This book won the 2025 Colorado Book Award for Creative Nonfiction.

Best Wishes for the Future

The reparations my grandfather received from the United States government were used to pay for his first year in the nursing home where he spent the last five years of his life. My grandmother received a check for $20,000. She spent it on my grandfather’s rent. He never saw it. He did not know anything about it. He was ten years into Alzheimer’s. He did not know he had, fifty years earlier, been classified as an enemy alien of the United States and incarcerated in a Department of Justice prison under suspicion of being a spy for Japan. The check was a coin placed in my grandfather’s mouth. It came with a letter: a form apology from the White House. It was not addressed to my grandfather. It was not addressed to anyone. It was stamped with the signature of George H. W. Bush. The last sentence read: “You and your family have our best wishes for the future.

UNDERWRITTEN BY

Each week, The Colorado Sun and Colorado Humanities & Center For The Book feature an excerpt from a Colorado book and an interview with the author. Explore the SunLit archives at coloradosun.com/sunlit.

Five years later my grandfather was dead. His funeral was held in a nondescript church in North Carolina. The church was filled with people my grandfather did not know or would not have remembered. There was a small number of Japanese Americans, but they were outnumbered by white people, some of whom were there to support my grandmother, most of whom were on their way into the sanctuary when they caught a glimpse of the photograph, surrounded by flowers, of an Asian man they recognized but did not know, and thought, with fleeting sympathy, He’s dead.

I was not there. I was eighteen, first year in college, upstate New York. My mother called. “You don’t need to go,” she said. I believed her. Or I believed that my grandfather, who had long since lost his mind, was already dead, and that I had made my peace with his being gone, which quickly proved to be untrue.

When I was young, I did not know anything about Japanese American incarceration. I was not, as a young person—or a person, in general—uncommon in this. Not only did I not know anything about Japanese American incarceration, I did not know that my grandfather had been incarcerated, nor that other members of my family were also incarcerated: my great-aunt Joy in Poston; my great-uncle Makio (Roy), great-aunt Tsuruyo (Pearl), and their daughters, Sally and Carole, in Heart Mountain, my great-aunt Setsuko’s family in Manzanar.

I do not remember when I first heard of internment, which was the only word that seemed to exist. I do not remember if I heard it at home, from my parents, at my grandparents’ house, school. I have a vague memory of a small gray box in my ninth-grade US History textbook, stating, in one lackluster paragraph, a wartime, therefore justifiable, injustice. In the white town in Connecticut where I grew up (compositionally synonymous with the white town where my grandfather died), I might have been the only one who could see it. I do not remember if my classmates looked at me. I remember internment had something to do with my grandfather. He might as well have been the whole story.

I was one of only two Asian Americans in my elementary school. The other was my sister, two grades older. Among the names my classmates called me was Mr. Miyagi. 1985, 1986. Never mind that Mr. Miyagi was old, bald, had facial hair and a Japanese accent; he was a new and convenient reference with which white boys could try out their racism as comedy. I knew, from the credits of The Karate Kid, that Mr. Miyagi was played by Noriyuki ‘Pat’ Morita, but I did not know that Morita was American, and that his accent was part of his character. I did not know that when Morita was young he was in an internment camp. It was not until years later that I learned that it was not an internment camp, but a concentration camp; that internment refers to the detention of non-citizens, while incarceration refers to the detention of citizens; that two-thirds of the people who were incarcerated were citizens and that the other third were not citizens because they were not eligible, by law, to become citizens; and that therefore the difference between being incarcerated and being interned was, for those who were not citizens—many of whom had lived in the United States for decades—outside of their control.

“The Afterlife Is Letting Go”

>> READ AN INTERVIEW WITH THE AUTHOR

Where to find it:

SunLit present new excerpts from some of the best Colorado authors that not only spin engaging narratives but also illuminate who we are as a community. Read more.

I did not know that children were incarcerated. When Morita was two, he was diagnosed with spinal TB. He spent the next decade in a body cast in the Weimar Sanatorium, northeast of Sacramento, then in the Shriners Hospital in San Francisco. When his family was incarcerated in Gila River, the FBI picked him up and carried him to camp. He cried the first four days. “I was homesick for the hospital,” he said. “I could feel and sense and hear all the colors and horrors of incarceration. The sadness, the hopelessness.” Many years later, he returned to Gila River. His wife Evelyn remembers him breaking down. He told her that “a day didn’t go by that you didn’t hear about a suicide or a stillborn or somebody dying from an illness they couldn’t treat.”

