For refugees, asylees and other immigrants who have sought safety in the United States, government food assistance could go away any day. Health care benefits will soon follow.

After President Donald Trump’s signature legislation passed in July and other policy changes were adopted across his administration, Kansas City-area agencies that work to assist immigrants resettling in the United States are scrambling to understand what they can do to mitigate the damage.

“There is lots of bad news and not a lot of certainty yet on exactly how things are going to be rolled out,” said Hilary Cohen Singer, executive director of Jewish Vocational Service, one of the remaining refugee resettlement agencies in the Kansas City area.

What is certain, said Singer and other immigrant advocates, is that some of the area’s newest — and most vulnerable — residents are going to be left without government help to feed and care for their families.

Since Trump moved back into the White House, he has stopped new refugees coming into the country, delayed and eliminated funding to refugee resettlement agencies and made cracking down on immigration a keystone of his agenda.

The “One Big Beautiful Bill Act,” which Trump signed into law July 4, added new restrictions to what government assistance newly arrived immigrants with the legal right to live here are entitled to.

Undocumented immigrants have always been ineligible for Medicaid, Medicare, subsidized insurance through the Affordable Care Act marketplace and the Supplemental Assistance Nutrition Program (SNAP).

But refugees, people facing persecution at home due to factors such as their race, religion or politics who are vetted and invited to live in the country, have had access. People granted asylum — who arrive in the United States, then receive permission to stay based on similar concerns — have also had access to some government support.

Under the new federal legislation, only lawful permanent residents — people who have green cards — can get those benefits, according to the National Immigration Law Center. In addition, Cuban and Haitian entrants and people here under a compact of free association with Palau, Micronesia and the Marshall Islands can also qualify.

For everyone else, Medicaid coverage and the Children’s Health Insurance Program are expected to end in 2026. Medicare eligibility will end at the beginning of 2027. And SNAP eligibility goes away immediately, although details about how and when that will happen are still unclear.

Taking support services away, said Paul Costigan, Missouri state refugee coordinator for the Missouri Office of Refugee Administration, will mean a much harder road for immigrants trying to build a new life.

“It does take a bit for people to get their kids enrolled in school and for them to get a job and to have stable housing and things like that,” Costigan said. “SNAP and Medicaid have been really crucial in ensuring that self-sufficiency happens sooner. Right now, without that, we’re going to see self sufficiency-happen later, and that’s not what anybody wants.”

Federal funding stopped

Rricha deCant, senior director of policy with the International Refugee Assistance Project, said most states are waiting on guidance from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which oversees SNAP, about how to discontinue coverage.

The United States has always offered refugees health and nutrition benefits and other assistance as they learn the language, get training, find work and learn about their new home.

But that has quickly changed since Trump took office in January. One of his first executive orders stopped refugees from entering the country and discontinued funding refugee resettlement agencies, like JVS and Della Lamb.

Although no new refugees have come into the country since January, those who came in 2024 and at the beginning of this year are still in need of help. Kansas City’s resettlement agencies had to look to the public for help covering rent and utilities for those new arrivals after the federal funding stopped.

“We were astounded at the level of support that came through from the local community,” Singer said. But “at some point, sooner or later, we’re going to experience the limits of that. Local communities cannot replace the federal government as a social safety net.”

Without SNAP benefits, the resettlement agencies will also likely need to turn to the community to help refugees put food on the table. And hunger assistance programs, like Harvesters, are already stretched as federal assistance for their work has also been cut.

DeCant hopes state governments will pick up some of the slack for the lost federal funding.

But states are already seeing major cuts to the funding they get from the federal government for Medicaid and SNAP programs. This summer, Missouri Gov. Mike Kehoe vetoed more than $2 billion in spending that lawmakers had already approved.

Agencies that administer SNAP in Missouri and Kansas did not provide details about how and when benefits would go away or whether the states would offer additional help.

Some federal support to refugee resettlement agencies has resumed, said Ryan Hudnall, executive director of Della Lamb, another resettlement agency, but not all of it.

Della Lamb is planning a community summit Sept. 18 to rally the community to support refugees and immigrants.

Both Della Lamb and JVS had to lay off staff after the January federal funding freeze. And Mission Adelante, another resettlement agency in the area, has said it will no longer serve as a resettlement agency due to declining federal support.

Catholic Charities of Northeast Kansas, Kansas City’s fourth resettlement agency, said in a written statement it would “no longer receive federal funding for resettlement services.”

“While the changes in federal funding represent a major transition, our commitment to serving vulnerable families in need (including Refugee families) remains unwavering,” the statement said. “Catholic Charities of Northeast Kansas will continue assisting Refugee families already settled in our community through programs provided by agency resources.

“Refugee families will maintain access to essential services such as legal aid and citizenship, food, housing, case management, and education, and employment assistance through Catholic Charities of Northeast Kansas.”

