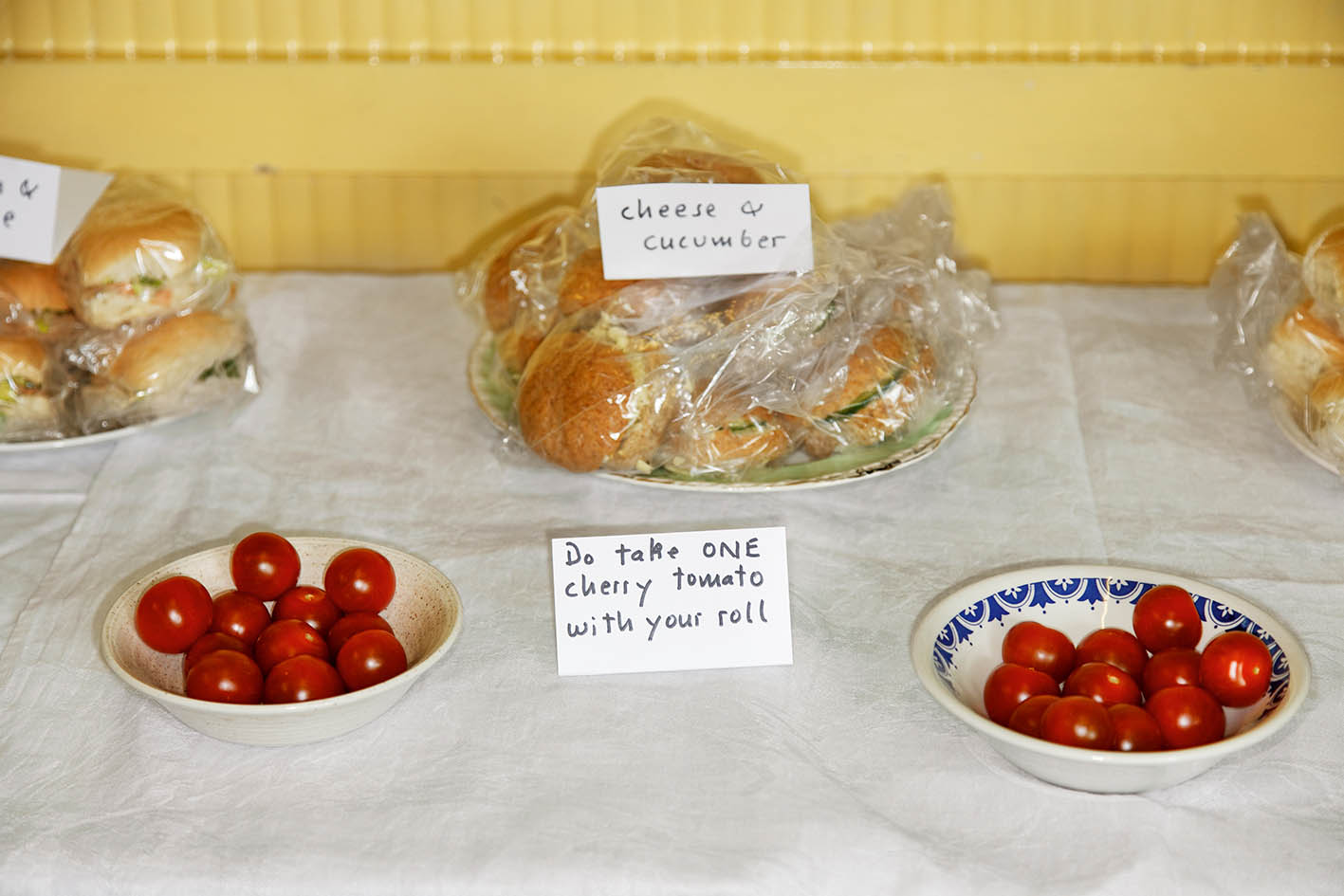

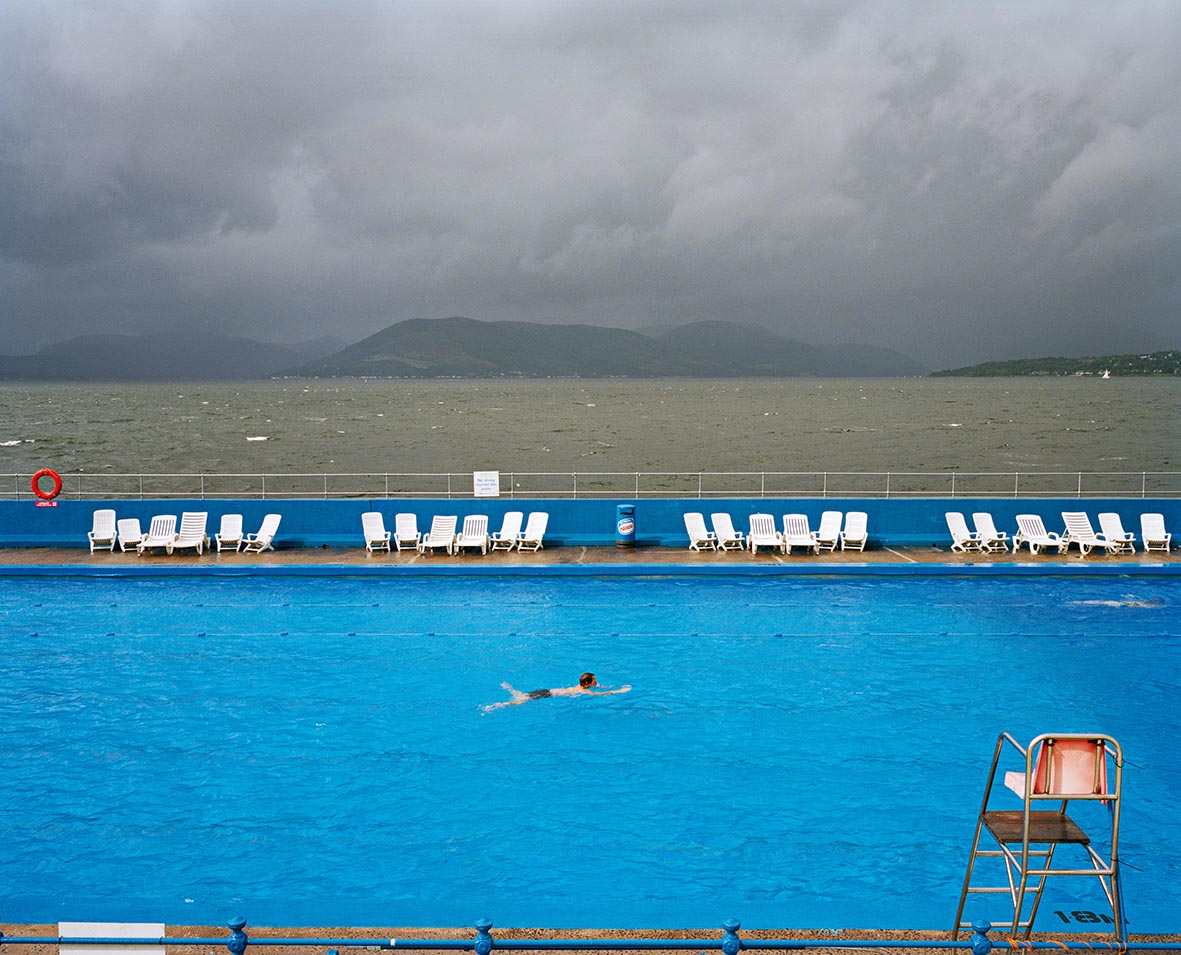

Martin Parr has described his photography as the art of the non-event, an attempt to capture the disappointments of being British: the beach in the driving rain, the lido under a stormy sky, the sign at the fête limiting visitors to only “one tomato” with their cheese roll.

