In the book’s dazzling second chapter, “Black is a Country,” French articulates an intellectual genealogy that begins with crucial 19th-century global figures such as David Walker, Edward Wilmot Blyden, and Africanus Horton. Rejecting the Western philosophical and scientific denigration of Africa as unhistorical and uncivilized, these men crafted political tracts, literary art, and cultural histories that celebrated Africa as “‘the nursery of science and literature’ of Europe.” They recognized Africans and African-descended people as the modern world’s very creators (French’s tremendous, deftly crafted, 2021 history, “Born in Blackness: Africa, Africans, and the Making of the Modern World, 1471 to the Second World War,” is an evidence-rich defense of this claim).

Get Starting Point

A guide through the most important stories of the morning, delivered Monday through Friday.

French reminds us in “The Second Emancipation” that Pan-Africanism and global Blackness were developed to counter the vicious, deadly trans-Atlantic slave trade; the institution of Black enslavement throughout the Americas; anti-Black apartheid in the United States; and the extractive, exploitative, murderous European colonization of the African continent. “The idea of Blackness as a coherent or synthetic identity,” writes French, “only grew out of the European takeover of nearly all of the continent in the wake of the Berlin Conference, which took place in 1884-85 against a backdrop of intense pseudoscientific efforts in late-nineteenth-century Europe to classify the races in terms of their members’ supposed relative physical and intellectual endowments, with Africans fixed at the bottom of a widely postulated hierarchy of races. Empire and imperial science, in other words, changed everything. As the economic historian Immanuel Wallerstein wrote, ‘All European empires in Africa were empires of race.’”

At the first Pan-African Conference in London in 1900, another forefather, W.E.B. Du Bois, brought Pan-Africanism onto the “world stage,” when he announced in his talk, “To the Nations of the World,” that “the problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the colour line.” Among the signal figures who cut different strands of Pan-Africanism throughout the 20th century, French points to J.E. Casely Hayford, Marcus Garvey, Aimé Cesaire, Richard Wright, C.L.R. James, George Padmore, Jomo Kenyatta, Sékou Toure, Patrice Lumumba, and Frantz Fanon. Nearly all these Black radical figures informed or interpolated elements of Nkrumah’s political and ideological positions.

Born “Francis Nwia Kofi Nkrumah” in 1909, the future international statesman came of age in the Gold Coast as Pan-Africanism entered a stage of intellectual and political maturity in West Africa, the Caribbean, North America, and in European metropoles. Nkrumah immigrated to the United States in 1935 to attend Lincoln University, a historically Black institution in Pennsylvania. During the ensuing decade, he acquired degrees in sociology, education, theology, and philosophy. He also ministered to Black American congregants in Baptist and Methodist churches.

When Nkrumah left the United States for Britain, he honed his chops as a political organizer under the tutelage of Du Bois, James, and Padmore. Despite their being unimpressed with Nkrumah initially, he eventually convinced all three theorists that he could lead a decolonized, wholly new, African socialist nation-state. Perhaps this sense of African newness propelled Nkrumah, on the eve of his return to British Gold Coast, in 1947, to begin using “the name familiar to us today, Kwame.”

After another decade of patient organizing, stubborn defiance, imprisonment, and sharp negotiation, Nkrumah would eventually turn Ghana into a model for the “wave of pan-Africanism that seized the continent.” Pan-Africanists were very familiar with Marxism and Marxist theory. However, many of them, including Nkrumah, noted Marxism’s limitations and were generally allergic to Soviet and Chinese modes of communist rule. When the African continent “floated high on the global agenda,” the era of global decolonization, Nkrumah transformed Ghanaian leadership into geopolitical statesmanship, achieving international economic relationships bolstering Ghana’s infrastructure while criticizing, if not resisting, both European neocolonialism and American imperialism.

French’s title refers to this period of desegregation, decolonization, liberation, independence, and massive realignments throughout the Black Diaspora and beyond. From one interpretive angle, global decolonization stretched from 1946 (when the Philippines won independence from US colonial rule) to 1997 (when Hong Kong gained release from British subjection). Zooming in on Africa, the period lasted until Angolans dispatched Portuguese forces in 1975, ending an 18-year-long intracontinental purge of European subjection.

Perhaps the near-decade of Nkrumah’s presidency (1957-1966) is best understood as global decolonization’s second phase and African emancipation’s promising initiation. Nkrumah’s “untold success as a Black statesman required of him not only a vision of nation-building, but also the audacity to speak as an equal with leaders of the world’s established powers: Britain, the United States, the Soviet Union, and France. He had to know when to be malleable and accommodating, and when and how to remain steadfast,” writes French. He became a universal superstar, especially among African Americans who believed he embodied global Blackness’s promise and power.

French charts Nkrumah’s measured triumphs and steep challenges, including the Congo Crisis, which drove the Belgians (with CIA support) to assassinate Lumumba. Blending his lucid, reportorial prose with his expertise in African, Black diasporic, and 20th-century political histories, French produces a dynamic, intricate sequence of documentary nonfiction that rivals Johan Grimonprez’s 2024 documentary, “Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat.”

