Raymond Antrobus, poet

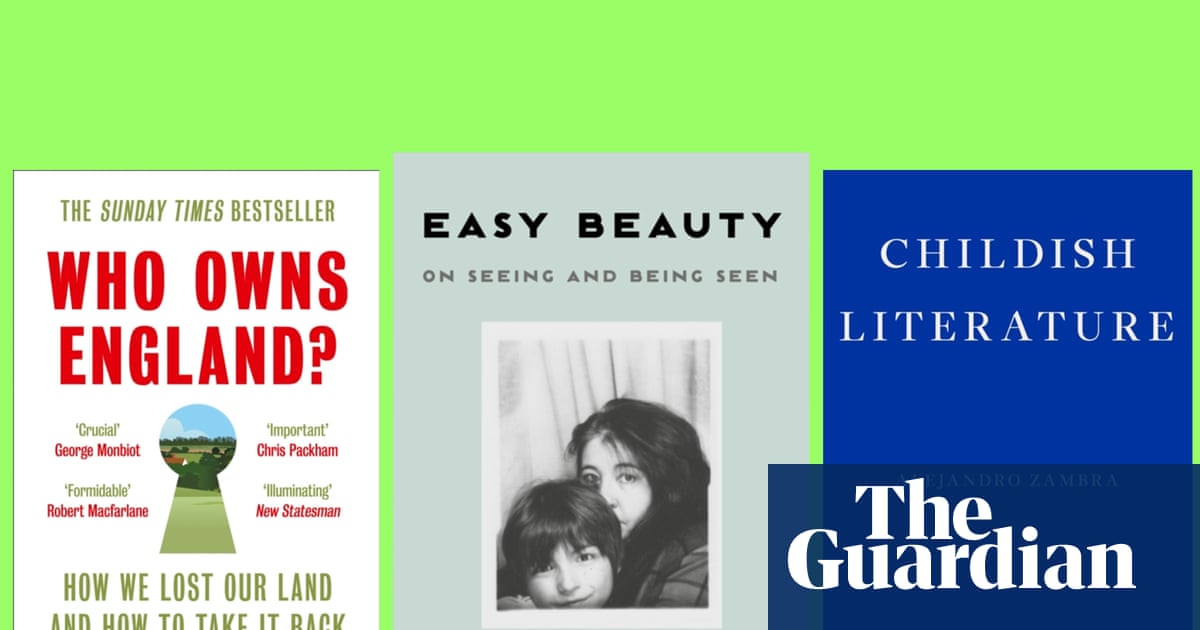

One of my favourite reads recently has been Childish Literature by Chilean author Alejandro Zambra, translated by Megan McDowell. It’s a mixed-genre book of memoir, short fiction and poetry on the theme of parenting and new fatherhood, with lots of lucidity, humour and humility throughout.

To 2049 by American poet Jorie Graham is one of my favourite collections of recent times and rereading it recently was incredibly rewarding. Filled with slippery and existentially evocative lines such as “Years pulled their / lengths through us like long wet strings”, it had me pointing at some of the pages gasping: “I wish I wrote this!” (a condition I frequently suffer from, known as poem-envy).

Another poetry collection I recently enjoyed is The Island In The Sound by Scottish poet Niall Campbell. Campbell writes concise, soulful and lyrically observant poems that are (subtly) apocalyptic and (sonically) beautiful.

Easy Beauty by Thai American author Chloé Cooper Jones is one of my favourite memoirs by a disabled author in recent years. It’s impressively scholarly, emotionally honest and very giftable for students, readers and writers looking for more nuanced disability narratives.

The Quiet Ear by Raymond Antrobus is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson. To support the Guardian order your copy from guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.

Michael, Guardian reader

I finished Is a River Alive? by Robert Macfarlane over the weekend. I beat a heat wave at Oregon’s Deschutes River with a camp chair in the shaded shallows and feet in the water. A perfect setting in which to complete this hauntingly beautiful, gut wrenching yet inspiring book. Macfarlane’s language in places is brilliant prose-poetry. The stories of the rivers and the people dedicating their lives to protecting them are braided tales that somehow gave me hope even if the big picture feels less than hopeful.

Imani Perry has become one of my favourite writers. Her prose is simply exquisite. Its beauty often delivers searing perspectives on US history. Black in Blues is narrative history at its best. Perry tells an entirely different history of perseverance and cultural expression amid and despite the horrors of enslavement, Jim Crow policies and current racism in the US. Like Macfarlane, Perry tells a complex story that is by turns inspiring and enraging. To compel a reader to engage with difficult paradox over the course of a book is high achievement.

Sarah Hall, author

In the current, dismal void of integrous liberal politics, I’ve been reading books about systems change and citizen sovereignty. All Guy Shrubsole’s writing is inspiring, but Who Owns England?: How We Lost Our Green and Pleasant Land and How To Take It Back is really edifying, laying bare our historical and hierarchical social structures, land and wealth inequalities, and what these mean for both ecology and democracy now.

On a similar note, it has always seemed odd to me that so few speculative fictions depict British republics – can’t we even imagine an alternative to the monarchy? Mary Shelley’s The Last Man does so, along with 21st-century hot air balloon taxis and other ingenuities. In the novel, plague exterminates the human race indiscriminately; an avenging female personification of nature. It’s worth remembering there’s more to this radical writer than just the F word.

skip past newsletter promotion

Discover new books and learn more about your favourite authors with our expert reviews, interviews and news stories. Literary delights delivered direct to you

Privacy Notice: Newsletters may contain info about charities, online ads, and content funded by outside parties. For more information see our Privacy Policy. We use Google reCaptcha to protect our website and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

after newsletter promotion

While trying to get a film about wolf reintroduction off the ground, I’ve also been in the zone of lost species. The Hunter by Julia Leigh – an extraordinary novel about the last Tasmanian tiger – is tenser and more tragic than its (albeit brilliant) screen adaptation. The story follows a man tracking this phantom creature for undisclosed, sinister purposes. It takes a cold look at our environmental failures and mercantile choices, and its rendering of the Tasmanian wilderness is spectacularly immersive.

Finally, I loved Raising Hare by Chloe Dalton – the account of a rescued European brown leveret. It’s tender and quietly miraculous. Dalton’s memoir invites the reader beyond personal connections with animals to the common ground where collective campaigning becomes a force that must inhabit the political void.

Helm by Sarah Hall is published by Faber

Dave, Guardian reader

We started The Stand by Stephen King as our first family holiday book club and, at this rate, we will still be reading during the Christmas holidays: spoiler alert, it is a long book.

Having said that, we are all enjoying the ride through an apocalyptic USA. It’s my 14-year-old son’s first King book. Talk about going in at the deep end! It has turned out to be a great book to talk about too. There are so many similarities to Covid that the basis of the story seems very realistic. Of course, it being King, it segues into more fantastical realms, but it works. The cast of characters, in spite of most of the world succumbing to Captain Trips, is pretty big and King does a good job of helping the reader remember who is who.