And to some extent England’s most famous photographer feels the same way about interviews — he does not want to talk anything up or debate themes. I suggest that Parr is not much interested in taking celebrity portraits. “Incorrect.” (He’s shot Vivienne Westwood and Mike Leigh, among others.) It must be harder to photograph strangers in public these days? “Not particularly.” Wendy Jones, who wrote the text for Parr’s new memoir, Utterly Lazy and Inattentive, a life in 150 photographs, originally attempted a traditional biography, but called it off after too many questions were met with a brusque: “That’s all I’ve got to say about that.”

Shalfleet church fete, Isle of Wight, 2007. Parr is a regular at country fetes. This one was like stepping back to the 1950s and he admires the sign

© MARTIN PARR/MAGNUM PHOTOS

Which makes him sound like a curmudgeon, when he’s not — Parr is generous, curious, more interested in others than himself. The better word would be contrarian — there is a cussedness born of 50 years of defying expectations, from the teachers who wrote him off at Surbiton County Grammar School (the title of his book comes from a 1966 school report), to the tutors who nearly failed him at Manchester Polytechnic, to the rivals who fought to keep him out of the elite Magnum Photos agency.

A letter circulated to members dismissed Parr’s 1980s pictures of the Liverpool seaside — the ones that made him famous, of kids queuing at the burger bar and young families sharing chips — as “fascistic … kicking the victims of Tory violence”. But in the Nineties Parr got in and later became president. An undying desire to get behind the cordon has got him everywhere — into North Korea, the Freemasons London HQ and out and about with Queen Elizabeth II.

The Queen visiting Drapers’ Hall on their 650th anniversary, London, 2014. The Drapers’ Livery company invited Parr to take photos of their party, which the Queen was a special guest at. Parr has photographed the Queen before but this time he was the only photographer there. He asked the person with her how long it would take her to go around the room. They said 20 minutes and that was exactly how long it took. He got his snap of her leaving, with the camera phones facing her and says she’s the only person who is recognisable from behind.

© MARTIN PARR/MAGNUM PHOTOS

• I am Martin Parr review — a short, sharp portrait of the photographer

Parr, 73, meets me outside Bristol Temple Meads station, an unassuming figure in a lilac shirt and braces, a camera hung around his neck. It is a warm day and he wears Birkenstocks without socks — there is a pair balled neatly on the passenger floor of his car. On the dashboard is Parr’s disabled blue disc — the one perk of being diagnosed with myeloma, a blood cancer, in 2021 is that he can park anywhere.

The downside is that he cannot stand for longer than ten minutes, and mostly walks with the aid of a rollator frame. “But I took 300 pictures yesterday. Of those, I’ll probably use three. If you get six good pictures a year, you’re doing well.” This week he has been on a fashion shoot for Vogue at a local sculpture park. Next week he starts trial medication for the myeloma, a weekly injection that he hopes he can do himself and keep travelling.

The burger bar at the lido, New Brighton, 1983-5. From a series taken over a number of years. Parr likes that no one was looking at the camera and that they are in light clothes

© MARTIN PARR/MAGNUM PHOTOS

Parr’s commercial success has allowed him to open a foundation in Bristol, where he employs 11 people to run a gallery and vast archive of his own and others’ work. In an office lined with books and boxes of old prints (bored couples, rejects; bad weather), he settles down to sort photos from a project into three piles — rejects, maybes and copies to send to the subjects. On the sofa behind him there is a Greggs Christmas onesie and a heart-shaped cushion with a Parr “autoportrait” on it — the photographer unsmiling and looking left of the lens.

For Parr this is a perfect image: deadpan, ironic. “It’s funnier if you can’t smile. As soon as you do, it’s unfunny. Public enemy number one of a good photograph is eye contact and smiling.” He points to his reject pile. “I’ve taken these out because somebody is looking at the camera.” Does he always ask people’s permission? “Yes, and sometimes people say no — it’s an occupational hazard. Sometimes they say it’s illegal, which it’s not in a public place. They get very uppity.” His wife, Susie, for one, hates having her photograph taken (“She’ll say, ‘Oh, I don’t like it, I look too fat”).

