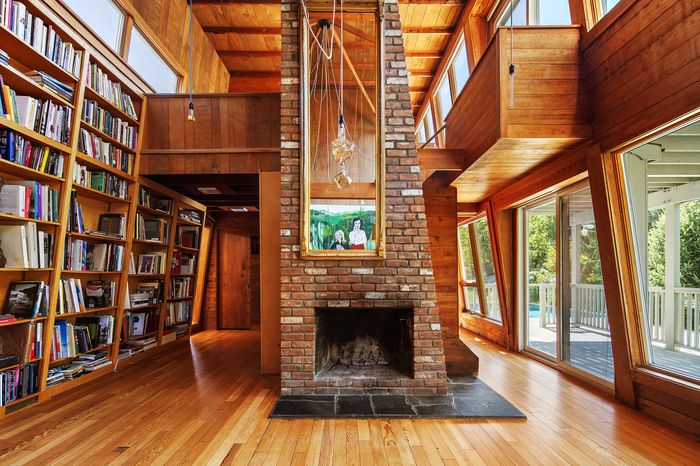

Geller’s houses are “people-centric,” said broker Esteban Gomez. “They’re not precious. It’s completely a work of art, but it’s also a home.” To the right is a painting by Becky Kolsrud. The lamp was made custom to fit the space by one of its owners.

Photo: Alejandro Leon/DDReps

The curator Alison Gingeras bought the house at 55 Knollwood Lane for the same reasons she might buy a work of art: rarity, condition, and sheer delight. She had learned about the architect Andrew Geller in her studies of 20th-century art history, and his name stuck out as she was scrolling the internet absentmindedly in the summer of 2020. The future felt uncertain. Her husband, the artist Piotr Uklański, couldn’t get into his studio in Greenpoint and was painting in their Brooklyn rental. Why not look at a house? And not just any house — maybe the only house Geller ever built on the North Fork, where the family had friends and where their kids could enroll in school. “We weren’t even planning on buying a house and moving out of the city,” said Gingeras. “We just kind of went for it.”

A view from the circular driveway.

Photo: Alejandro Leon/DDReps

Through the 1960s, Geller worked in the familiar modernist palette of raw wood and glass, but he had a reputation for whimsical, almost goofy homes that earned silly nicknames from his wife, Shirley Geller. She “had a kind of knack for naming,” remembered her grandson, Jake Gorst, who wrote a book on his grandfather’s work. There was the so-called Grasshopper House, with its jutting leggy wings; the Milk Carton house, which balanced along one long, thin edge; and the Double Diamond, a pair of cubes that sat side by side on points. The houses were warmer than sleek modernist boxes, “little dream houses that inspired self-expression and personal freedom,” per the critic Alastair Gordon, who revived interest in Geller after including him in a 1987 exhibition. Gordon and Geller then drove around Long Island rediscovering all of his creations. “They were so fresh, so alive, so joyous and fun and inexpensive,” Gordon said on the phone this week. “He rarely repeated himself.” The homes were also built on a budget for other middle-class New Yorkers: The 1957 commission that made his reputation, built for a co-worker at the industrial-design firm Raymond Loewy, went up for $7,000, or $80,000 today.

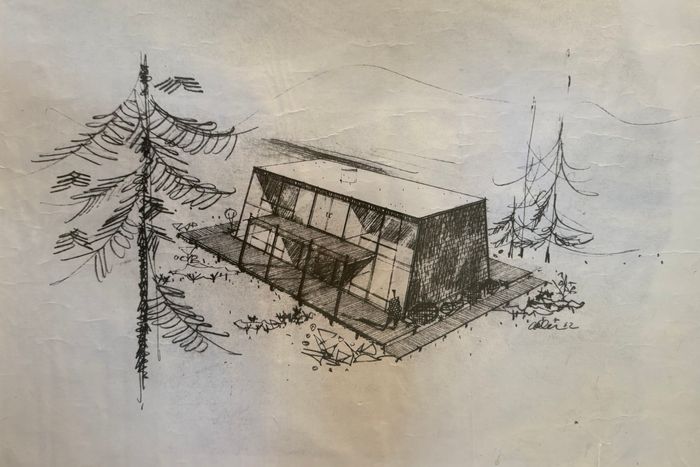

A Geller drawing for the 1962 house shows the “toaster” shape and the double balcony.

