AMBLER, Pa. — They are boldface names with swagger to spare. An October titan with his own candy bar. A high-kicking lefty with his first name on his back. A mustachioed closer who pointed at his victims. Depression-era champions. Steroid-era sluggers. A base-stealing savant who called himself the greatest of all time.

Reggie, Vida, Eck. Grove and Foxx. Canseco, Giambi, Tejada. Rickey. All of them played for the Athletics and won the American League Most Valuable Player award. All of them, and one more.

You will find him in his living-room easy chair in the Philadelphia suburbs, right where he’s lived for seven decades. Bobby Shantz turns 100 years old on Sept. 26. He is trim and tan with a shock of light blond hair, a bad hip, achy knees and a sense of wonder at the heights that a 5-foot-6 dreamer from Pottstown, Pa., could reach.

“Boy, I tell you, I really don’t know,” said Shantz, who was 24-7 with a 2.48 ERA for the Philadelphia A’s in 1952, when he beat out a trio of Yankees — Allie Reynolds, Mickey Mantle and Yogi Berra — for the MVP.

“When I was growing up, I never thought I ever had a chance to be a big-league baseball pitcher. I thought I might have a chance in the minor leagues, maybe, but I didn’t realize that I had enough stuff to be in the big leagues.

“But it turned out awful nice, I’ll tell you that — 16 years. You know, I lasted more than I thought I would. Boy, what a life. I really enjoyed every minute of it. Even when I was horseshit, I still liked it.”

Shantz is the second-oldest living MLB player, after Bill Greason, who turns 101 on Sept. 3 and pitched in 11 games for the Birmingham Black Barons and St. Louis Cardinals. Shantz lives with his wife, Shirley — they met in Nebraska in 1948, his only minor-league season — and a caregiver visits daily.

The Shantzes have four children, Robert Jr., Teddy, Danny and Kathy, and one of them is always at home to help their parents. Photos of the Shantzes’ three grandchildren and a great grandchild decorate the living room, and a friendly rescue dog, Jake, never strays far.

One morning in August, the mailman dropped off the usual assortment of autograph requests: a baseball, a photo, a dozen or more cards. A light day, Shantz Jr. said. His father signs everything, perhaps 200 items a week, with a penmanship that is still precise — and right-handed. Pitching was the only thing Shantz did as a lefty.

“Played golf right-handed, hit right-handed, wrote right-handed,” he said. “I didn’t do anything left-handed, I don’t think. I don’t know how in the hell I got to pitch left-handed, I really don’t. I’m glad I did.”

The 1952 season was by far Shantz’s best, by modern metrics (an MLB-best 8.8 bWAR) and those at the time. He led the AL in victories, strikeout-to-walk rate and twirled 27 complete games — including one that went 14 innings. He even struck out the side in the All-Star Game at his home park: Whitey Lockman, Jackie Robinson, Stan Musial.

Shantz did not win the Cy Young Award in 1952, for a very good reason — the honor had not been created. But his success landed him on “The Ed Sullivan Show,” (Shantz was nervous, but a $500 appearance fee took care of that) and his size made the story even better. In Shantz’s considerable lifetime, no other pitcher standing 5-feet-6 or shorter has thrown 200 innings in a season, as Shantz did three times.

Shantz’s stature had scared off most teams from signing him, but Shantz understood. When a Philadelphia Phillies scout, Jocko Collins, apologized for overlooking him, Shantz said that was OK; he had his doubts, too. After a while, though, Shantz’s talent made his size irrelevant.

“He made up for that because he could field probably better than most of the infielders,” said Bobby Richardson, 90, the New York Yankees’ second baseman when Shantz played in New York. “(Casey) Stengel played him in center field, if I’m not mistaken, in one game sometime. They didn’t even think about his size because he was so good.”

Overall, Shantz was 119-99 with a 3.38 ERA, and helped the Yankees win a championship in 1958. He also played for the Pittsburgh Pirates, Houston Colt .45s, St. Louis Cardinals, Chicago Cubs and Phillies, collecting eight Gold Gloves along the way.