Gourock lido, Invercylde, 2004. The architect who redesigned King’s Cross station, John McAslan, commissioned Parr to photograph the A8, from Glasgow to Dunoon. This was the view passing Gourock Lido with a grey sky — typical of a Scottish summer. The image has become famous because Blur chose it for the cover of their album, The Ballad of Darren

© MARTIN PARR/MAGNUM PHOTOS

When pressed, Parr will admit that times have changed: he couldn’t take a picture of a naked baby without asking now, as he did in Liverpool in the mid-Eighties. “No one blinked an eye, but you wouldn’t do it now. That baby got in touch a few years ago — he was a student doing a project on the series, and he asked me a few questions, and sadly I never kept his email. I sent his mother a print.”

The surprise of Parr’s new book is the range of his work, from the early family portraits to the more traditional black-and-white reportage of the early Eighties. But he still thinks his later Eighties work, when he started combining daylight with a flash, is his best. “That’s when I discovered colour photography, and became known in Europe. Of course, it was the height of Thatcher, and it was partly politically motivated to be anti-Thatcher.”

• British summer time: exclusive photographs by Martin Parr

His critics — not least at Magnum — thought he was looking down on his working-class subjects. Did they have a point? “I got accepted by Magnum and ever since I’ve been one of their biggest earners. And that whole anti-Parr brigade — well, [the photographer] Philip Jones Griffiths, who was the leader, he’s dead anyway.”

Gucci Cruise, Cannes, 2018. Parr was on a Gucci shoot in Cannes for a look book. As well as the models, they brought along ten or so older women and young men for the pictures. Parr frizzed out the woman’s hair, gave her a pair of Gucci sunglasses and took the shot. He likes that the photo looks messy and says it shows that it’s often only older, wealthy people who can afford Gucci

© MARTIN PARR/MAGNUM PHOTOS

What was his objection? “Oh, condescending, patronising, blah blah. We got on very well before I went to colour — that’s the irony.” Like Bob Dylan going electric? “Exactly.” If Parr resisted the pressure to be more explicitly political, it was probably because everyone else was doing it: a 1993 photograph of coalminers in the shower in Utterly Lazy doesn’t look distinctively his.

Still, Parr began to explore class more widely, turning an equally unforgiving lens on the upper and middle classes. His photograph of the Bath Young Conservatives 1988 “Midsummer Madness” party is a masterclass in irony — an unsparingly lit garden gathering of stiffs who look as far from delirium as you can get. He flew to Moscow for a millionaires’ convention, and snuck into the VIP enclosure at Henley Royal Regatta.

Conservative Midsummer Madness Party, Bath, 1988. Motivated by a dislike of Margaret Thatcher, Parr decided to photograph Conservative party events. He says access was easier back then. This picture was shown at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in the nineties in an exhibition called British photography from the Thatcher years and was on the cover of the catalogue. Parr likes the man having a glass of red wine, the flowers and the woman’s “solid” hair that “doesn’t look like it would blow in the wind in the Midsummer Madness”

© MARTIN PARR/MAGNUM PHOTOS

As well as class, national identity is a running theme. In the book Parr includes a photograph of a St George’s Day parade in West Bromwich, taken soon after the town voted to leave the EU — girls and women in Union Jack face paint, waving flags. Does it land differently in 2025, in the wake of violent protests that borrow the same symbols?

“Yes. I don’t think that march has been maintained, the big one in the Black Country.” (He’s right: the last West Bromwich parade was in 2020.) A Remainer who is also proudly Middle England, Parr is conflicted on the subject of patriotism. “We don’t celebrate a national English Day. Most people don’t even know when it is. St Patrick’s Day is a big deal, but not St George’s. We don’t bother, and maybe that’s a good thing.”