One night, at his house, Mr. Miyagi gets drunk and tells Daniel (Ralph Macchio) that he had a wife, that she was in a concentration camp, Manzanar, and that she had just given birth. “First American-born Miyagi,” he says, before passing out. He is holding a piece of paper. Daniel removes it from his hand. A telegram. He reads it: “We regret to inform you that on November 2, 1944 at the Manzanar Relocation Center, your wife and newborn son died due to complications arising from childbirth.” Miyagi received the telegram in Europe. He was in the 442nd, the segregated, all-Nisei combat unit. That scene in Karate Kid seemed to indicate where the Japanese Americans had gone, and where, as represented by Mr. Miyagi, they were forced to keep going. The formula seemed to be that for a citizen to be born, an immigrant had to be struck down; and the citizen dies anyway. Because I was introduced to these things by a movie, and because the movie was not really about any of these things, Japanese American incarceration was introduced to me as fiction. It was my least favorite scene in The Karate Kid. Too dark, too slow, motivated by too much history. It brought the world into the room.

Then it was my grandmother and me. June Shimoda, born Chizuko Yamashita. Her parents were from Fukuoka, both named Yamashita (no relation), and both contract laborers—he as a railroad worker, she as his wife, a picture bride.

My grandmother was not incarcerated. She was born and, except for two years in Fukuoka, raised on a farm in Utah, outside the exclusion zone. The fact that she was not incarcerated and my grandfather was, underscored, in my mind, a difference between them. There were Japanese Americans who were free and Japanese Americans who were not, but I did not know what constituted the difference—gender? generation? citizenship? suspicion? None of these interpretations included racism—that is, none included white people—as if incarceration was a matter of immaculate misfortune.

I interviewed my grandmother in 1999. I was in undergraduate school, taking a class, my first, on Asian American history. The stories she told me became the genesis of my book, The Grave on the Wall. We sat in the living room where I saw my grandfather for the last time and stared out the sliding glass doors into the trees. My grandmother told me about picnics with other families from Fukuoka. I heard the sound of parents gossiping in Japanese. I did not hear, in their gossip, the distance between the Issei and Nisei, nor did I hear gossip as commiseration. I did not see the Issei disappearing through the gossip into Fukuoka, nor the Nisei disappearing into a country that was just as foreign. Instead I felt the pangs of sadness about having missed out on what I perceived as the halcyon days of Japanese America. About having missed out on not only what it meant to be Japanese American, but a contributor to its meaning. I felt seedless and pale, the diminishment of being Japanese in favor of being American. That I, a biracial yonsei, represented, in the form of the future looking back, its mourner and nullification, both the destiny and attenuation of Japanese America.

82,219 Japanese Americans received reparations in the form of $20,000, to account, as a formality, for what they had lost. Or, because loss is a euphemism for theft, what had been stolen. The Office of Redress Administration, created by the Civil Liberties Act—the culmination of a multigenerational struggle, which included the testimonies of over 500 survivors, many of whom were confronting, articulating, and sharing their experiences for the first time—paid out 1.6 billion dollars. The first nine checks were presented to nine of the oldest prisoners in a ceremony in DC, October 9, 1990. Checks 10 through 82,219, accompanied by letters without names or salutations, were delivered from 1991 to 1993.

🎧 Listen here!

Go deeper into this story in this episode of The Daily Sun-Up podcast.

Subscribe: Apple | Spotify | RSS

Mamoru Eto, a 107-year-old Issei living in the Keiro Nursing Home in Los Angeles (where my great-grandmother, Asano Yamashita, also lived, and died), was the first to receive a check. Eto immigrated to the United States in 1919 (the same year as my grandfather). He and his wife Kura settled in Pasadena, where they had ten children. Eto worked on a farm and preached during the winter, to migrant laborers mostly, farm to farm. He opened the First Japanese Nazarene Church in his living room. He and seven of his children—three had already left California; Kura had returned, alone, to Japan—were incarcerated in Tulare and Gila River. Even though he was not, at the time, eligible for US citizenship, Eto forswore his allegiance to Japan. “We’re not Japanese anymore,” he said. “We’re American,” adding: “There’s no other way.”