“I’ll occasionally hear a guy introduce me and say, ‘He was the best fielding pitcher in baseball,’ and I’ll say, ‘No, Bobby Shantz was,’” said Jim Kaat, a Hall of Fame lefty with 16 Gold Gloves. “He didn’t win a Gold Glove until ’57. Had they given them out starting in ’50, he would have had 16 or 17 as well.”

Kaat, 86, grew up in Michigan, the son of a Philadelphia A’s fan. When the A’s played the Chicago White Sox, Kaat would pick up their radio broadcasts across Lake Michigan and listen to Bob Elson describe Shantz’s motion, how he landed on the balls of his feet and could dart in any direction for grounders.

Traded to the Yankees in 1957, Shantz impressed teammates with his athletic grace, the way he’d glide across the outfield for nifty catches in batting practice.

“He just loved to be active, a great competitor,” Richardson, who roomed with Shantz, said from his home in Sumter, S.C. “Bobby fit right in with the Yankees. Everybody loved him.

“It’s hard to believe, but back in those early days when I was playing with Bobby, there were no helmets in baseball and we were still traveling on the train. And we had some good times. The food on the train was tremendous — a dining car between two Pullmans. Not everybody liked it, but I just loved riding along after ball games, looking out at the farms.”

Richardson was religious, Shantz recalled with a laugh, and would gently remind him not to cuss so much on the mound. He hated to upset Richardson, whom he called his favorite teammate, but, well, Shantz couldn’t help himself.

“As a pitcher, you better start cussing,” he said. “Because sometimes you really need it.”

