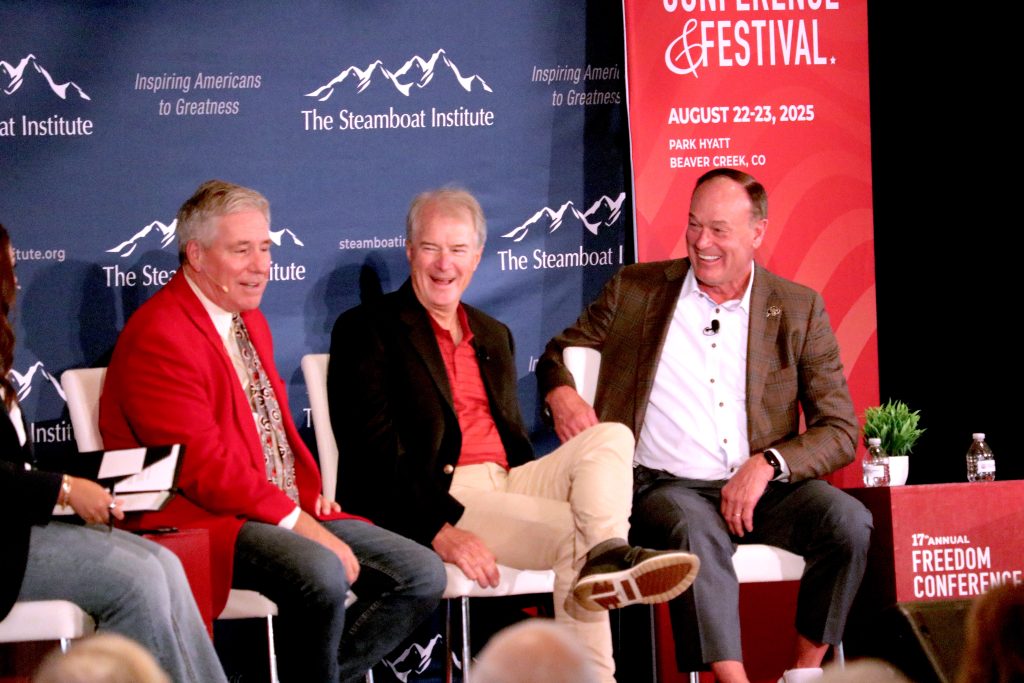

From left: Daniel Mitchell, Mark Stevens and CU athletic director Rick George share a laugh during the Freedom Conference in Beaver Creek last Saturday.

From left: Daniel Mitchell, Mark Stevens and CU athletic director Rick George share a laugh during the Freedom Conference in Beaver Creek last Saturday.

Ryan Sederquist/Vail Daily

Last Saturday, University of Colorado Boulder athletic director Rick George and Buff’s coach Tad Boyle were joined on stage by economist Dan Mitchell and Golden State Warriors executive board member Mark Stevens to discuss the future of college sports in the NIL era at The Steamboat Institute’s 17th-annual Freedom Conference.

A full house at the Park Hyatt in Beaver Creek watched moderator Amber Duke guide the conversation from the recent NCAA House settlement to topics like the transfer portal, the future of non-revenue sports’ support of the Olympic pipeline and even Instagram superstar Livvy Dunne.

“College athletics has changed dramatically and it’s going to continue to change,” George said early in the 60-minute panel.

The two-day Freedom Conference offered attendees the chance to listen to and ask questions of nationally recognized conservative thought leaders. Other notable guests included Fox News chief political anchor Bret Baier, U.S. Secretary of Energy Chris Wright and Emmy-Award winning sportscaster Michele Tafoya.

The 11 a.m. panel titled “The Future of College Sports in the Age of NIL and Player Compensation” opened with a question surrounding the House v. NCAA settlement formally approved in June. The $2.8 billion agreement — which claimed the NCAA was illegally limiting the earning power of college athletes — paved the way for schools to start cutting checks to athletes. In the first year, each school can share up to about $20.5 million with its athletes, a number that represents 22% of their revenue from things like media rights, ticket sales and sponsorships, according to the Associated Press.

Support Local JournalismDonate

“You think about what that does to a budget at a power-5 athletic department — that’s a huge new line item that schools are going to be scrambling to cover,” Stevens said. “It’s causing a lot of turbulence in college sports right now.”

University of Colorado Boulder head men’s basketball coach Tab Boyle listens as moderator Amber Duke poses a question to the panel during the 11 a.m. session, “The Future of College Sports in the Age of NIL and Player Compensation.”Ryan Sederquist/Vail Daily

University of Colorado Boulder head men’s basketball coach Tab Boyle listens as moderator Amber Duke poses a question to the panel during the 11 a.m. session, “The Future of College Sports in the Age of NIL and Player Compensation.”Ryan Sederquist/Vail Daily

College athletes have been getting paid since the NCAA cleared the way for them to receive name, image and likeness (NIL) money from third parties in 2021. Under the new settlement, schools can now also pay money directly to athletes. The convergence of new TV deals with NIL revenue sharing has increased the prevalence of the transfer portal. George said 30% of the football teams playing this Friday weren’t here for spring practice. In women’s basketball, he said 80% of the roster turned over.

“We’re seeing student-athletes go to three or four or five different schools in their career,” the athletic director said. “That’s not healthy. … We have to remember that the education of our students is paramount.”

