It is hard for anyone to deny the positive effect that the transition from film to digital has had on photography. The sheer number of photographs taken each year has increased exponentially in the digital age, particularly now that cameras are included on nearly every cell phone. But we have lost one aspect of photography: the photo album.

The advantages of digital capture over film are too numerous to list. They range from the ability to preview the captured image in real time, versus waiting days for film and prints to be developed, to the fact that an entire archive of digital family photos can now be held in the palm of your hand, as opposed to filling bookshelves with bulky photo albums.

Despite all of the areas of photography where digital imaging has improved the photographic experience, there is still one area that needs improvement, and it is in the way that digital photos must be viewed. From the very first digital photograph captured in December 1975, digital photos have been displayed on screens designed primarily to accommodate video content.

The majority of today’s digital displays come in one of two aspect ratios: 4:3 full screen or 16:9 widescreen. Not surprisingly, the labels “full screen” and “widescreen” refer to the two video broadcast standards for which they were originally designed. Since video content is historically captured only in the horizontal/landscape orientation, the asymmetrical, rectangular shape was the only logical choice for video.

Unfortunately, when used to display vertical/portrait-oriented still photos, the images must be downsized to nearly half the size of their horizontal counterparts to fit on either of these screen formats. This is particularly annoying when viewing a slideshow presentation that contains a variety of differently composed photos.

The exclusive use of rectangular-shaped displays since the very first digital photograph was taken has delayed the development of a tablet-style, portable digital photo album for nearly 50 years. I could understand the reluctance to change if the problem did not have such a simple yet straightforward solution.

We know that when the television broadcast standard was changed to digital and the display format changed to widescreen, the industry had no problem adding 25% to the width of the existing 4:3 format screens to achieve the new 16:9 screen format. To meet the needs of the photographic community, they could just as well add 25% to the height of the 4:3 displays to create a square display, to be used primarily for displaying photos. The additional headroom would allow individual photos to fit on-screen in the same size regardless of their orientation. Not only would squaring up the screen allow for slideshows of individual, same-sized portrait and landscape photos, but, being symmetrical, the square screen can also be divided equally into grids of 4, 9, 16, 36, or 144 same-sized images per page for a choice of photo album style viewing options.

If the industry is too timid to make the leap directly into creating a digital photo album, perhaps it could start by offering a square digital photo frame to test the waters. I’m sure that sales of a digital frame that provided a better slideshow experience than is achievable on any other existing device would be a welcome addition, if not an eventual replacement, for their existing line of frames. Once the concept proves itself popular with consumers, the long-awaited digital photo album is sure to follow.

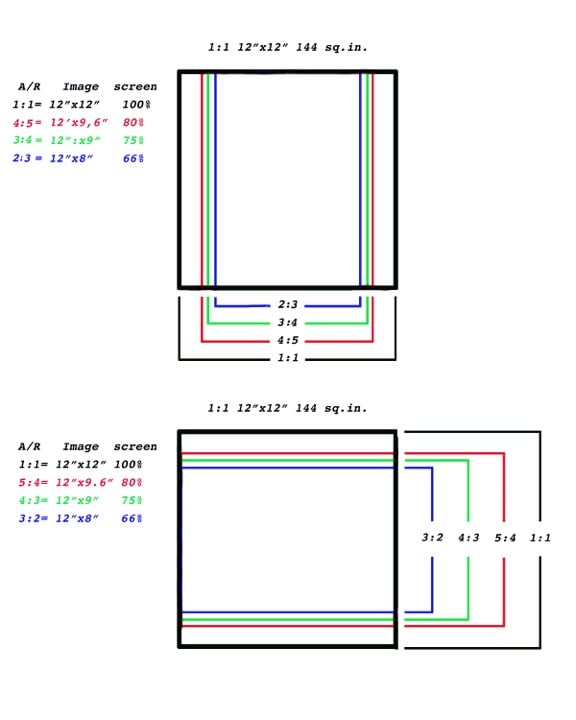

Below are two illustrations. The first depicts how four common aspect ratio images would fit on a square display screen in either direction. I chose to use a 12×12-inch screen in my example, but it can be scaled up or down as long as all sides remain equal.

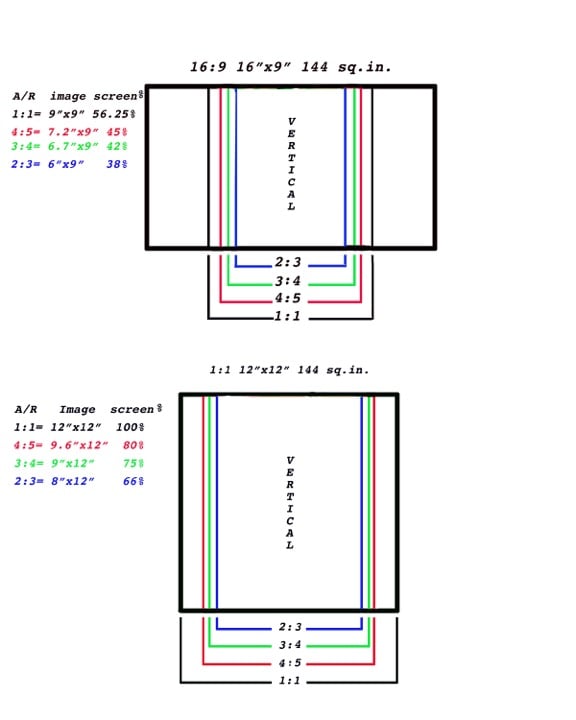

The second illustration depicts how misoriented photos must be downsized to fit on-screen. I used a 16×9-inch screen, which has the same surface area as the 12×12-inch screen, 144 square inches. Compare the amount of screen surface that each photo aspect ratio occupies on both screens, and the difference in image sizes on the two screens, and the problem should be apparent. It should also be noted that the size disparity between images is no better if a 4:3 ratio display is used instead. The closest proportional 4:3 screen is a 12×9-inch screen, and though smaller and not as wasteful of screen surface, because it has the same nine-inch height, the photo size is exactly the same as on the wider screen.

There should be no doubt that, if viewing still photographs electronically is the primary purpose of a device, the best screen format is a 1:1 square.

The opinions expressed above are solely those of the author.

Image credits: Header photo licensed via Depositphotos.