tightly controlled the way that, say, Elon Musk can assert his will on X/Twitter. This is the real promise of the federated web: If your preferred way of accessing your preferred protocol suddenly becomes worse, you can pick up stakes and move to another app that accesses the protocol in a way you like better without having to create a new login or rebuild follower/following lists.

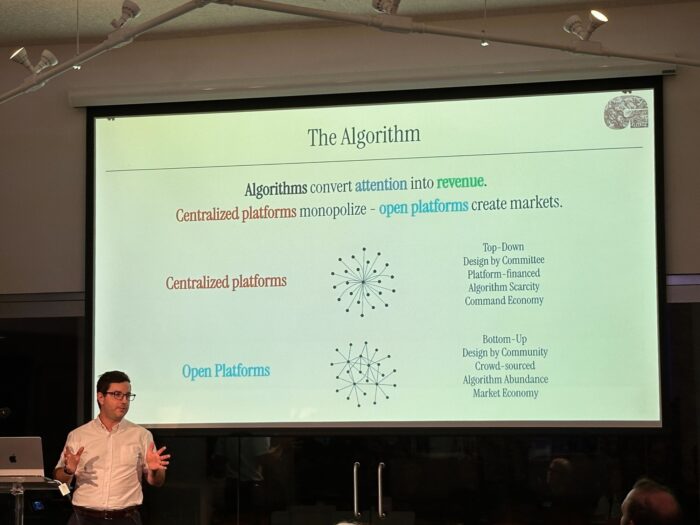

“Everyone is forced to exploit people less, systemically,” said Devin Gaffney of Graze, which helps publishers build custom feeds for Bluesky (earlier this year, Graze helped the NBA build a custom feed for the playoffs). Large publishers, he said, are the “charismatic megafauna” of the internet. To extend the metaphor further, that means that if they start paying attention to things like the federated web sooner, they will have more of an opportunity to shape how the ecosystem works rather than being forced to adapt to whatever shape it settles into.

The AT Protocol, and the federated internet broadly, feels like it’s in opposition to AI in many ways. At one point, Ted Han of Mozilla commented that “it’s interesting how so many of the conversations we’re having are about competition with AI.” Both offer different ideas of the individualized internet: AI is a siloed but deeply personal experience, with every person’s experience being determined by their conversations with a chatbot, while the federated internet is more oriented around active participation in chosen communities (as, to be fair, are current-day discussion boards and subreddits).

There was a lot of emphasis on feeds at the summit, and we’ve already seen some publishers lean into this idea. Both the Verge and SB Nation redesigned their sites to reorient around the idea of custom feeds, albeit served up through their home pages.

The real question publishers have to grapple with, said Semafor’s Chua, “is if we’re interested in saving the ecosystem or saving ourselves.” Individual organizations can survive in a destroyed ecosystem, she pointed out, and the most cynically business-minded among us may even argue that doing so is good for business. But for publishers to thrive, they need to figure out how to both address the rise of AI, which feels inevitable, and connect directly with audiences who are hungry for information.

By the time the summit ended, the path forward still seemed unclear. But, the organizers said, it was just the beginning of the conversion; there will likely be more Protocols for Publishers meetings — and similar ones, like Protocols for Artists — in the future.

“It’s like a meeting of the people who make building codes,” said Boris Mann, one of the organizers. “It might sound boring and technical, but it’s the kind of thing we need to do so we can be sure the buildings stay standing up.”

Photo of Devin Gaffney of Graze at Protocols for Publishers by Neel Dhanesha.