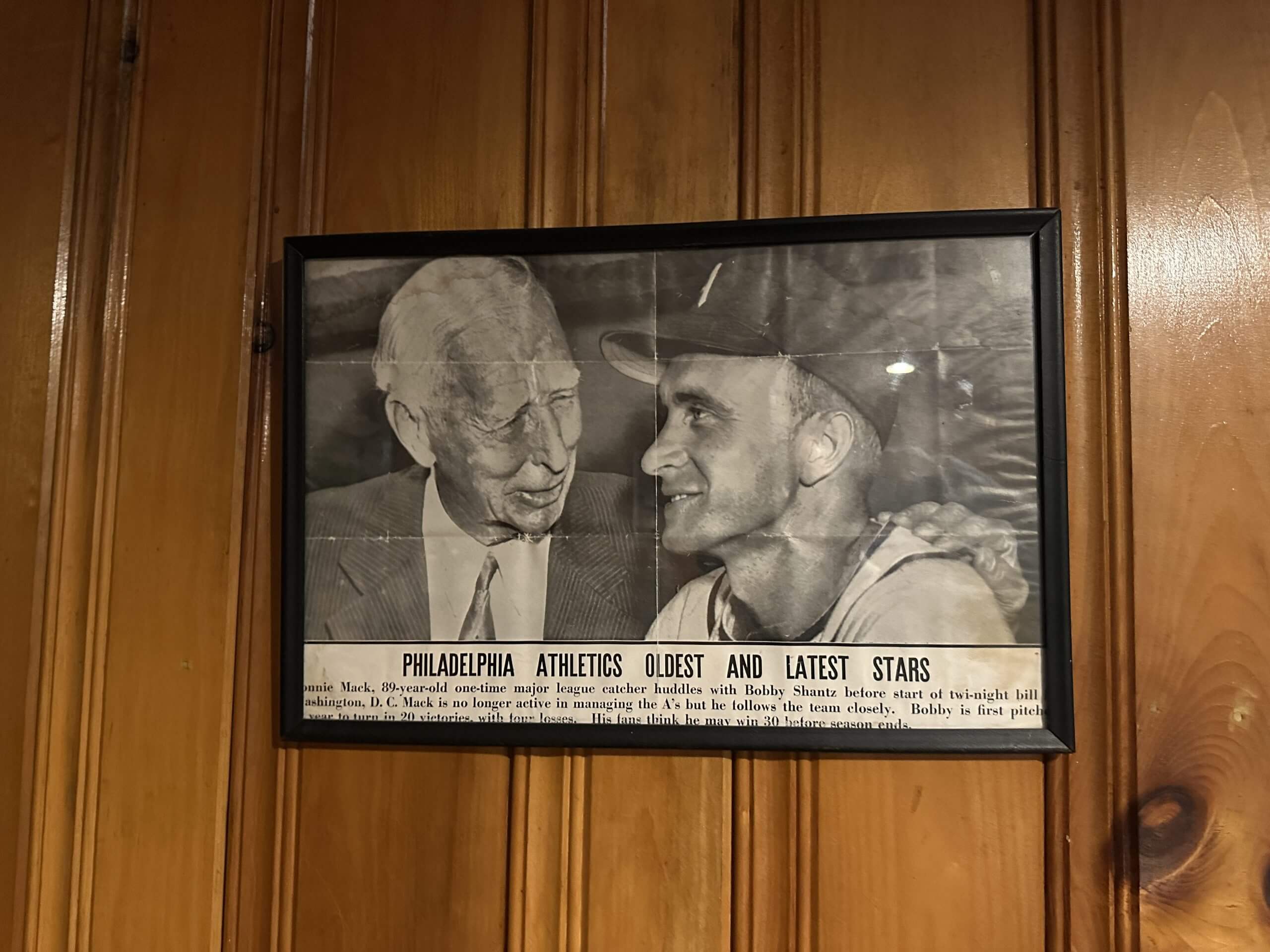

Shantz reached the majors in 1949 and played two years for Connie Mack, who was born during the Civil War, started his playing career in 1886 and managed the A’s for half a century. Mack didn’t like Shantz’s knuckleball, but other than that had little to say to the young lefty.

An enlarged newspaper photo of Mack and Shantz hangs on the wall in the basement of his Pennsylvania home. (Tyler Kepner/The Athletic)

“Connie Mack never talked to me — he never said a goddamn thing,” Shantz said. “He’s sitting on the bench and he wouldn’t say anything to me. I guess he would talk to a couple of coaches, but I’ve never really heard him talk that much. Nice man, though, real nice guy.

“Jimmy Dykes took over for Connie Mack and he never shut up. He was always talking. He was like Casey Stengel. He liked to talk.”

Dykes encouraged Shantz to use the knuckleball, which rounded out a repertoire built around a curve that Ted Williams once called the best in the American League. Only four pitchers struck out Williams more times than Shantz, who fanned him nine times in 66 plate appearances. Williams hit .344 for his career, but just .308 off Shantz.

“Oh, Ted, that son of a gun,” Shantz said. “Probably my toughest left-handed hitter that I had to get out. It was tough to fool him with that curveball. He knew he was going to get a curveball from me sometime.

“I guess on the whole, all the times that I pitched against Ted, I got him out half-decent. But I wouldn’t say I was great, because the son of a gun could hit, man. And he didn’t swing at many curveballs that weren’t strikes. He had to get a strike, you know, and that’s the only way you’re going to get the son of a gun out — you gotta let him hit the goddamn thing, just hope he doesn’t knock it out of the ballpark.”

Notice how Shantz qualified his praise of Williams: he was probably his toughest lefty hitter, he said, but not overall hitter. That, he said, was Roy Sievers, a right-handed slugger for the St. Louis Browns, Washington Senators and others.

In his final season with the Phillies in 1964, Shantz collides with a sliding Hank Aaron at home. (Bettmann / Contributor)

No batter had more runs batted in against Shantz than Sievers, who drove in 17 while hitting .322 with three homers.

“Goddamn Roy Sievers — you have to mention him?” Shantz said. “I couldn’t get that son of a gun out. I don’t know why. I know he was a pretty good hitter, but goddamn, why couldn’t I get him out? He even told me he knew he could hit me. That pisses me off when they tell me they’re goddamn sure they could hit me.”

Shantz said he never chased a repeat of his 1952 success; he simply always believed he would win, no matter how he felt. His career trajectory changed before that miracle year was even finished: batting against Walt Masterson in late September, Shantz took a fastball to his left wrist and broke it.

Shoulder trouble cost Shantz much of the next few seasons, but in family lore, it’s the Masterson pitch that changed everything.

