HANS-WALTER MÜLLER’S INFLATABLE ARCHITECTURE BECOMES HIS HOME

Hans-Walter Müller, a German-born architect, artist, and engineer has lived in an inflatable house for over 50 years, where a constantly humming motor keeps the air-formed structure upright. Since the 1960s, Müller has explored the spatial and sensory possibilities of air-supported architecture, building transparent plastic igloos and experimenting with forms that shift and float. His unusual approach is revisited at the Luftmuseum in Amberg through the exhibition Monsieur Luftarchitektur, on view until September 14, 2025. As the first solo exhibition and retrospective of the visionary air architect in Germany, it offers a unique insight into his work shaped by impermanence and imagination.

Pneumatic architecture — a field that trades mass for volume and weight for lightness — offers a provocative alternative to conventional building practices. Adaptable, mobile, and expressive, it continues to challenge assumptions about materiality and permanence. Tracing Müller’s journey and placing his work within a broader history of inflatable design, from its beginnings to its contemporary resurgence, we explore how air-filled visions shape the past, present, and possible futures.

Hans-Walter Müller in his transparent balloon during a ride through the city centre of Paris on World Environment Day, 2001 | image © Marie-France Vesperini

INFLATABLE DESIGN AS A PERSONAL MANIFESTO

Born in 1935 in Worms, Germany, Hans-Walter Müller studied architecture and engineering in Darmstadt before continuing at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. From early on, he challenged the conventions of static architecture, imagining structures defined not by weight and rigidity but by air, movement, and impermanence. Over the decades, his single-walled air-supported structures have taken shape as theaters, exhibition spaces, mobile studios, temporary shopping venues, and shelters in humanitarian contexts.

Known in Germany as the Architekt der Lüfte — the architect of air — Müller has long described his work as architecture of movement, rejecting static form in favor of dynamism and flux. To construct his structures, Müller uses high-frequency welding machines to join cut plastic patterns into large-scale rooms and interconnected ensembles. The lightweight constructions are made from colored, opaque, or transparent materials and can be relocated with ease. Over the years, he has developed innovative fastening systems and solutions for air exchange and pressure loss at entry points. His domes, roofs, and inflatable rooms are scattered across the globe, creating spatial experiences that are as atmospheric as they are ephemeral.

sound structure with resonance sphere on the grounds of La Ferté-Alais

Müller’s collaborations span art, architecture, and performance. In 1970, he created an airborne stage featuring a set design by Andy Warhol, a year later, he developed an inflatable studio for Jean Dubuffet. He also worked with Frei Otto, known for the tensile roof of the Munich Olympic Stadium, yet his most emblematic project remains his inflatable house he built in 1971 and still inhabits outside Paris. Both manifesto and prototype, it is a shifting structure that challenges assumptions about domestic space.