Unfortunately, Nkrumah was the apogee of decolonial African leadership. “His multiple political priorities and diverse constituencies obliged him to promote Pan-Africanism and nonalignment, while also denouncing European imperialism and South African apartheid,” French notes. Attempting simultaneously to hold neocolonial pressures at bay, perform international statesmanship, and rule the homeland sparked frictive, conflagratory contradictions and a bitter denouement.

Governing as an authoritarian, Nkrumah both launched postcolonial Ghana toward success and failed the nation. Even though he wasn’t a kleptocrat, Nkrumah’s dictatorial style turned Ghanaians against him and encouraged his military leaders to coup d’etat. He was exiled to Guinea until 1972, when he died. Nkrumah’s political demise and early death, French explains, sent African and African American histories into a “new and increasingly divergent phase, one with a less-than-happy ending.” Nonetheless, “The Second Emancipation,” as political and intellectual history, is profound and excellent.

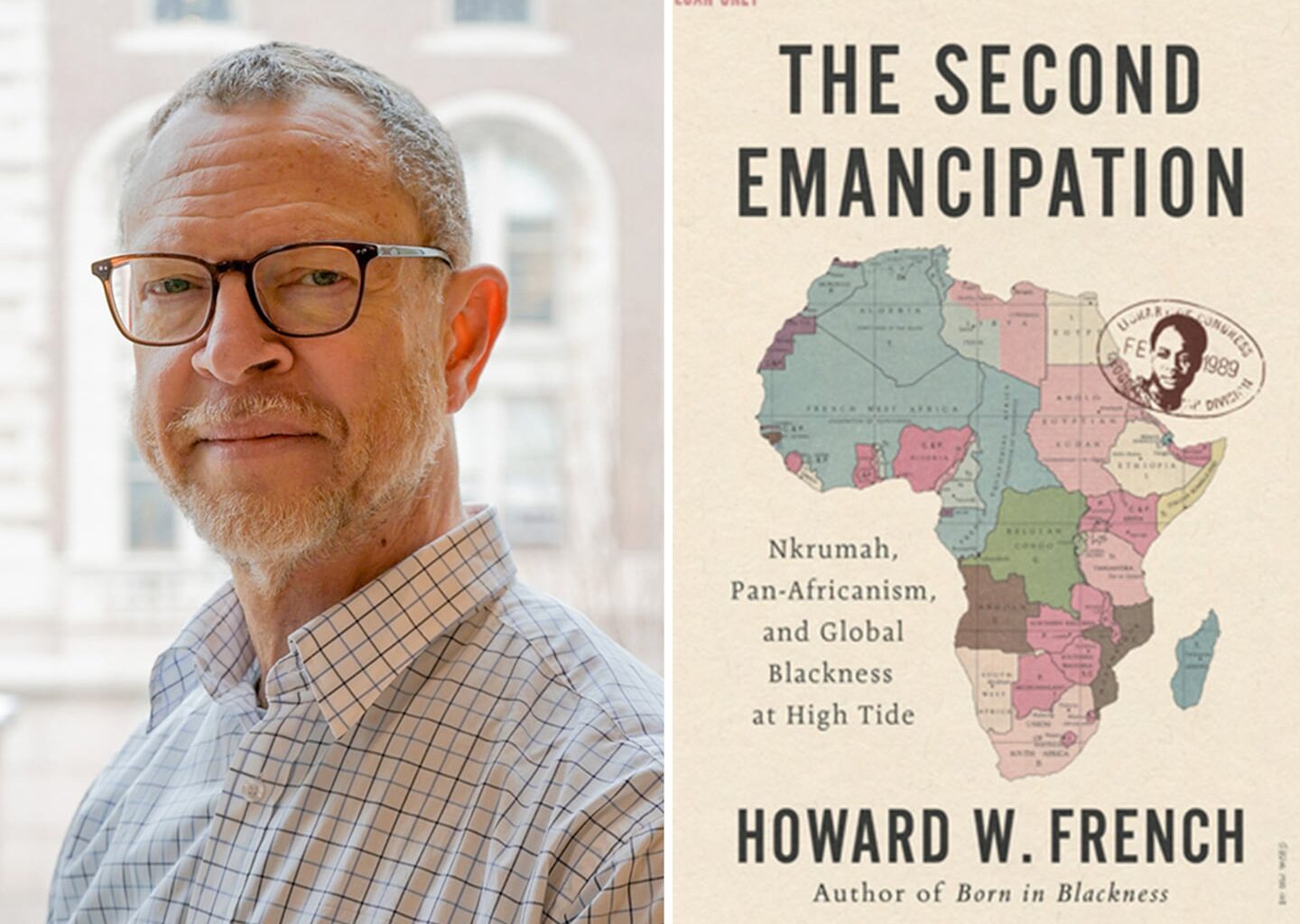

THE SECOND EMANCIPATION: Nkrumah, Pan-Africanism, and Global Blackness at High Tide

By Howard W. French

Liveright, 512 pages, $39.99

Walton Muyumba teaches literature at Indiana University-Bloomington. He is the author of “The Shadow and the Act: Black Intellectual Practice, Jazz Improvisation, and Philosophical Pragmatism.”