‘The problems of financing our deficits have seriously hampered progress in achieving our goals,’ wrote Labour’s chancellor Denis Healey in 1976 in his letter to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Half a century on, little has changed.

Britain’s numbers still don’t add up. Our demographics are the problem: we’re an ageing population with too few taxpayers. As births struggle to replace deaths, liabilities funded from today’s taxes become harder to sustain. If the picture looks bad now, the next few years will be disastrous. A crash seems almost certain.

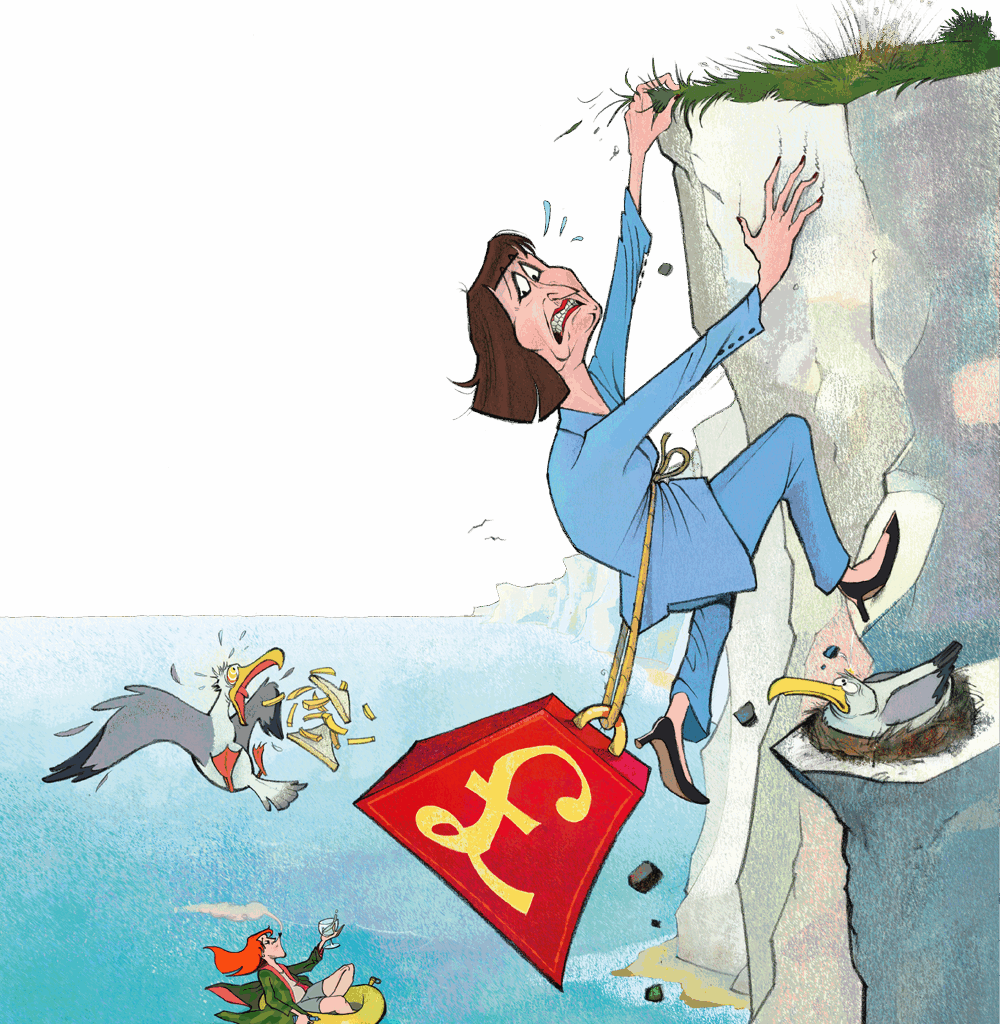

For years the government has spent more than it raises through taxes. It financed that gap through the kindness of others, or to put it more plainly: debt. Staggering amounts of it. Britain owes £40,000 for every person in the country. Every year, another £2,300 per person is slung on. All this adds up to £2.7 trillion – almost the same size as our entire economy – owed to banks, pension funds and foreign governments.

