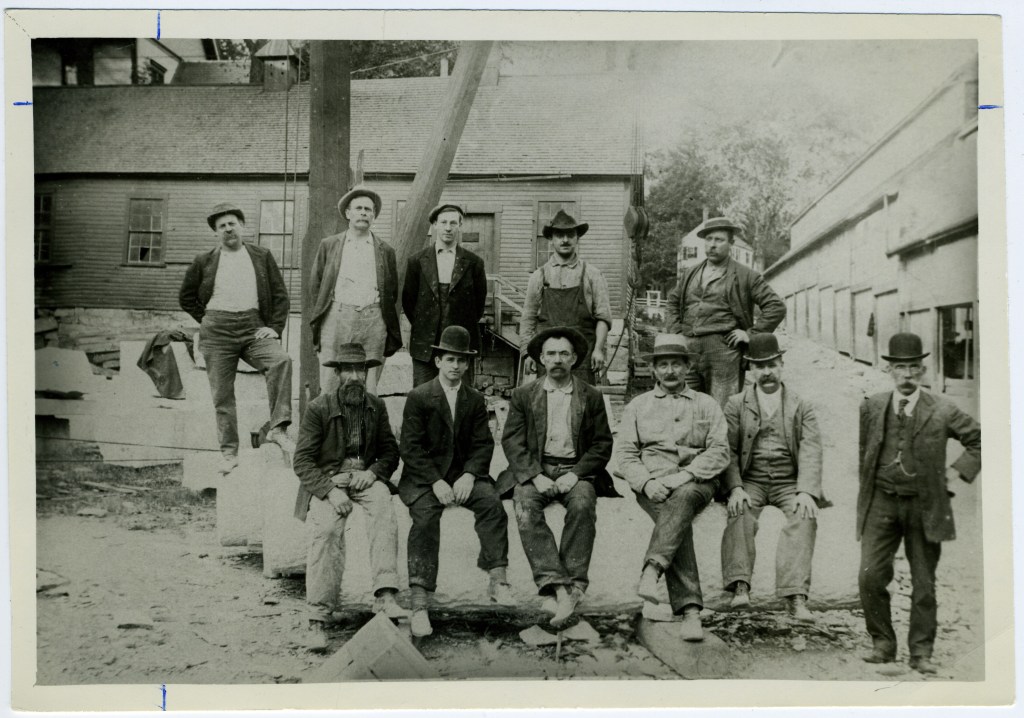

A group of Hallowell Granite Works carvers pose for a portrait in front of a granite shed around 1895. (Courtesy of Collections of Hubbard Free Library)

PORTLAND — The skilled carvers came from an ocean away, eager to work in Hallowell’s granite quarries and build stable lives for their families.

They carved statues, cut stones used to make buildings and chiseled 200,000 cobblestones to be used in Portland. They labored seven days a week in exchange for low pay and crowded housing. Some fell ill with lung disease from breathing in quarry dust.

When the low pay and conditions became too much to bear, their union stood in solidarity and went on strike for more than five months in 1892. They returned with higher pay and better hours, and their work became sought after, prized for its quality and beauty.