Photo: Courtesy Alison Gingeras

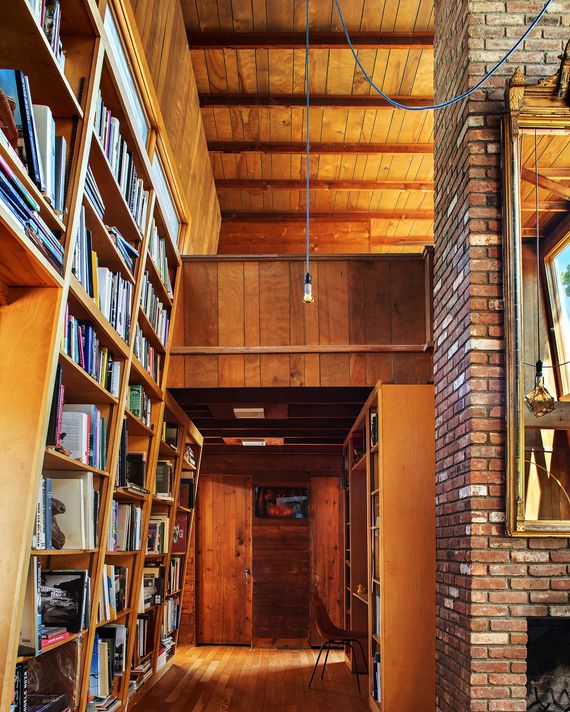

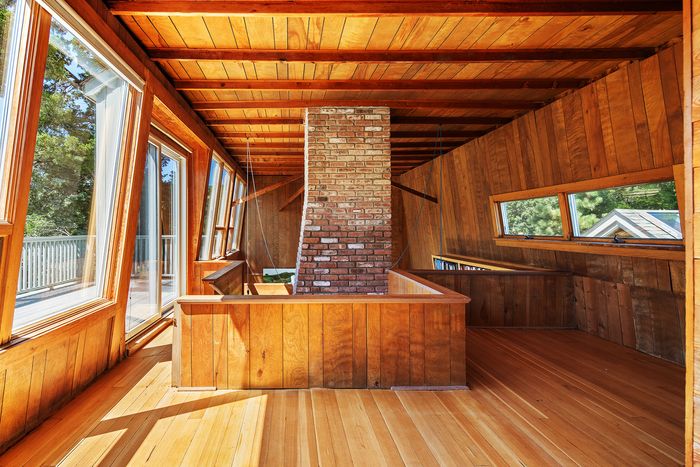

The house that Gingeras snapped up in 2020, an A-frame with a flat, truncated top, was nicknamed the Toaster House. As the walls slope up gently in the double-height great room, there’s room for built-in bookshelves below high windows on one side and a wall of glass on the other. Rising through the center is a simple brick fireplace, backed by a stair that rises to a sleeping loft with its own balcony, and walls, floors, and ceiling of the same honey-toned wood. The house was built in 1962 for Ira P. Schneiderman, a department-store market analyst who may have known Geller through Loewy, where he worked days designing malls and Lord & Taylor stores. Schneiderman and his wife, Mona Weinberg, a public-school teacher with an artistic streak who taught guitar and piano on the side, sold in the late 1960s to Aurelie Dwyer, another artsy professional with bold style. She worked as a fashion illustrator before a career as an editor at Newsday. She had long admired Geller’s designs but didn’t realize she was buying one until she was closing on the house. “I thought, This is magic,” she told Gorst when they chatted for his book.

The house was named after the form of a vintage toaster that opens on the sides.

