Some summer days while I was in high school, my dad would give me a $20 bill, and I would take the train into the city for a drop-in life drawing class at the Art Students League of New York in Midtown. I wasn’t a very good student. Half the time, I’d pocket the money instead, and wander around the park or meet my friends downtown. But on at least a few occasions, I did head into that French Renaissance-style building, up those marble steps, and into one of many classrooms, where for a few hours, the only sound would be the scritch scritch of many hands hatching into paper.

As such, I suppose you could count me among the hundreds of thousands of alumni of the Art Students League, which is celebrating its 150th anniversary this year. Founded in 1875 by a group that splintered off from the more conservative National Academy of Design, it was intended to give students access to materials, classes, and studios regardless of financial, technical, or scholarly backgrounds. It has never granted degrees — nor even grades. It’s been associated with a seriously prestigious list of artists: Thomas Eakins and Augustus Saint-Gaudens were early board members; Thomas Hart Benton, William Merritt Chase, Stuart Davis, and George Grosz were among the many instructors; Norman Rockwell, Jackson Pollock, Helen Frankenthaler, Donald Judd, Jacob Lawrence, and countless other household names were students. And still more quietly filtered back into the city or elsewhere, bringing a kernel of the League with them that ripples invisibly through the annals of American culture.

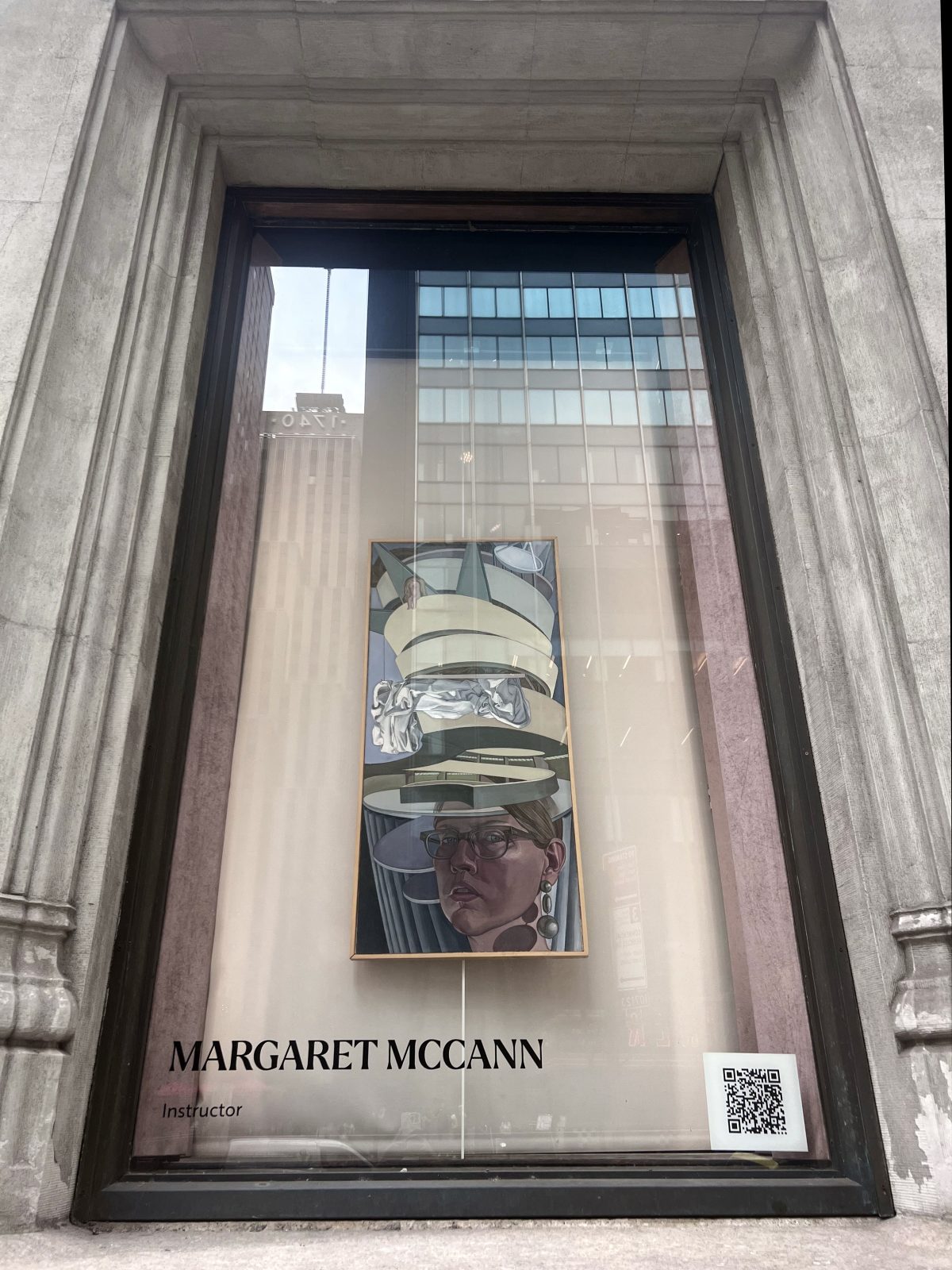

Installation view of works by Margaret McCann and Sharan Sprung from the sidewalk outside the Arts Students League building

Shaping American Art: A Celebration of the Art Students League of New York at 150, held at the namesake institution, explores its impact on American art. Certain parts of the exhibition’s stated scope — examining “how artists have changed and been changed by their time at the League,” for instance — feel underbaked. Still, the League’s influence is clearly felt, and the exhibition is both celebratory and awe-inspiring. It leans heavily on the name recognition of its artist list and the aura of its environs, but that’s more than enough.