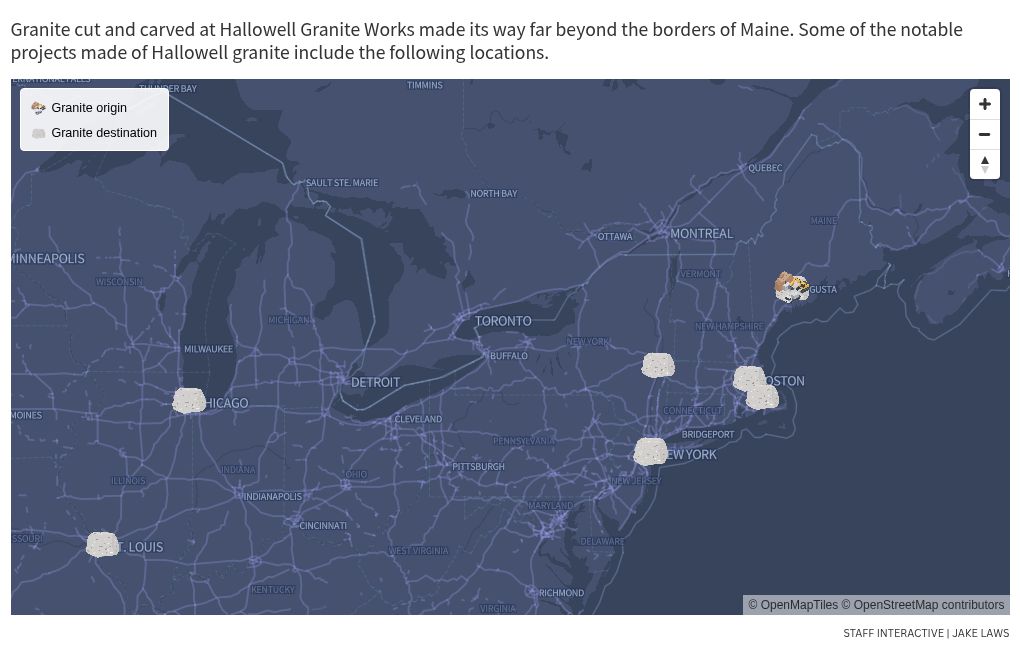

The immigrant workers at Hallowell Granite Works left a legacy carved in granite — their work can still be seen today on landmark buildings both in Maine and far beyond — but the history of their contributions to both the industry and labor movement has largely gone untold beyond the Hallowell area.

A new exhibit at the Maine Historical Society, “Working Granite: Italian Stonecutters and their Union,” highlights one of Maine’s earliest labor unions started by stone workers in 1877. The exhibit focuses on the large community of Italian immigrant stonecutters who settled in Hallowell to work in the granite industry.

“It’s a huge part of Hallowell’s past,” said Bob McIntire, who leads the Historic Hallowell Committee. “But it’s nearly ancient history now.”

No one seems to know exactly how or why the stonecutters made their way from Italy to Hallowell, on the banks of the Kennebec River, starting in the 1870s. They came primarily from Carrara, the area in Italy where Renaissance sculptors like Michelangelo obtained marble, said Tilly Laskey, who curated the historical society exhibit.

“They were really highly skilled, highly trained carvers,” she said. “Once a few people ended up here, a lot more came and then they would bring their families over.”

Cutters from Hallowell Granite Works carve Faith, the central figure of the National Monument to the Forefathers in Plymouth, Massachusetts, in 1877. (Courtesy of Collections of the Hubbard Free Library

By 1901, more than 3,500 American and immigrant stonecutters were laboring in 152 quarries across the state. These skilled carvers transformed Maine granite into statues, buildings, bridges, headstones, cellars and pavers, according to the historical society.

At its peak in 1901, the state’s granite industry ranked first in the nation for sales. That year, the industry’s reported earnings were $2.5 million, the equivalent of over $119 million today. After World War II, the industry declined in the wake of new stone cutting technology, changing architectural styles and easier access to steel and concrete.

But before all of that, the Italian stonecutters in Hallowell carved out their own unique mark on the industry.

FROM ITALY TO MAINE

The Longfellow Quarry is one quarry where granite was mined on Granite Hill in Hallowell. The quarry off of Winthrop Street was abandoned following the rise of steel as a building material. “They no longer needed to pile big granite blocks on top of each other in order to build buildings,” said Bob McIntire, chair of the Historic Hallowell Committee. (Daryn Slover/Staff Photographer)

Laskey first heard about Maine granite and the stonecutters years ago through an exhibit at the Hubbard Free Library in Hallowell, a building made of granite from the local quarries. She had spent time in Carrara and thought about how those Italian stonecutters ended up in a small town in Maine.

“I’ve always wondered why so many Italians gravitated here,” sh e said. “I think it had to do with the fine granite that they could actually make carvings out of.”

Hallowell granite was desired for its high quality. It was light and fine-grained, with a high percentage of feldspar that made it easy to work with in the quarry and with a chisel. It was almost as white as marble and, when polished, glittered like diamonds. Its appearance made it especially sought-after for statues.

Granite was quarried commercially in Hallowell as early as 1815, with some of the stone quarried from Hains Ledge on Lithgow Hill being shipped to Boston for the cornice stones of Quincy Market. It was also used to build the Maine State House, Kennebec Arsenal and the Maine Insane Asylum in Augusta, according to a history of Hallowell granite written by state historian Earle Shettleworth Jr.

Large-scale quarrying didn’t begin until 1865 when Joseph Bodwell founded Hallowell Granite Company, which reorganized as Hallowell Granite Works 20 years later. Bodwell — a two-term Hallowell mayor, state representative and governor — had opened granite quarries on Vinalhaven in 1852.

A granite carving of a sturgeon at Granite City Park in Hallowell was created by Jon Doody. The sturgeon was carved from a one-ton block of Hallowell granite. (Daryn Slover/Staff Photographer)

The Hallowell Granite Works stone yard, located on the west side of Franklin Street, was surrounded by three stone cutting sheds, a power plant and an office.

Despite operating quarries in two communities, it was only Hallowell that drew Italian immigrants, Laskey said.