“I once played softball with a relation of his,” Shantz Jr. said. “He said, ‘Well, my uncle was so-and-so and he’s sorry for ruining your dad’s career.’ I said, ‘Oh, that’s nice of him.’”

Shantz persevered, and in his first year with the Yankees, as a swingman in 1957, his 2.45 ERA led the majors. Shantz pitched three times in that year’s World Series and did it again in 1960, including five innings in the middle of the epic Game 7 in Pittsburgh.

The Yankees lost Shantz that winter to the expansion Senators, who then traded him to the Pirates. A year later, another expansion team took Shantz: the Colt .45s, who would become the Astros. Shantz pitched the first game in franchise history, a complete-game five-hitter over the Cubs before a less-than-capacity crowd of 25,271.

“Wee Bobby Shantz, the Houston Colt .45s jack-in-the-box little lefthander, is a mighty big man in the eyes of the Chicago Cubs,” began a story in the next day’s Houston Chronicle. Another piece called Shantz, “no bigger than a bat boy.”

“He may live in Ambler, Pa.,” the paper wrote, “but he’s found a new home here.”

That new home lasted just two more starts. In early May, Houston dealt Shantz to the Cardinals, who would ship him to the Cubs two years later in the infamous Lou Brock-for-Ernie Broglio trade.

“From what I understand, he got traded so quick because the trainer wouldn’t give him the cortisone shot,” Shantz Jr. said. “He was taking a lot of cortisone shots for his pain in his shoulder, and the trainer didn’t want to give him the shots because he was getting too many of them. So they traded him to a team that would give him a shot.”

Pitching, indeed, has always been a painful profession. But when Shantz watches the modern game on television, as he often does, that’s a new standard of strain.

“Christ, those pitchers — I can’t believe they throw that hard!” said Shantz, who pitched long before the radar gun. “Hurts my goddamn arm just watching them. When I see those guys, I don’t think I threw hard at all.”

The hardest-throwing pitcher Shantz faced, he said, was Bob Feller, the Cleveland Hall of Famer who bought two of Shantz’s Gold Glove Awards. (“I think he offered my dad a ton of money for his Most Valuable Player, but he didn’t want to get rid of that,” Shantz Jr. said. “But since he had eight Gold Gloves, he sold him two.”) Yet Shantz never struck out against Feller, going 4 for 12 off him as part of a respectable .195 career average.

“I hit a home run,” Shantz said, laughing, of his lone career dinger. “Allie Reynolds. He’d come over to me, I don’t know where the hell I was, but he said, ‘You little s–––, how did you hit a goddamn home run off me?” I said, ‘I was a pretty good hitter.’ He said, ‘Yeah, you were.’ He was a nice guy.”

Four of Shantz’s eight Gold Gloves remain on display in his home. (Tyler Kepner/The Athletic)

Shantz describes nearly everyone as a nice guy — Brock, Williams, Robin Roberts, Yogi Berra. He was close friends with Curt Simmons, a Cardinals teammate who died in Ambler in 2022. Simmons managed the Limekiln Golf Club with Roberts and would let Shantz play for free.

After his retirement, following a late-season stint with the star-crossed 1964 Phillies, Shantz operated a bowling alley and a dairy bar in nearby Chalfont, Pa., with Joe Astroth, his catcher with the A’s. Another who caught him with the A’s, Shantz’s younger brother Billy, died at age 66 in 1993.

“Goddamn smoking,” Shantz said. “He smoked all the time, and it finally hurt him. Hurt him too much. But he was a good catcher, though. Damn good catcher.”

There are no special plans for his 100th birthday, Shantz said, and no secrets to share about living so long. He knows he’s lucky and said he still feels good. He cannot travel, and often apologizes, unnecessarily, for things he forgets.

Some details, naturally, are lost to time. But for one season, the little man in the easy chair was the greatest player in the American League. The feeling never fades.

“I do think about it once in a while, I really do,” Bobby Shantz said. “I had a great life. Jesus, great life. Boy, I’d like to do that all over again.

“I would love to do it all over again.”

(Top photo of Bobby Shantz at his home in Ambler, Pa. last week: Tyler Kepner/The Athletic)