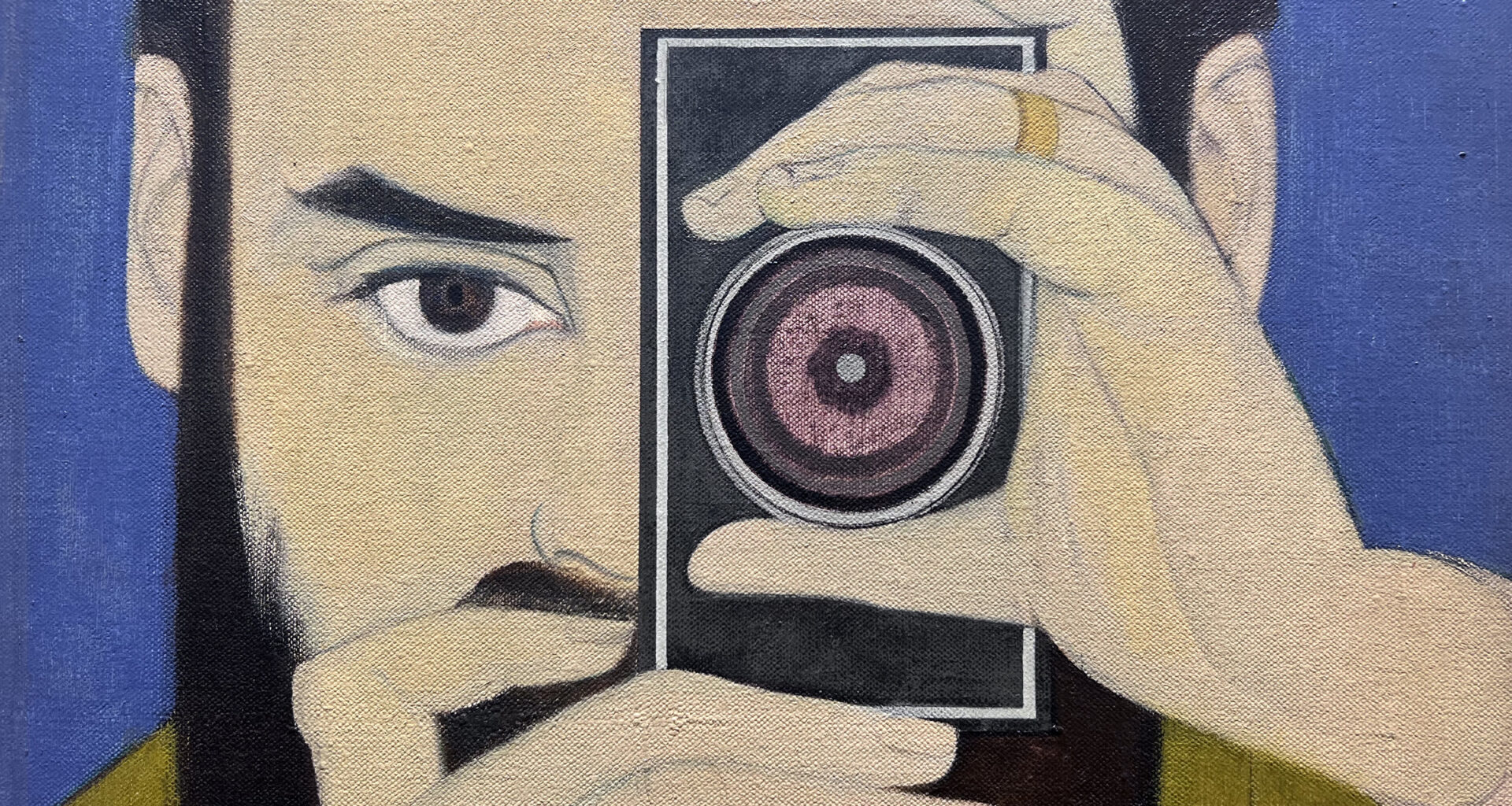

It begins in the windows facing the sidewalk, where works by League instructors Margaret McCann, Daisuke Kiyomiya, and Sharon Sprung meet the reflection of the buildings across the street, integrating its ongoing history with the city itself. The entrance hall puts you in the company of luminaries, with drawings by Norman Rockwell and Winslow Homer, and paintings by Georgia O’Keeffe and William Merritt Chase, among many others. These works could take pride of place in most museums, but here, they share space with such quotidian company as an elevator, an art supply store, and a fire alarm control panel, a testament to the casual abundance of the League’s collection. Enter the Registration Office and you might encounter drawings by Robert Henri, paintings by Max Weber, and sculptures by Alexander Stirling Calder, alongside a student asking about course credits.

Installation view of Shaping American Art: A Celebration of the Art Students League of New York at 150 featuring works by John Fabian Carlson and Preston Dickinson

Shaping American Art can as a result sometimes have the haphazard feel of a student show — which, if you think about it, it is. The Henri, for instance, seems like it might be a study, even a doodle: A figure on the left with the proportions of a caricature seems to paint at an easel — a quick, lighthearted vignette of a fellow student? O’Keeffe painted “Dead Rabbit and Copper Pot” (1908) when she was around 20 years old, and though her talent is undeniable, the work itself is a bit uneven: The titular objects are set almost entirely in the top half of the composition, leaving the foreground oddly blank. Upstairs, there’s a drawing by Donald Judd of what might be the view from his studio window, utterly incompatible with the sculptures and movement for which he would become known.

It’s moving to encounter such works because it returns names that have been calcified in their greatness to what they once were — students who probably dreamt about becoming what they became in this very building. Experiencing these works here is the very opposite of that intended by a white cube, which seeks to suppress all but the visual elements of the work on view. If an artwork has an aura — some indefinable essence of the artist that a viewer can feel — then this building is positively alive with that energy.