inside Hans-Walter Müller’s inflatable home | image © Lukas Schaller

THE RISE AND RETURN OF PNEUMATIC ARCHITECTURE IN DESIGN HISTORY

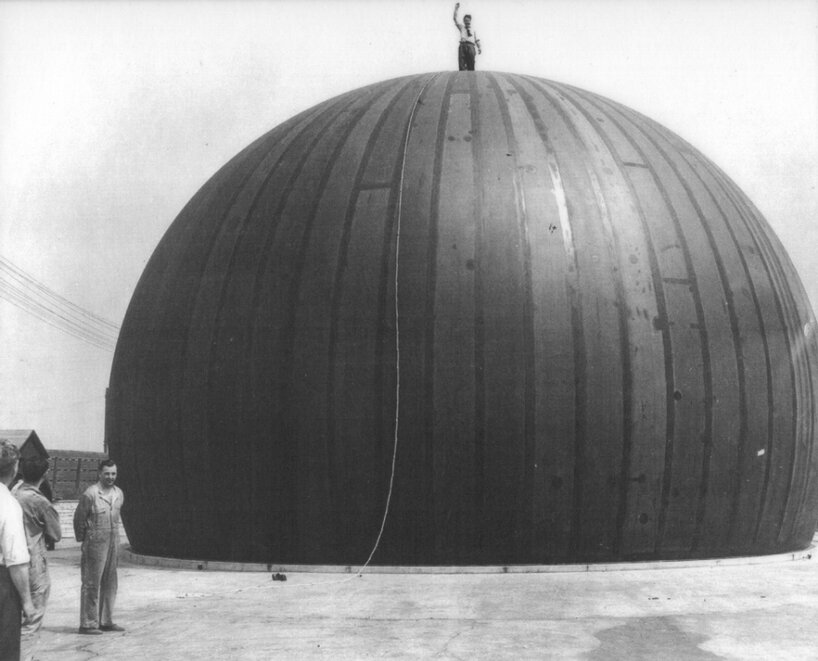

While Hans-Walter Müller played a defining role in popularizing inflatable architecture, he wasn’t alone in reimagining how air and plastic could reshape the built environment. In the mid-20th century, architects such as Frei Otto and Cedric Price were likewise drawn to the possibilities of lightweight, flexible forms. The roots of pneumatic design can be traced back even further, to 1948, when American engineer Walter Bird developed the first inflatable dome to shield military radar systems from weather. These early innovations planted the seed for a new architectural vocabulary — one that favored adaptability over solidity.

Walter Bird standing on top of one of his first pneumatic “radome” prototypes on the Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory grounds in Buffalo, New York, 1948 | image © Birdair, Inc.

This new architectural language gathered momentum in the 1960s and reached a symbolic high point at the 1970 World Expo in Osaka — a landmark event for experimental architecture. Among the most outstanding structures was the Fuji Group Pavilion by Yutaka Murata. With a circular plan and a diameter of 50 meters, it was the largest air-inflated structure in the world at the time. Sixteen identical air-filled arches composed the frame, with a geometric twist. While the central arches followed a semicircular profile, those positioned closer to the ends narrowed at the base, causing their peaks to rise higher. Made of vinyl-coated polyester and held aloft by internal air pressure calibrated at around 1000 millimeters waterhead, the dome appeared to float above the site like a living membrane.

Fuji Group Pavilion by Yutaka Murata, Osaka, 1970 | image © Yutaka Murata, courtesy of Osaka Prefectural Government

Two years later, the Austrian collective Haus-Rucker-Co pushed pneumatic design into the realm of radical art and institutional critique. Created for Documenta 5 in 1972 — the renowned contemporary art exhibition held every five years in Kassel, Germany — Oase No. 7 temporarily transformed the neoclassical facade of the Fridericianum in Kassel. The project consisted of a transparent PVC sphere, eight meters in diameter, mounted on a steel ring structure that cantilevered outward from a window of the museum. Accessed via a walkway piercing the building’s wall, the inflated orb hovered above the entrance like an artificial growth, suspended between interior and exterior. Inside, visitors encountered a surreal micro-environment complete with plastic palm trees, a hammock, and a red flag. Half a century later, the questions posed by such temporary, air-supported structures continue to resonate — especially as architects return to light, mobile, and reversible forms in response to today’s environmental and social urgencies.

‘Oase No. 7, Documenta 5’ 1972 by Haus-Rucker-Co | image © Dennis Conrad

In contemporary practice, pneumatic architecture continues to evolve as a relevant and forward-looking design strategy. For Switzerland’s contribution to Expo 2025 in Osaka, Manuel Herz Architects — in collaboration with researchers from the Kyoto Institute of Technology — have developed a pavilion composed largely of pressurized, air-inflated spheres made from recyclable ETFE. These elements form a lightweight construction of hollow double-shell membranes supported by curved steel beams. Since air pressure is generated only within the outer shell, the structure avoids the need for airlocks at the entrances, maintaining a stable interior climate with minimal technical effort. Echoing the speculative spirit of Expo 70, the design reflects on how impermanent, mobile architecture can meet contemporary demands for climate responsiveness, material efficiency, and spatial adaptability — not as a nostalgic gesture, but as a viable strategy for building more lightly on Earth.