Martha Ronk thinks about Kristen Case’s “Daphne.”

Daphne by Kristen Case. Tupelo Press, 2025. 82 pages.

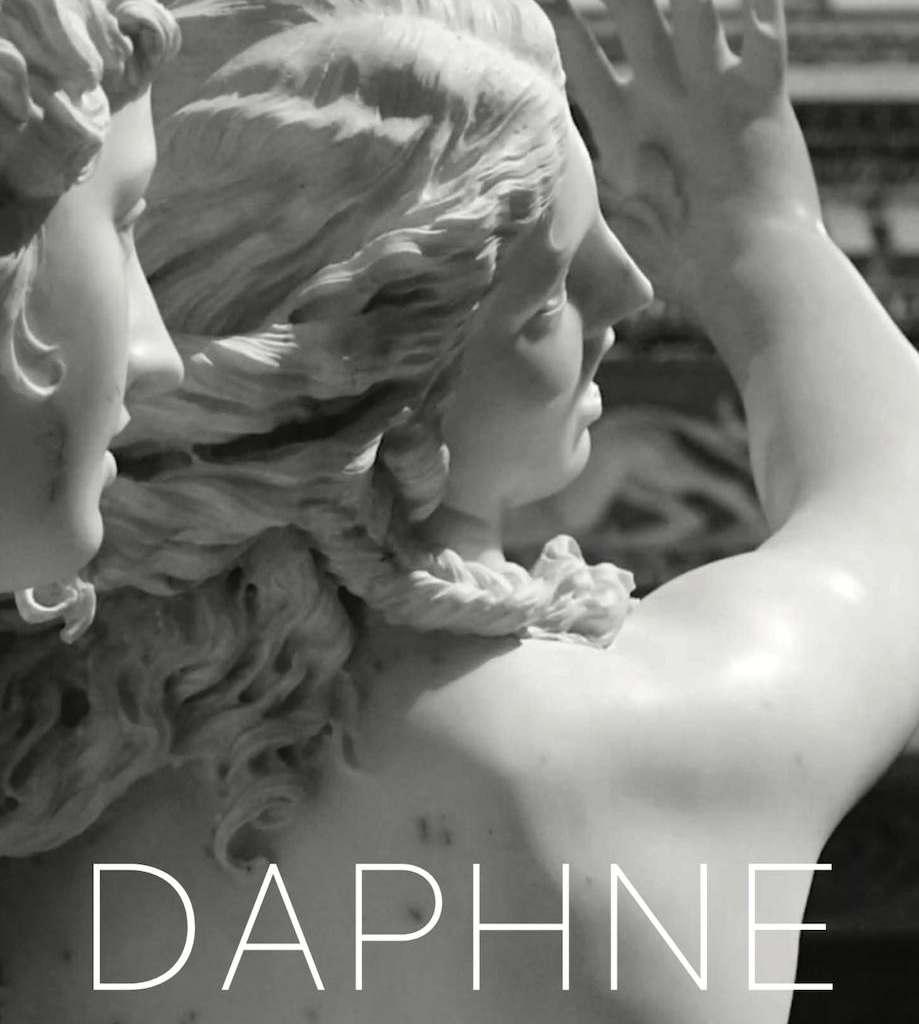

DAPHNE, KRISTEN CASE’S stunning new collection, is a skillful choreography of short prose sections and a few traditional poems, unflinching and expansive in its thinking about violence toward women throughout history and myth. A photo of Bernini’s famous statue in the Galleria Borghese, which depicts Apollo’s pursuit of Daphne, is on the cover, the figures wound around one another, rhyming, as it were. In the book, the speaker appears as both the body of the assaulted and the voice of the poet. As she says later in the book,

Maybe my question is: how can I be a poet? Or maybe it is: how can I be inside both the poems and my own body? Thou eastlit frozen wood, thou shiver of hemlock, thou cloud of

light.

Daphne’s short prose sections—from one to six or so per page—play off one another in complex and interchanging ways. Like her earlier book Little Arias (2015), Daphne explores the uncertain nature of existence by incorporating a vast number of texts, plumbing grief, and closely examining the sensory world. In the first section of Daphne, Case posits two versions of what happens in the myth of Daphne and Apollo: in one paragraph, Daphne’s tree-life is one of freedom and “a shivering and light-saturated language”; in the other, she and Apollo run toward mutual ecstasy. The language of the book is direct, personal, intimate, self-aware, and self-correcting, often including a sentence describing nature as a metaphoric coordinate. The two questions excerpted above seem to acquire a shiver, a bit of hemlock (a poisonous plant associated with death), from the third line. My assumption is that the author means to create a speaker as close to an “I” as possible, although she also questions who that “I” might be. In another line, the speaker says, “You imagine the sky above the lake, broken open,” and follows with “I wonder what I mean by you.” With curiosity rather than avoidance, the lines question the lyric vehicles (speaker and addressee) they utilize.

Everything in the book pulls toward an intimacy with the reader that is rare, affecting, difficult to achieve. At the same time, the book is highly analytical and intellectually challenging. The speaker is complex. She scans lines of poetry; she tells us that she is reading a biography of Wittgenstein, that she has read Hamlet and Keats criticism, that she has built fires in Maine and examined the melt of snow with precision. Yet a line is then inserted like a traumatic event, unsettling and piercing the reader: “Violence is a secret key. Emptiness and the terror that attends it.”