Parr’s own upbringing, the son of a Methodist civil servant and a school teacher, was solidly middle class: has success changed his sense of status? “I’m not going to turn upper class, am I? The middle class is probably my main stomping ground, and it makes it easier to move between all these worlds.” It helps that class in Britain is so visible. “People display what class they’re in through the clothes they wear, how their hair is done — more so probably than in France.”

France comes up several times, and Parr thinks he is more respected there: he has a big show at the Jeu de Paume gallery in Paris next January, titled Global Warning. “Also, they wrote a song about me.” Martin Parr by Vincent Delerm (2008) is a gentle tribute to all things Parresque: an ice cream by the beach, a blue-rinsed grandmother in an empty casino (“Casino désert/ Martin Parr/ Cheveux bleus, grandmère/ Martin Parr”).

He doesn’t care if some of these things have become clichés: he is told all the time by advertisers that he is a reference point on their mood boards, and why not? “It’s no skin off my nose. I usually like clichés and use them as my starting point.” One of his most popular prints is of a cup of tea on a red gingham tablecloth. “Because if you ask me what I appreciate about the UK, a cup of tea would be one of them. You can’t get decent tea anywhere else.”

Martin Parr

FABRIZIO SPUCCHES

• Martin Parr exclusive: unseen black‑and‑white shots from the colour photography pioneer

Smartphones have changed everything, for good and bad. Parr enjoys Instagram, where he has more than 801,000 followers, and says the iPhone 15 is brilliant for low light — but it’s hard to compose a great street scene when everyone in it is looking at their phone. “It’s a loss, but where would we be without them? Probably happier. I still print everything out. We’re the last generation, you and I, who still have prints and negatives in our drawers.”

Soon Parr will embark on a tour of agricultural fairs in the northeast. When he travels, his wife — a writer and researcher — goes with him, swimming while he works — so much so that, in 2011, she published a history of wild swimming. But Parr can’t swim. He’s never wanted to learn? “I can’t be bothered.” Has Susie tried to persuade him? “She’s given up.” They have a daughter, Ellen, who runs a Chinese-inspired restaurant in east London.

Parr includes a photo of her in his book, six weeks old and howling in a bath. “My wife had very bad postnatal depression, but it was still fantastic to see Ellen and be in charge of her. It was tough, the depression. She went on to the tabs and that finally knocked it on the head.” The crying photo is followed by a simpler, calmer shot of Parr holding Ellen on his lap, taken by Susie — “just to show what a beautiful baby she was”.

What drives Parr are not so much new challenges as failures and slights, the desire to prove people wrong. Parr complains about the snobbery of British critics, whom he says rarely review photography shows. And he is still haunted by the biggest disappointment of his career — going home from a march minutes before the statue of Edward Colston was toppled into Bristol harbour. “I was right there, so I’ve never forgiven myself. It was the one time I could have photographed a news story, I was bang in the middle of it.”

Black Lives Matter protest, Bristol, 2020. Parr is “haunted” by this event. He was at the march photographing the banners, got as far as the statue of Edward Colston and thought nothing was happening so he could go home. When he got home, he saw that he’d just missed that statue being pulled down. He wished he’d stayed five minutes longer to see it. It’s a big regret in his career but he took this the next day, when everything looked neat and sanitised

© MARTIN PARR/MAGNUM PHOTOS

We go on a last lap of the foundation, with its cabinets devoted to Parr’s collections of Soviet space dog memorabilia and boring games (“Motorway, the fast-moving board game for all the family”). On the wall near the kitchen is a photograph of Parr backstage with Elton John. That looks like a fun night, I say. “Yes,” Parr agrees, “he used projections of my pictures in his comeback tour.” Then he frowns, remembering. “But he didn’t include me in his photography exhibition at the V&A.”

Utterly Lazy and Inattentive by Martin Parr and Wendy Jones (Penguin £30) is published on Sep 4. To order a copy go to timesbookshop.co.uk. Free UK standard P&P on orders over £25. Special discount available for Times+ members.

I Am Martin Parr is on BBC4 on Sep 1, 9pm