In the past, that debt helped build things: schools, hospitals, roads, runways and train tracks. It strengthened the army and modernised the nation. No more. Increasingly, the government is borrowing not to invest, but to keep creditors at bay. Of the £150 billion we borrowed last year we had to spend £105 billion of it on interest payments – that’s around 4 per cent of GDP and double what we spent on defence.

To borrow money, the Treasury issues ‘gilt-edged securities’, so-named because, when they were first used to fund war with France, the certificates were decorated with gilded edges. Those edges are starting to fray. In recent weeks, the yield (which goes up as debt becomes less attractive to lenders) on 30-year gilts passed 5.6 per cent – the highest in a generation. On Tuesday yields shot up again as the market threw a ‘Torsten Tantrum’ at the news that Torsten Bell, the former head of the left-wing Resolution Foundation, would take charge of economic policy in the run-up to November’s Budget.

‘The market hates Rachel,’ an international bond trader summarises. Rachel Reeves’s defenders argue that rising debt costs are a global trend. True, but Britain’s situation is the worst in the developed world. For the first time, our long-term borrowing costs are higher than America’s. Ten-year gilt yields now sit well outside the G7 range and our debt costs more to finance than supposed ‘basket cases’ such as Spain, Italy and Greece. Worse, when the Bank of England cut interest rates this month, long-dated gilt yields kept rising – something that just shouldn’t happen.

Increasingly, the government

is borrowing not to invest,

but to keep creditors at bay

Part of the explanation for this divergence lies in how British debt is structured. Five years after Healey went cap in hand to the IMF, the Treasury came up with a wheeze to encourage lending. The government would issue index-linked gilts, or ‘linkers’. Rather than just being repaid at face value, they’d rise with inflation. Since they hedged against rising prices, investors loved them and so were happy to buy debt at a discount. Margaret Thatcher’s monetarists loved them too because they incentivised keeping inflation and spending under control. That was the theory, anyway.

But there were always dangers. A Treasury report from May 1981 warned: ‘Indexed gilts will be an expensive form of borrowing if inflation is high, and a profligate government could thereby store up problems for future generations.’ It concluded: ‘Only a government committed to a sustained reduction in inflation would wish to issue them.’

Those conditions have not been met. Profligate government after profligate government gorged themselves on supposedly cheap debt, just as inflation returned. The Treasury’s Debt Management Office (DMO) has £674 billion worth of linkers on the books, which accounts for nearly a quarter of total debt. Including the other public bodies allowed to issue them, such as Network Rail, that figure rises to almost a third.

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) says Britain has the world’s highest share of inflation-linked debt – twice that of Italy, the next biggest issuer. Now that we appear to be stuck with high inflation, that debt has become crippling. In June alone, interest payments doubled to the second-highest monthly bill on record – two-thirds of which came from the ‘capital uplift’ from linkers. Britain now spends more on servicing debt in a single month than on policing our borders in an entire year.

This type of debt also helps explain why Rishi Sunak’s premiership felt so paralysed. Linkers ‘kept Rishi up at night’, one former aide recalls. Each morning, he would log on to his personal Bloomberg terminal to check the debt markets. His obsession with controlling inflation had less to do with the cost-of-living crisis than its effect on Britain’s ballooning liabilities. In cabinet, he was horrified at suggestions that inflation could sweep away debt. Linkers made that impossible.

And yet he kept issuing them. Why? The same former aide tells me Sunak was ‘nervous’ about being ‘seen to influence the DMO too much’, in case his meddling caused a Liz Truss-style market freakout.

The risks caused by our debt don’t stop there. The government’s balance sheet does not include billions in unfunded public-sector pension commitments. If higher interest rates send those liabilities spiralling, debt servicing could overtake not just defence and education – but everything else.

Event

Coffee House Shots Live: Can the Tories turn it around? – Manchester Special

That said, it seems unlikely Britain will take a begging bowl to the IMF – unless Keir Starmer wants to use the prospect to threaten his MPs, as France’s finance minister did this week. Ultimately, the IMF’s member countries are also drowning in debt and simply couldn’t afford to bail us out.

