Anthony Richardson lasted 10 starts before his first benching, five more before his second.

The No. 4 pick in the 2023 NFL Draft has been the same player he was at Florida: inconsistent and injury-prone with dazzling but infrequent flashes that speak to his talent. Two years ago, the Indianapolis Colts hoped he’d become the face of their future.

“You play 12 or 14 years in this league and you’re an outstanding quarterback, you’re gonna make a billion dollars,” the team’s late owner, Jim Irsay, told Richardson a day after the draft. “A billion.”

It was typical Irsay exaggeration, but the stakes were nonetheless obvious: the Colts were banking on Richardson — a 21-year-old who’d made 13 college starts — being their answer.

He hasn’t been. Last month, Richardson lost his starting job to Daniel Jones, a former first-round pick who washed out with the New York Giants after six seasons. It’s unlikely Jones becomes Indianapolis’ long-term solution, meaning Colts general manager Chris Ballard’s six-year search for Andrew Luck’s successor will continue. That is, if Ballard is still running the team next offseason.

Finding that answer — a franchise quarterback — remains job No. 1 for anyone in charge of an NFL roster. Heading into that 2023 draft, Ballard was essentially staring at an ultimatum handed down by Irsay: take a QB or else. If Richardson hadn’t been available at No. 4, Irsay later admitted, the Colts would have taken Kentucky’s Will Levis, simply because he was the next QB on their board. Levis instead fell to the second round, was benched after 20 starts in Tennessee and lost his job to top pick Cam Ward this spring.

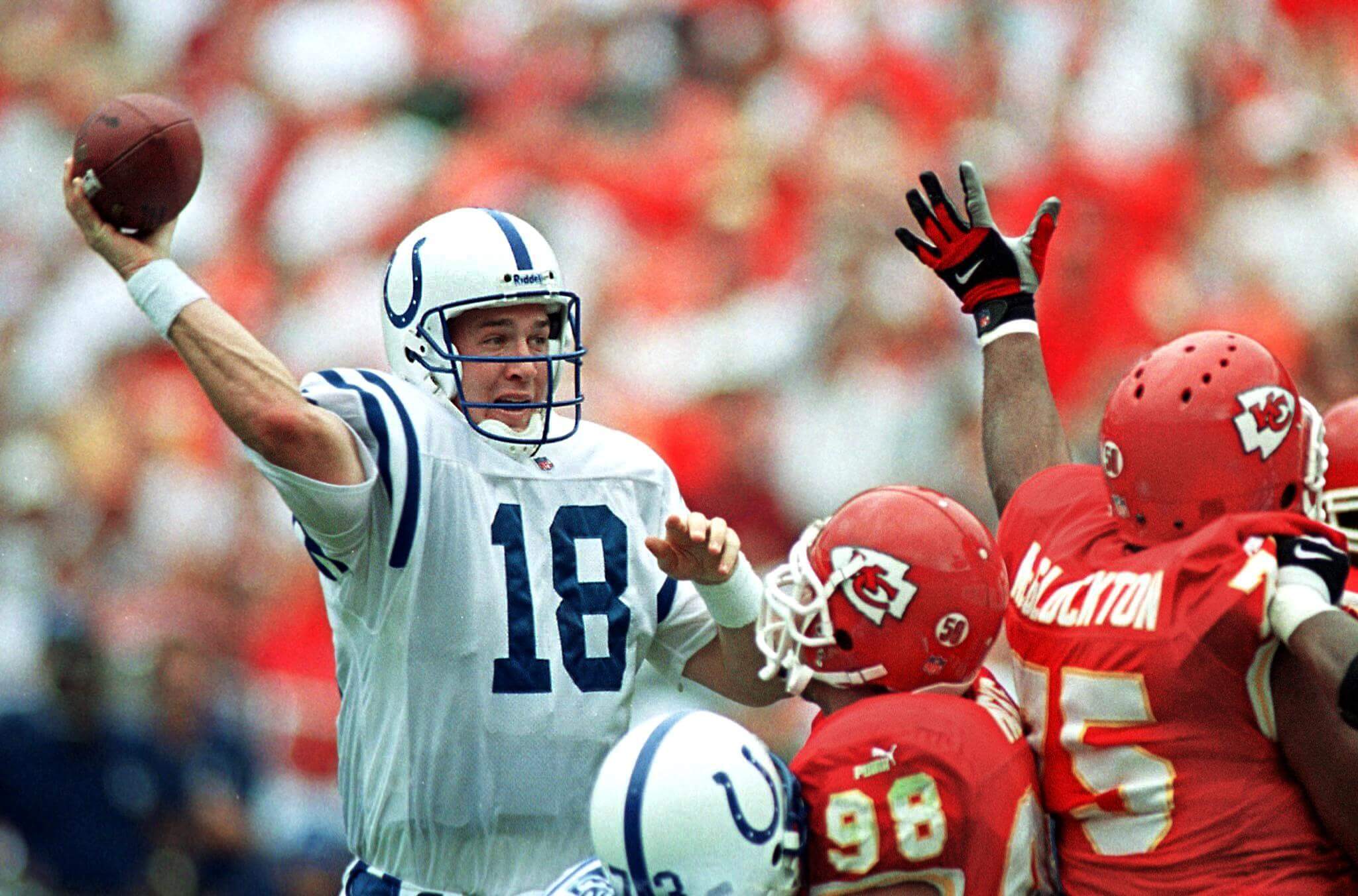

“I think teams get too afraid of passing on a guy they think could be special,” says Hall of Famer Peyton Manning, who spent his first 14 seasons in Indianapolis. “Even if he’s not a fit for them or he’s not ready or if there’s not a great chance it’s going to work out, they’re still gonna draft him high so they can tell their fans, ‘Hey, at least we tried.’”