Photo: Courtesy Alison Gingeras

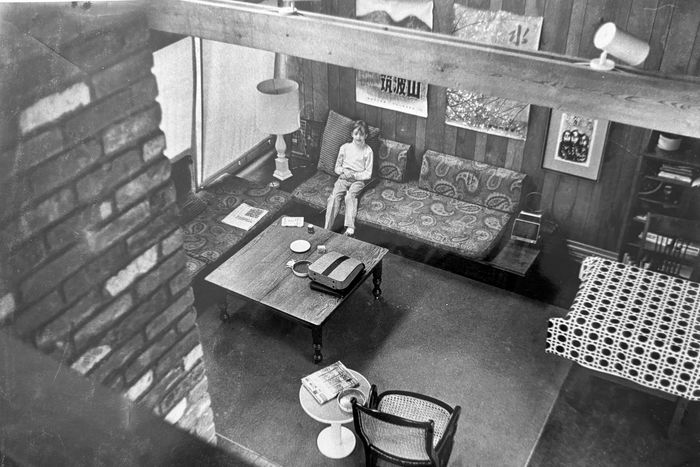

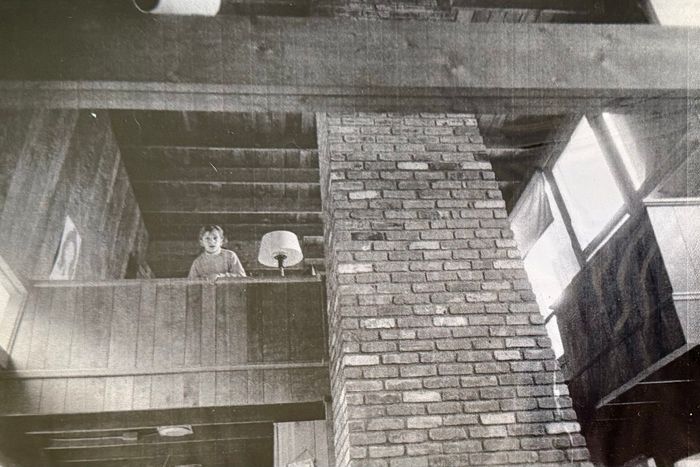

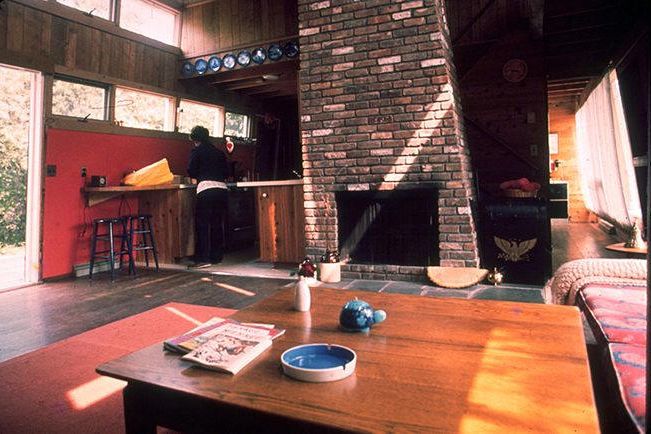

A photo from the Dwyer era that was gifted to Gingeras when her family closed on the house.

Photo: Courtesy Alison Gingeras

The view up toward the sleeping loft remains unchanged.