One of the most appealing aspects of Daphne is its focus on thinking. On one spread of just two pages, the speaker says: “I think about Rosmarie Waldrop’s sentence,” “I am reading Wittgenstein’s On Certainty,” “This suggests,” “I imagine,” and “my initial response […] was to wonder why.” For me, a most impressive and intimate quality of the book is its poetic presence and the way it reflects profoundly on how to respond to, how to imagine, and how to think through trauma and its lingering aftermath. Trauma is not a new subject for poetry; in fact, it has been a very common subject of recent American poetry, but there is innovation in the way Case’s research and readings of other authors go hand in hand with personal experience and reflection. Since the organization of the book is paratactic—that is, each short paragraph, surrounded by white space, juxtaposed to another short paragraph—connections seem to multiply. The effect of this is rich and enveloping; readers participate in the speaker’s process and thus rethink their own experiences. The book as a whole is a meditative echo chamber.

In the early pages of the book, the poet addresses both the myth of Daphne and a personal assault in graphic terms:

When I was [ ] a man twice [ ] known [ ] child. He [

] and expertly [ ][ ]

couldn’t move until [ ] weeping cloud.

The description continues in this manner as the child is lifted and handled. She has no idea whether the man knew what she felt; she was asked one question: “fast or slow?” The blanked-out diction amplifies the speechlessness of the encounter. Unable to resist the man’s force, the speaker is made into a thing, made zero. She continues: “I am interested in the relation between my becoming frozen and insensible and Daphne’s becoming arboreal, the way both occur at the moment of being caught. The trauma literature calls this response ‘tonic immobility,’” a kind of “apparent death.” She then asks whether desire destroys love, and what might soothe or offer repair in the aftermath of assault. In addition to how to relate to the mysterious “you,” the poem asks how to be a body, how to be a poet with a specific obsession, how to read Thomas Wyatt or Keats or Hamlet in this context. Analyzing Keats’s “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” the speaker suggests the urn remains “unravished” and therefore an object that fosters imagination.

A central section focuses on Wittgenstein’s On Certainty (1969) and on a biography of Wittgenstein that describes his relationship to Francis Skinner. This material echoes the poet’s relationship to the certainty and uncertainty of her past. While at first Wittgenstein sees nothing wrong with his sexual encounter, he goes on to experience shame, and he finally confesses to his own cruelty. The speaker quotes Skinner—“I am unhappy”—then repeats it in her own voice: “I am unhappy.” Later in this section, the parenthetical (“all resonance grows from consent to emptiness”) again captures her contradictory feelings. We learn that Wittgenstein wanted Skinner dead, and the speaker reflects: “When I feel that another person’s desire for me carries with it the secret wish that I were dead, is this a mistake or a mental disturbance? Whose?”

A subsequent section of the book expands on this idea of emptiness and annihilation, “the garbage feeling” after trauma. We feel the void in observations of nature (darkness, snow), references to other thinkers (“I think of Simone Weil thinking about The Iliad and starving herself. Her Body. Her self”), and the certain uncertainty of her own account: “Of all the things I could tell you, what happened explains the least.” In a section focusing on Hamlet, the poet addresses Ophelia as another emptied woman:

As one incapable of her own distress. Experiment: what would a woman look like emptied of everything, even her own distress? Leaden clouds delimitate a cold pearlescence. Result: dumb echo. Floral concentrate of sex and singing. The stove sounds its invisible expansion behind the amplified nothing of the fire. The wood you carried an hour ago resolves into a fine ash.

Woven through the collection are sections titled “Tonic,” lyric descriptions of nature that serve as balm and counterpoint. Although the tonics function as a form of relief, providing pause and songs of wonder, they don’t conclude anything. Like the space of nature, they remain open, necessarily repetitive. “I long to be with you in any open space,” a line from Skinner to Wittgenstein, becomes a refrain throughout Daphne, a complex relational longing.

Most often, the poet finds solace in nature or in the pathetic fallacy, in which nature reflects human feelings. A weeping cloud invites an extended simile: “Weeping, like shaking, is the body gone into ungatherable being.” There is a wordless repair to light moving through leaves. In “Tonic 3 (Daphne),” she leaves her experience and even her words behind to become rapturously and magically green:

forget the sentences about your body and its capture the words falling from you one by one even as you feel them becoming: green and green and green and green and the way light enters you and

The penultimate section of Daphne, “Six Variations on Beethoven’s Opus 109,” combines considerations of the musical piece with a scene between the speaker and her eventual rapist:

At the dance, you were aware of him watching but thought you were imagining it. […] After the dance, he called you an exhibitionist. Looking through the old camp photos, he said you were the prettiest girl. This felt incorrect because you were very young in the pictures but also exciting to be the prettiest.

This recollection of the early stages of his predation are followed by a more abstract meditation on inertia, a meditation I find myself rereading for its insight and complexity, and for the way in which it asks for a reexamination of the central traumatic event and the idea of “inertia” itself:

Inertia is a tendency to do nothing or remain unchanged. I like the second meaning for its suggestion of a kind of modest integrity. At the bottom of your breath you can feel this place in yourself: the edge of your inertia. This is the place where your being would fold, give way, unbecome.

Ending with “The Invisible Country of Remade Desire,” whose title comes from a phrase Skinner used, Case ultimately distances desire. Perhaps desire is most visibly or safely felt through the intimacy of language itself, one’s own words or the echo of another’s:

I long to be with you in any open space.

LARB Contributor

Martha Ronk has published 13 books of poetry, most recently CLAY bodies + matter (Omnidawn, 2025), and is a retired professor of English literature, formerly at Occidental College. She posts infrequently on Instagram and will read at the American Museum of Ceramic Art on October 26, 2025.

Share

Copy link to articleLARB Staff Recommendations

Rosanna Young Oh reviews Jimin Seo’s “OSSIA.”

Paul Vangelisti considers Susan Thackrey’s “Farther,” Joel Chace’s “Maths,” and Claire DeVoogd’s “Via.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!