Georgia O’Keeffe, “Dead Rabbit and Copper Pot” (1908), oil on canvas

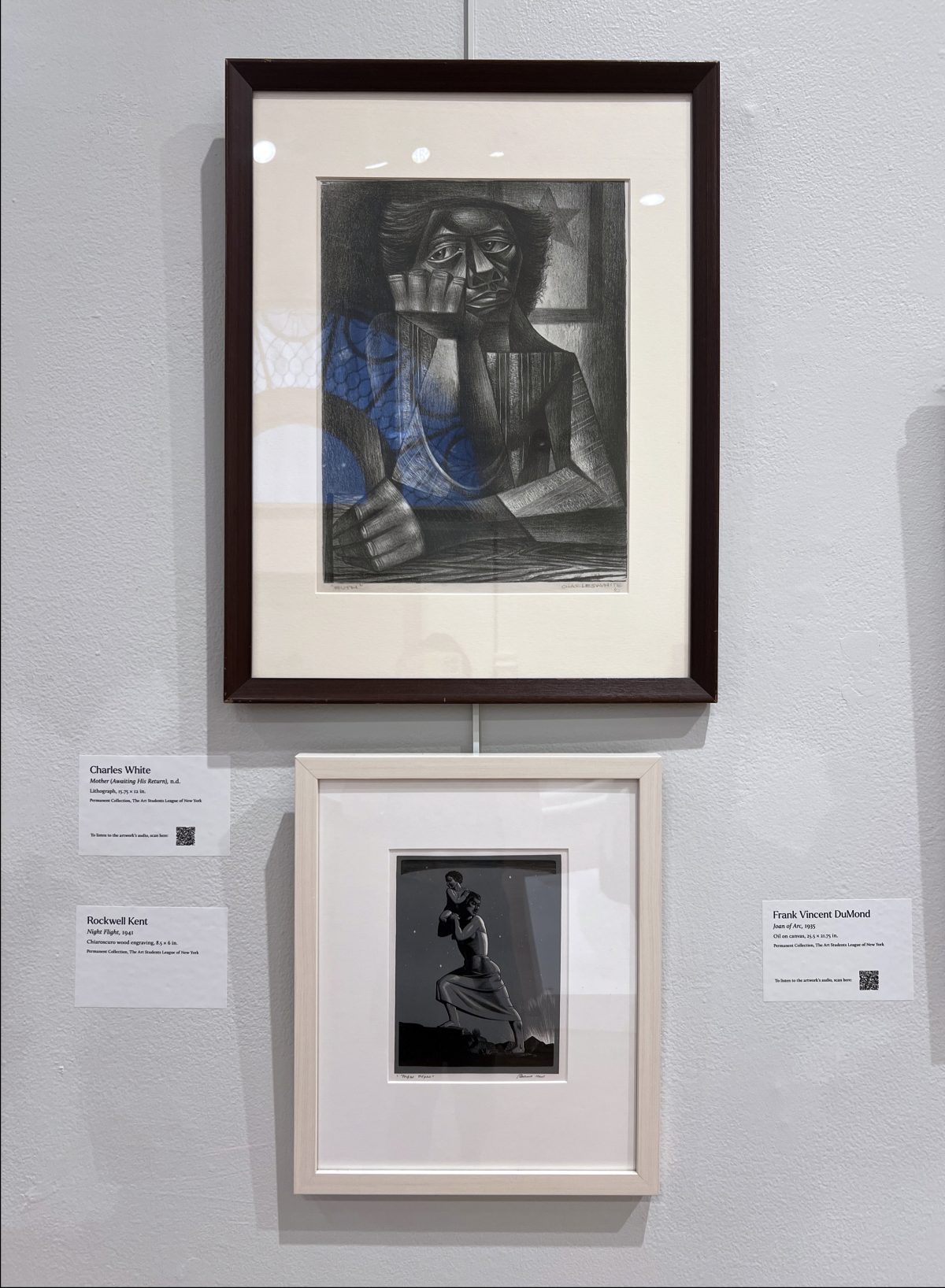

I was alternatively charmed and disappointed by the curation. The exhibition is divided into basic sections like “Exploring Landscapes” and “Before, During, and After War” (which, if we’re being technical, applies to all of time). That leads to some fun pairings — where else might you see a Carmen Winant next to a Milton Avery? And it collides works from disparate movements under these banners — a cubist work by Charles White beside Frank Vincent DuMond’s Waterhouse-like “Joan of Arc” (1935) — shaking up typically siloed categories. The language in these texts are accessible to a general audience, which is generally a positive, as in “In this section, these works tell the story of how … land has been modified, adapted, and enjoyed.” But sometimes it’s not enough: “This section presents artworks that defy categorization,” for example, or “The works in this section tell these stories better than a wall text could.”

How have artists changed and been changed by their time at the League? I craved specificity in that answer — smaller strands, individual stories that could be woven into that larger narrative of its undisputed influence on American art. This is hinted at: One section label mentions that sculptor Tony Smith credits his volumetric thinking to the teachings of Vaclav “Vit” Vytlacil (also on view across the room), and the Bloomberg Connects app offers more information on certain works that a dogged visitor could put together into something like the above. Still, the mantle might more appropriately be taken up by a museum or institution. Besides, there’s ample opportunity for this exhibition in the future — in this very building, the next crop of artistic luminaries work diligently behind closed doors.

Installation view of Shaping American Art: A Celebration of the Art Students League of New York at 150 featuring works by Seong Moy, Joyce Pensato, Vaclav Vytlacil, and Peter Max

Robert Henri, “Untitled” (undated), crayon on wove paper

Winslow Homer, “Sea and Rocks During a Storm” (1896), lithograph

Installation view of Shaping American Art: A Celebration of the Art Students League of New York at 150 and the store

Donald Judd, “Untitled” (1951–52), lithograph in black on Basingwerk parchment paper