Photo: Courtesy Alison Gingeras

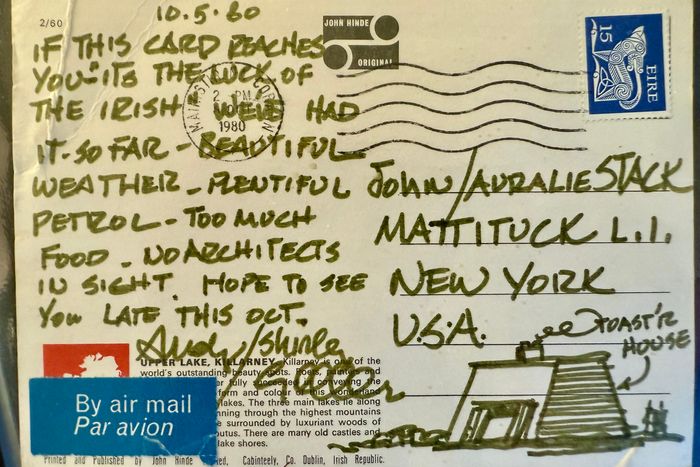

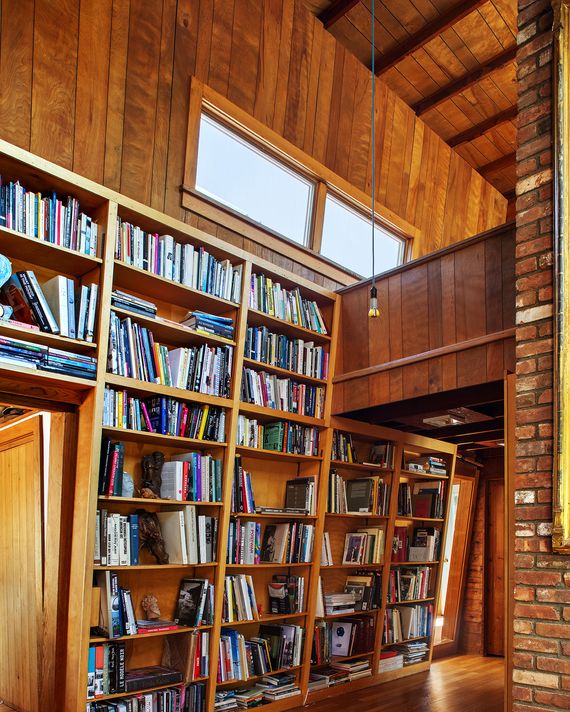

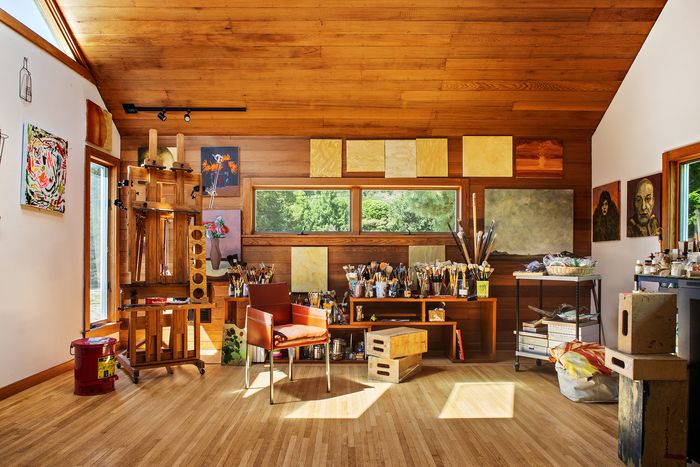

When Dwyer and her husband, John Stack, decided to live on Knollwood Lane full-time, they enlisted Geller to add a new wing off the original “Toaster,” turning a one-bedroom into a four-bedroom, expanding an old kitchen, and customizing the fourth room to serve as Stack’s painting studio. Geller also added more built-ins to house an editor’s library. After Dwyer died in 2011, the estate sold to Maribeth and Thomas Edmonds, the latter then a director at Southampton History Museum, who took care to preserve Geller’s work. By the time Gingeras toured through in 2020, she was “amazed” at the condition of the home: Everything was intact, even a Geller-designed rack for drying canvases in the painting studio. “It’s almost like this 1960s film set for a painter.”

A postcard from Geller to the Stacks when the renovation was in planning stages. “He became friends with most of his clients,” says Gorst.

Photo: Courtesy Alison Gingeras

Gingeras put her thousands of reference books on the shelves Dwyer had built. Uklański used the studio for his paintings and works outside in the warmer months. Their art went up. The kids enrolled in school in Mattituck. And the new pandemic project became redoing the exterior: adding a wildflower garden, putting in a pool, painting a deck, and adding pine trees to bring in shade and privacy. In the kitchen, they replaced a tile floor and switched out cream countertops for butcher block that matched the cabinetry Geller had designed. A drawer off to one side of the stove turned out to have inserts for holding spices. “It was this perfect minimalism,” Gingeras said. “We were like, We’re not touching anything.”

Price: $1.5 million ($9,608 annual taxes)

Specs: 3 bedrooms, 3.5 bathrooms

Extras: Pool, deck, roof-deck, flower garden

10-minute driving radius: Breakwater Beach, the Old Mill Inn, Hallock State Park Preserve

Listed by: Eric Elkin and Esteban Gomez, Compass

The entryway frames a painting by El Hadji Sy. Turn right to enter the 1962 wing, with a double-height living area, a sleeping loft, and a deck to the pool. Head left to go to the 1982 wing.

Photo: Alejandro Leon/DDReps

The living room is just a few steps off the foyer, through the door pictured here. Past the foyer is the 1982 wing that Geller designed for Dwyer and her husband, John Stack.

Photo: Alejandro Leon/DDReps

The sloping walls of the 1962 “toaster.” There’s a sleeping loft above, and a downstairs bedroom down the hall to the right, with views over a recently installed pool.

Photo: Alejandro Leon/DDReps

The living area back when an ashtray counted as a centerpiece, and the built-ins hadn’t yet been installed.

Photo: The Estate of Andrew Geller/ Courtesy of Mainspring Archive and the Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture

The clever shelving was built by Geller for Aurelie Dwyer Stack, the home’s second owner, a Newsday editor with a sprawling library who was known as a stickler for grammar, sometimes wearing a T-shirt that said, “I am the Grammarian about whom your mother warned,” according to an obituary.

Photo: Alejandro Leon/DDReps

A built-in desk below the sleeping loft is tucked into Dwyer’s built-ins.

Photo: Alejandro Leon/DDReps

The downstairs bedroom in the 1962 wing.

Photo: Alejandro Leon/DDReps

The fireplace mirrors the gentle slope of the exterior “toaster.” Stairs lead up to a sleeping loft.

Photo: Alejandro Leon/DDReps

Looking down into the living area from the loft.