Laskey said immigrants who had been in the area longer worried the Italians would be “birds of passage” — people who would come in to work for lower wages, then leave for other opportunities — but that’s not what happened. Once the Italian men were settled into their new jobs, they often brought their families over from Italy to join them.

Bob McIntire, right, chair of the Historic Hallowell Committee and retired Hallowell City Historian Sam Webber stand next to a quarry crane at Granite City Park in Hallowell. The crane and many more like this one were used to lift heavy granite stones in the quarries on Granite Hill. (Daryn Slover/Staff Photographer)

Photos in the historical society exhibit capture a bit of the daily lives of the Italian families who lived in a small community that sprung up around the quarries. Lasky, building on the earlier exhibit in Hallowell, obtained photos from descendants of the workers and from Sam Webber, Hallowell’s retired city historian.

The families lived in company housing and their children attended the Warren Street School, which became an integral part of the Italian neighborhood.

Among the skilled carvers living in the neighborhood was Protasio Neri, who immigrated to Maine from Levigliani, Italy, in 1877 at age 27 to begin working at Hallowell Granite Works. He had worked in the quarries near Carrara and studies with Professor Moreschalchi, an architect at the University of Carrara.

A year after he arrived in Hallowell, Neri had saved enough money to bring his wife and two children to Maine. His daughter Amina was one of the first Italian children born in Hallowell.

By 1889, Hallowell Granite Works reported 330 workers, including 100 quarrymen and more crews of stonecutters and carvers. That year, the Maine Bureau of Labor noted workers at the company included 76 Americans, 62 Italians, 15 English, five Canadians, three Irish and one Scots.

At Arche’s quarry near Hallowell, 90% of the 45 men carving stone for the Maine State House were Italian and Scottish immigrants. There were no Italians working at granite quarries at Vinalhaven, Spruce Head, Belfast and West Sullivan, where workers were American, Scots, English, Canadian and Irish.

THE GREAT STRIKE

While the Italian stonecutters were recognized for their skill, the success of the granite industry didn’t equate to higher wages for carvers and quarrymen.

“In the Gilded Age, you have these very wealthy people who own the companies, but that wealth isn’t trickling down to workers,” Laskey said. “They were working 12 hours a day, seven days a week.”

A granite carving at Granite City Park in Hallowell was created by Mark Herrington. “Flowing Through”was carved from several pieces of Hallowell granite. (Daryn Slover/Staff Photographer)

Companies provided housing and stores for workers, but deducted rent, food and supplies directly from their paychecks, often leaving workers in debt and beholden to their employers.

Working in the quarries was dangerous and sometimes led to lung disease. McIntire, from the Hallowell Historic Committee, pointed to the work it would have taken to fill an order for 200,000 cobblestones.

“People sat day in and day out carving cobblestones. Some got respiratory diseases that really took a toll, to say nothing of their hands,” he said. “It was tough stuff to sit there and carve granite blocks all day long.”

By 1892, the workers in Hallowell grew frustrated that they weren’t getting paid enough and decided to take action.

They were members of the Granite Stonecutters Union, which was started in Rockland in 1877 with the goal of establishing uniform rates and improving conditions. A decade later, stonecutters, carvers and blacksmiths from Hallowell joined the union.

Protasio Neri poses for a portrait around 1892. (Courtesy of Kelly Arata)

In May 1892, workers at Hallowell Granite Works joined 12,000 union members in a regional labor strike that last five and a half months.

During the strike, Hallowell Granite Works evicted workers from company housing to pressure them to return to their jobs. That didn’t work, so the company hired 25 non-union quarrymen from Boston. But a July 17 article in the Portland Evening Express noted “the large shed where hundreds of men are generally employed is closed” because union representatives convinced the men from Boston to stop working.

Neri, the Italian carver, became a labor leader and wrote updates about the strike in an Italian newspaper that was distributed to workers across New England.

Ultimately, the union was able to secure better wages and conditions. When Hallowell Granite Works settled with union employees on Oct. 20, 1892, the Kennebec Journal reported there was “much rejoicing in the city over the settlement … and Hallowell may well be pleased at the assured prospect of hearing the sound of a hammer once more.”

By 1901, carvers at Hallowell Granite Works averaged between $2.80 and $3.20 in wages per day, while quarrymen earned $1.75 to $2 per day. That’s a range of $53 to $96 per day in 2025.

The business boomed from 1904 to 1906 when hundreds of statues, columns and monuments were sent all over the country, but began to decline soon after as concrete became a preferred building material. The quarries in the region were abandoned by the mid-1900s

Today, Hallowell reports about 9% of its population is Italian American, showing the legacy of the first-generation Italian stonecutters.

Copy the Story Link