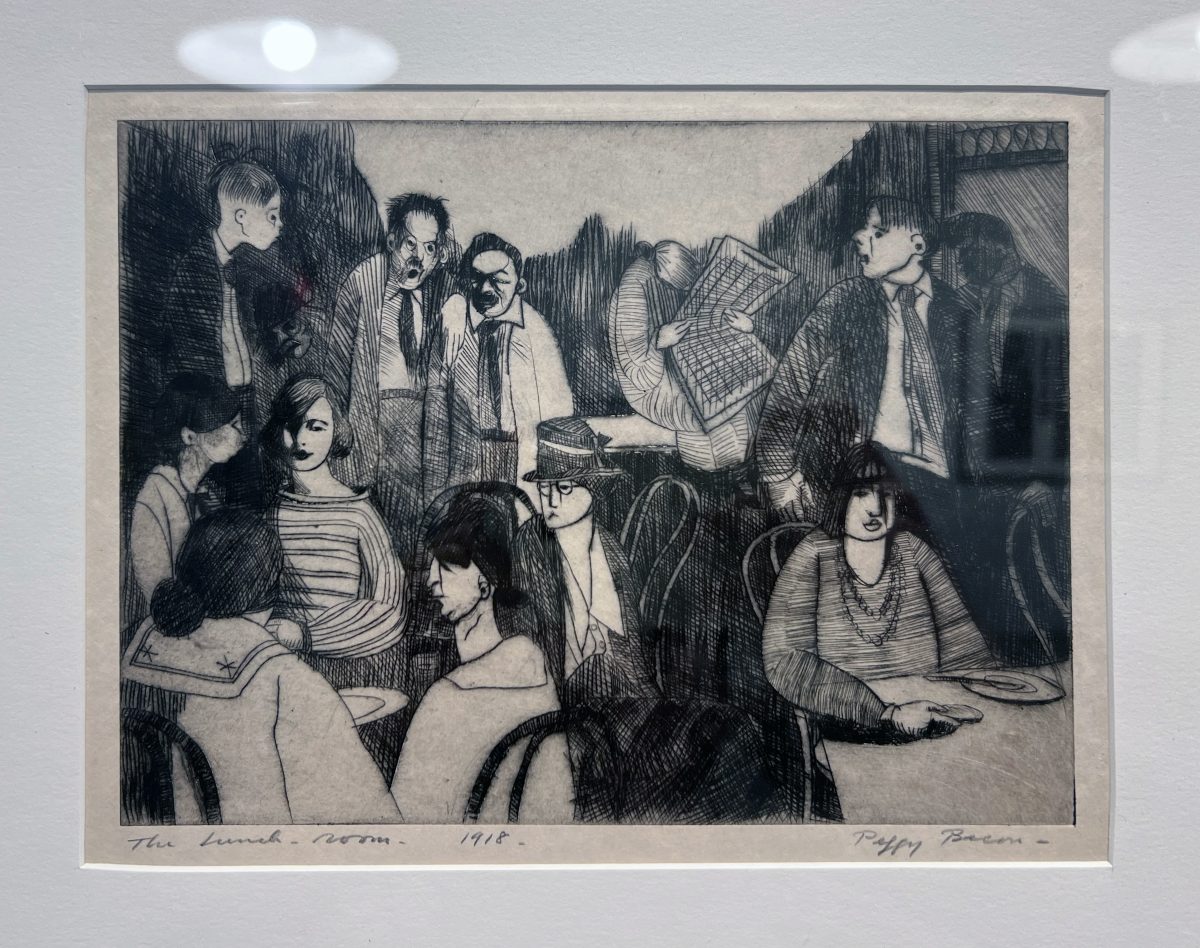

Peggy Bacon, “Lunch at the League (The Lunch-Room)” (1918), drypoint etching

Installation view of Shaping American Art: A Celebration of the Art Students League of New York at 150 in the cafeteria

Left: Installation view of Shaping American Art: A Celebration of the Art Students League of New York at 150 featuring works by Carmen Winant, Milton Avery, and Stewart Klonis; right: Tony Smith, “Spitball” (1970), granite

Installation view of Shaping American Art: A Celebration of the Art Students League of New York at 150 featuring works by Robert Rauschenberg (foreground), Charles H. Alston, Knox Martin, Al Held, Iria Leino

Left: Frank Vincent DuMond, “Joan of Arc” (1935), oil on canvas; right: Installation view of Shaping American Art: A Celebration of the Art Students League of New York at 150 featuring works by Charles White and Rockwell Kent

Shaping American Art: A Celebration of the Art Students League of New York at 150 continues at the Art Students League of New York (215 West 57th Street Suite 1, Midtown, Manhattan) through August 16. The exhibition was curated by Esther V. Moerdler and Ksenia Nouril.