“Do you know what your family members did with the reparations?” I asked the descendants. “They bought a new roof,” they answered. “They built a front porch. They fixed the patio. Repaved the driveway. Installed a new drainage system. A trash compactor. Hardwood floors. Floor-length curtains. They bought folding screens. A leather recliner. A camera lens. Golf club membership. Fishing equipment. Farm equipment. Groceries. They paid bills. Ambulance bills. Hospital bills. Car loans. Mortgages. They paid for a down payment on a house. Private school. College funds. A film degree. A music therapy degree. Weddings. Long-term care insurance. Assisted living. They bought stocks. Savings bonds. They gave it to their children. Their siblings. Grandchildren. They drank it away. Gambled it away. They went to Japan. Four trips to Japan. (Their first time back.) (Their first time visiting.) To Hiroshima. To China. To Singapore. To Egypt. To Norway. To Peru. To Brazil. To Portugal. On a religious pilgrimage to Fátima. To Spain. To France. On a religious pilgrimage to Lourdes. To Canada. To Mexico. To Hawaii. To Alaska. They started a teriyaki sauce business. An auto repair business. They bought a log cabin. A customized van. A red truck. A Honda Civic. A Nissan Maxima. A Mazda 626. An Acura. A Lexus ES 350. A Toyota Camry. A Toyota Corolla. They donated it to the local community center. The local library (for a collection of books about incarceration). The Red Cross. The Christian church. The Buddhist Church. The Buddhist Churches of America. The JACL. JANM. They split it. They did not want it. They never spent it. They gave it away.”

“The United States is not at war. The United States is war,” writes Sora Han, professor of criminology and law. “Necessity has no law,” wrote Gratian, 4th century Roman Emperor. Gratian makes an appearance in Giorgio Agamben’s State of Exception, in which “state of exception” is elucidated not as a temporary suspension of law but a permanent paradigm of government. Historian Clinton Rossiter explains this paradigm as “crisis government,” ruled by “constitutional dictatorship.” He calls Japanese American incarceration an “assertion of dictatorial power.” Agamben calls it a “spectacular violation of civil rights,” and quotes the eighth of Walter Benjamin’s Theses on the Philosophy of History, that “the tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the state of emergency in which we live is not the exception but the rule.”

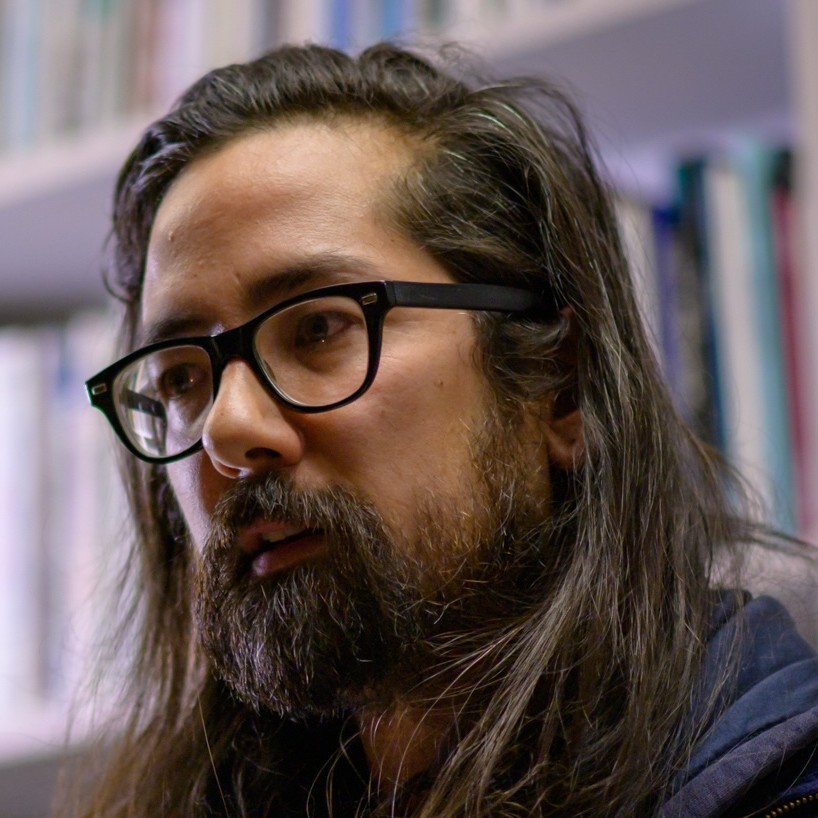

Brandon Shimoda is the author of several books of poetry and prose, most recently “The Afterlife Is Letting Go” (City Lights, 2024) and “Hydra Medusa” (Nightboat Books, 2023). With Brynn Saito, he co-edited “The Gate of Memory: Poems by Descendants of Nikkei Wartime Incarceration” (Haymarket Books, 2025). He teaches creative writing and Asian American literature at Colorado College in Colorado Springs, where he lives with his partner, the poet Dot Devota, and their daughter Yumi Taguchi.