Photo: Alejandro Leon/DDReps

The stairs up to the sleeping loft land at a door to the upstairs balcony. Turn left, however, and there’s a quiet enclosed bedroom that Gomez, the broker, says feels like sleeping in the hold of a ship.

Photo: Alejandro Leon/DDReps

Photo: Alejandro Leon/DDReps

The downstairs bath (left) and an en-suite bath off the sleeping loft (right) are Geller originals. Alejandro Leon / DDReps.

The downstairs bath (left) and an en-suite bath off the sleeping loft (right) are Geller originals. Alejandro Leon / DDReps.

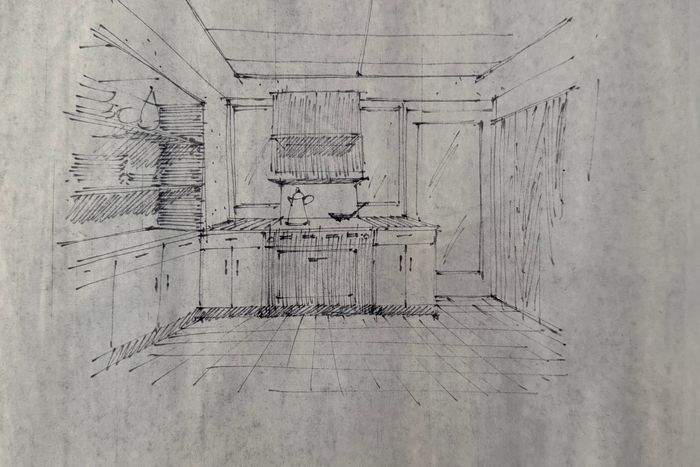

The updated kitchen that Geller concocted in 1982 is relatively unchanged. The current owners switched out Formica countertops for butcher blocks but retained Geller’s cabinetry, whose proportions are “perfect,” Gingeras said. “Someone who designed this kitchen knows how to cook.”

Photo: Alejandro Leon/DDReps

Geller’s drawing for the 1982 kitchen shows a chef’s stove with a salamander.

Photo: Courtesy Alison Gingeras

A listing photo from 2012 shows the stove is still there, as well as the cream-colored tile and Formica countertops that Gingeras and Uklański replaced.

Photo: The Corcoran Group

The artwork under a cabinet is by Bernard Buffet. Through the kitchen is a downstairs bedroom that the owners have been using as an art studio.

Photo: Alejandro Leon/DDReps

A downstairs bedroom off the kitchen has been used as an art studio, too.

Photo: Alejandro Leon/DDReps

A view of the studio downstairs.

Photo: Alejandro Leon/DDReps

The downstairs studio.

Photo: Alejandro Leon/DDReps

Off the entrance to the home, to the left, is the 1982 wing. Stairs lead up to an art studio that Geller designed, and a hall leads to the primary bedroom.

Photo: Alejandro Leon/DDReps

The primary bedroom.

Photo: Alejandro Leon/DDReps

The bathroom off the primary bedroom, with the same simple cabinetry that Geller used in the kitchen: wood with brass handles.

Photo: Alejandro Leon/DDReps

The studio that Geller built for John Stack on top of the new wing included a storage loft, and a door leads to a flat section of roof between the two wings, where Uklański sometimes painted outside.

Photo: Alejandro Leon/DDReps

Doors off the upstairs studio lead to a roof-deck.

Photo: Alejandro Leon/DDReps

A door off the painting studio leads to a roof-deck over the entrance, where Uklański could paint outside.

Photo: Courtesy Alison Gingeras

The upstairs studio also has a half-bath through the door (left) and storage that seems designed to hold canvases for drying.

Photo: Alejandro Leon/DDReps

The studio half-bath, convenient for a painter who needs to wash brushes.

Photo: Alejandro Leon/DDReps

Geller’s double deck for the 1962 house.

Photo: Alejandro Leon/DDReps

The pool sits off the original wing. It was added by Gingeras and Uklański, who were careful to build with simple, exposed materials that Geller would have endorsed: raw concrete and a wood deck that matches the rest of the house.

Photo: Alejandro Leon/DDReps

The owners added pines around the border of the pool to make it feel more private.

Photo: Alejandro Leon/DDReps

Uklański designed a concrete retaining wall (right) at the end of the new pool. Steps down lead into a lush garden, where Gingeras planted wildflowers.

Photo: Alejandro Leon/DDReps

Sign Up for the Curbed Newsletter

A daily mix of stories about cities, city life, and our always evolving neighborhoods and skylines.

Vox Media, LLC Terms and Privacy Notice

Related