If there’s no saviour, what happens? The worst-case scenario is that the DMO’s weekly debt auctions fail as investors no longer believe that funding our debt is a risk worth taking, forcing massive cuts and tax hikes. But economists agree on three more probable scenarios. Firstly, a market meltdown in the autumn that brings down the government and precipitates a leftward lurch or early election. Secondly, enough good news in time for the Budget that the crash is delayed until around the general election in 2029. Or, finally, prolonged stagnation: no single crisis event, but an economy stuck in a rut and decades of lost growth.

Britain spends more on servicing debt in a single month than on policing our borders in an entire year

The third scenario – where markets give just enough for things to keep limping on – would be the bleakest of them all. It would mean politicians aren’t forced to confront the fact that there are now 700,000 more public-sector employees than before the pandemic and 2.4 million more people on out-of-work-benefits. Or the fact that, long after Covid has passed, total public spending is about five percentage points of GDP higher than it was in 2019, while tax receipts aren’t even two points higher.

In the stagnation scenario, another generation would be condemned to know nothing but slow, methodical decline, wages eaten away by inflation and disposable incomes no better than they were decades ago.

The difficult problem is that democracy not only offers no solution, but makes things worse. Polling from More in Common this month found that 79 per cent of voters regard breaking the promise not to raise taxes on working people as unacceptable while at the same time objecting to spending cuts in the largest departments. The result is that no party dares offer the austerity shock therapy that unserviceable debt demands.

Labour’s successful backbench rebellions over welfare reforms and scrapping the winter fuel allowance for asset-rich pensioners revealed something that markets cannot stand: the government has lost control of its fiscal policy.

Reform, the party on course to form the next government, is promising steel and water nationalisation with no attempt to tackle the debt problem. ‘Nigel knows there isn’t the money,’ a friend of Farage says. ‘But he’s not stupid enough to say it before he’s in No. 10.’ Reform’s plan may be to worry about fiscal problems once they’re in power, but the markets won’t wait. ‘There’s not even a seed of a conversation about what to do with the triple lock or other benefits paid out of current spending,’ complains one investor.

The Tories want to position themselves as the only party willing to be honest about the economy, yet they still fall short of the cuts lenders deem necessary. When Kemi Badenoch was asked recently whether she’d address the biggest cost in the welfare state – the state pension and its triple lock – she dodged the question and merely said her focus was on ‘working-age benefits’.

Inside the Treasury, meanwhile, preparations for Reeves’s second Budget are under way, and officials are jittery. So much hinges on how gilt yields look on the arbitrary date that the OBR locks in its forecasts. If yields spike again, the Chancellor will be in real trouble.

Former officials say she’ll muddle through the Budget: ‘Torsten will find her some revenue raisers,’ one says. But that will buy her months, not years. ‘Then it dawns on everyone: shit, she cannot come back again on tax.’ If borrowing costs and yields keep edging up, Reeves will be faced with yet another crisis in 18 months’ time. What then?

Politically painful though it would be for Labour, it may just be better if Reeves breaks her manifesto pledge and raises taxes on middle earners, who – even though the overall tax burden is at a post-war high – pay the lowest share of tax since the 1970s. Even a one-point increase in the basic rate would raise around £8 billion a year.

Even then, though, we’d still just be buying time. In the long term, the only way out is for politicians and voters to fundamentally rethink what the state should and shouldn’t do. It’s not enough just to slash waste or confront the fact that 6.5 million people are on out-of-work benefits. Unaffordable promises, most notably the pensions triple lock, will need to be abandoned, whatever the political cost.

If politicians fail to face this crisis, debt costs will spiral even more, consumer credit will seize up, the mortgage market will vanish, pension funds will wobble and both government and business will be forced into brutal cuts. Crash or no crash, bailout or no bailout, the reckoning is coming. Pretending otherwise is not just deluded; it is a dereliction of duty.