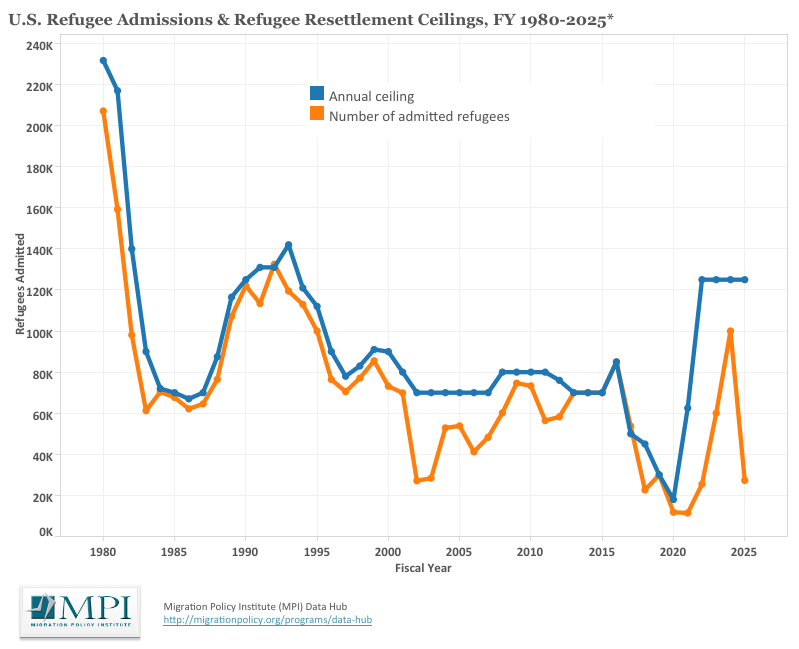

In 2022 under the Biden administration, the United States doubled the number of refugees the country could admit to 125,000, an increase from 62,500 in 2021. The cap remained the same in 2023 and 2024, although actual refugee admissions were lower.

Even the increased cap represented less than 0.4% of the 31.6 million refugees worldwide who have been forced to leave their homes because of war, political upheaval or other disruptions.

It’s unclear when or if the Trump administration will reopen the borders to refugees.

But advocates said refugees already living in Kansas City face mounting obstacles.

On top of the declining benefits available to help refugees get settled, increased immigration enforcement efforts are causing fear and confusion. And although refugees have the legal right to work, some employers are reluctant to hire them.

“Just imagine,” said Hudnall, “it’s a decades-long journey before you’re even comfortable navigating a place where it’s not in your native tongue. You’re learning and upskilling your job skills. You’re thinking about how your kids navigate a different place, a different culture. And now we’re removing some of the safety nets to welcome people.”

Hudnall said it’s becoming increasingly difficult for his organization to reach the immigrants who are already here.

“They’re afraid to engage,” he said.

Chilling effect

Justin Gust, vice president of community engagement with El Centro, said he’s seeing the same chilling effect among the immigrants he works with, even those who have green cards already and shouldn’t be affected by legal changes.

“Trust has been eroded,” Gust said. “People don’t want to put themselves at risk.”

Gust said El Centro is already seeing a significant decline in the number of people applying for SNAP benefits. Usually El Centro helps enroll 2,000 people in the SNAP program annually. But by late summer, it had helped only about 530 people apply.

“At this point, people are afraid,” Gust said.

Earlier this year, the U.S. Department of Agriculture demanded that states provide names, Social Security numbers and other personal information about SNAP recipients. The Kansas Department for Children and Families refused to comply, but Missouri’s Department of Social Services said it would share the information. Federal officials later put their request on hold.

Words have consequences, even when they don’t lead to action, said David Slusky, a professor of economics at the University of Kansas, who studied the effects of the first Trump administration’s “Muslim Ban” on preventive health care for children.

He and researchers from Wayne State University and West Virginia University found that the rhetoric that accompanied that attempted travel ban led to a decline in well-visits and vaccinations among children from families from the Middle East and North Africa.

He and Shooshan Danagouilan, an associate professor of economics from Wayne State who also worked on the study, said they hope their research might inform policies of the current Trump administration.

“When language is bandied about, orders are given and rescinded and then given again that specifically affect minority populations, vulnerable populations,” Danagouilan said, “this language and those orders are not without consequences.”

In the first Trump administration, the rhetoric led directly to families choosing to avoid doctors, even though it meant not maintaining their children’s health. And those individual choices can ultimately affect society as a whole, Slusky said.

“Preventative care is generally the cheapest way to keep people healthy,” he said, “so lack of access to it often results in more expensive health care down the line.”

And cutting off SNAP benefits, Danagouilan said, will have similarly detrimental health consequences. It also sends a terrible message, she said.

“The kinds of policies that are being implemented,” she said, will “announce to the world that in the United States, we have zero tolerance for an immigrant to the point where we will not share our bread with them, which I think is a terrible message to send.”

Related

Type of Story: News

Based on facts, either observed and verified firsthand by the reporter, or reported and verified from knowledgeable sources.