“I think it’s going to become frustrating for fans,” said Boyle. “I don’t know how you can play an efficient game of football or basketball when you’ve had very limited time to coach these kids and there’s been no culture to build up.”

“Right now we have totally unrestricted free agency in college sports,” Stevens added. “We have free agency in pro sports, but there’s a lot of rules around it. I feel very sorry for Tad and coaches around the country because you have basically a new roster every year.”

George said one problem is that “as soon as we create a rule, we try to circumvent the rule.”

“That’s why we do need some kind of limited protection because we can’t self-govern ourselves,” he argued. “Historically, it hasn’t happened.”

Attendees of The Steamboat Institute’s 17th-annual Freedom Conference listen to a panel discussion on the future of college sports in the age of NIL and player compensation at Beaver Creek on Aug. 23.Ryan Sederquist/Vail Daily

Attendees of The Steamboat Institute’s 17th-annual Freedom Conference listen to a panel discussion on the future of college sports in the age of NIL and player compensation at Beaver Creek on Aug. 23.Ryan Sederquist/Vail Daily

While the House v. NCAA agreement eliminates sport-specific scholarship limits, it comes with a catch: roster limits. This poses a unique threat to non-revenue sports, since a football scholarship and say, a track scholarship, cost the same for a school — but only one of those sports makes the university money.

“It’s a real issue if school’s start dropping sports,” said Stevens, who is on the U.S. Olympic Committee Foundation board. “There’s a lot of concern that if power-5 schools start dropping their non-revenue sports because of budget issues, that’s going to impede our Olympic teams going forward.”

At the 2020 Summer Games, 75% of Team USA’s Olympians were college athletes, including 100% of the rowing, basketball and volleyball squads, 95% of the track team and 91% of the swim roster. A similar percentage of college athletes made up the 2024 group, which — for the eighth-straight Olympics — led the U.S. to the top of the medal count table.

At the University of Colorado, football and men’s basketball drive 81% and 13% of the athletic budget’s revenue, said George, who added that CU is navigating the new revenue sharing model by sharing “based on the revenue the teams bring into the department.”

“But the executive order was really important,” George added. “Because I think the voice that’s been missing this whole time with all these changes going on is the Olympic movement.”

President Donald Trump’s “Saving College Sports” executive order moved to protect women’s and Olympic sports by establishing benchmarks for scholarships based on an athletic department’s income.

“The idea was that the revenue generated from college athletics, the big sports — football, basketball, etc. — was used to then have other programs,” said Duke, senior editor at The Daily Caller. The question is, will there be enough money to finance revenue sharing payments and still support non-revenue programs? George believes the answer could be the SCORE Act, a bipartisan bill he said “needs to happen.”

The bill, introduced by Democratic Reps. Janelle Bynum, from Oregon, and Shomari Figures, from Alabama, with Republicans on July 10, intends to “protect the name, image, and likeness rights of students athletes to promote fair compensation with respect to intercollegiate athletics, and for other purposes.” Amongst other impacts, CBS Sports reported it would lead to the “establishment of federal standards for NIL, regulations for agents representing college athletes, preventing universities from revoking scholarships due to injury or performance.” It would also mandate schools to have a minimum of 16 varsity teams.

During the audience questionnaire portion of the conversation, George was pressed on how he divides the cap pie between his sports.

“Do you find yourself telling Tad ‘no’ so you can tell Deion (Sanders) ‘yes’ and vice-versa?” Duke asked.

“All of the above,” George said before adding that he has had “up-front conversations” with coaches individually and the department as a whole.

“Our emphasis is going to be on football and men’s and women’s basketball,” he said. “And we’re not going to take away anything from other sports and we’re going to provide the same benefits. And I said this to our student-athletes as well because that’s a reality of our situation.”

Livvy Dunne and life after college sports

Duke brought up the pre-NIL argument of some who viewed collegiate athletes as being taken advantage of by universities for their talent.

“But now I worry about a different type of exploitation,” she said. Duke pointed to LSU gymnast and social media influencer Livvy Dunne. In May 2023, the 22-year-old had an estimated NIL valuation of $3.3 million, the highest value of any women’s college athlete at the time.

“Let’s be honest, she looks good on Instagram,” Duke said. “Is that just a new form of exploitation?”

George said the difference is that athletes now “are making money.” At CU, student-athletes also receive education on financial literacy and brand development, he said.

“My concern is, you have some of these players making 50, 60 maybe $100,000 … only 1% go to the NFL and it’s probably less than that in basketball, so they’re probably going to have to take a pay cut when they’re done playing college athletics in the sports of football and basketball,” he said. “To me that’s an issue, and if you don’t have an education and didn’t get your degree, you’re going to go into the new world with a real challenge.”

While there wasn’t a lot of back-and-forth banter between the four panelists, nor were tangible solutions explored with great depth, each was asked to pick one regulation they thought would be most important to preserving the health of college sports moving forward. Mitchell believed schools, conferences and the NCAA ought to come together to figure out rules on their own — without the federal government’s involvement. Stevens, Boyle and George felt the focus should be on the free agency issue.

“We’ve got to figure out a way that’s reasonable that slows down the year-after-year transfers but still gives the student athlete the ability to move up or move down based upon their specific situation,” Boyle said.

“I think what we’re losing sight of is the educational piece of the student-athlete and we’ve got to get back to that,” said George. “So we need to put some rules and regulations in place that ensure these young men and women get their education.”