Ballard has left the door open for Richardson to compete for the starting job next summer, but after two benchings and 17 games missed due to injury, the young quarterback carries a classification that threatens to define his career: a bust.

All of which leaves the Colts in the same spot they’ve been for the last half-decade: desperate for a quarterback.

“Teams would give anything to get the right guy,” says Alex Smith, the 2005 No. 1 pick. “The problem is, some of them don’t have a clue what they’re doing.”

Not that Richardson’s early stumbles are rare. Even the greats wrestled with the burdens of the position and the constant humbling it dishes out.

Seven quarters into his own career, Manning had thrown six interceptions and was nervously sneaking glances at his coach on the sideline, worried he was about to get benched. “You’re dying out there,” he says. Another Hall of Famer, Troy Aikman, remains convinced his days in Dallas would have been numbered had the Cowboys not changed offensive coordinators after his first two seasons.

Seven quarters into his NFL career, Peyton Manning had thrown six interceptions and was actually hoping his coaches would bench him for the rest of the game. (Dave Kaup / AFP via Getty Images)

But that’s the job: In no other American enterprise is the face of an organization routinely a 21- or 22- or 23-year-old fresh out of school, thrust into a new city with new bosses and new colleagues and tasked with flipping their fortunes in a little under two years.

“Take all that, then pour some gasoline on it,” says Andrew Luck, the 2012 top pick. “That’s the day-to-day, moment-to-moment intensity of what it actually feels like.”

And that’s coming from a prospect who entered the league as polished as any. Luck’s rookie season in Indianapolis was ridiculous: he led a two-win Colts team from the year before to 11 victories and a playoff berth while head coach Chuck Pagano spent most of the season in the hospital fighting leukemia. Behind closed doors, Luck says, he could barely keep his head above water.

“Andrew Luck admitting that,” says Vikings coach Kevin O’Connell, “validates everything I’ve ever thought about the quarterback position.”

What’s grown to irritate O’Connell, a failed pro QB himself, is how short-sighted some NFL teams have become. Too many organizations are in a hurry, he believes, to decide if their young quarterback is the answer or not. They abandon their plan — or worse yet, don’t have one to begin with. They move off one player to chase another, intoxicated by hope, the cycle restarting itself all over again.

“In what world do you go from wearing a life vest and learning how to swim to being thrown in the deep end in the middle of a 200-meter freestyle against Michael Phelps?” O’Connell asks. “We decide in this league very quickly whether a guy can or can’t play quarterback like it’s a simple yes or no: This is the guy or this isn’t the guy; let’s either have a parade in the streets or let’s move on and try and find another one.”

It was those frustrations that led O’Connell, in the midst of a season in which he’d be named the NFL’s Coach of the Year, to offer a biting assessment last fall on “The Rich Eisen Show”: “I believe organizations fail young quarterbacks before young quarterbacks fail organizations.”

In the QB world, O’Connell’s words struck a nerve.

“I don’t think I’ve ever heard it put so well,” says Smith, now an analyst at ESPN after his 16-year career ended in 2021. “Certainly not from an active head coach.”

“He’s dead on,” adds Bruce Arians, a two-time Coach of the Year and a Super Bowl winner with the Buccaneers in 2020. “No one gives these kids a chance to develop anymore.”

Aikman, a three-time Super Bowl champ now of ESPN’s “Monday Night Football,” also agrees: “If you have to say who fails who the most, it’s the team failing the quarterback.”

The thought begs an obvious question: If O’Connell’s right, why do so many teams keep screwing this up?

‘It’s easier to find one when you’ve got one’

That’s something Ballard would mention to Irsay during the Colts’ years-long odyssey to find Luck’s replacement in Indianapolis.

The GM cites two recent examples: the Chiefs landing Patrick Mahomes in 2017 and the Ravens getting Lamar Jackson a year later. Both teams had entrenched starters in place — Smith made three Pro Bowls after being traded to Kansas City in 2013, while Joe Flacco’s Baltimore career included six playoff appearances and a Super Bowl MVP award — making it far easier to stash a first-round quarterback on the bench.

“If you’re gonna draft a guy and sit him, everybody in the building has to buy in,” Ballard says. “You gotta withstand the fans clamoring for him to play, and that’s a whole lot easier when you’ve got Alex Smith and you’re winning or Joe Flacco and you’re winning.”

Conversely, when a team needs a quarterback, like the Colts have for years, the pressure heightens. Evaluations are muddied. The process is tilted. It’s why so many organizations reach in the draft, year after year.

“Teams force it, simple as that,” says Matt Hasselbeck, a 17-year veteran who retired in 2016. “I promise you, some of these owners are just like, ‘Man, we need a quarterback who can sell some jerseys.’ They just want someone who’ll make them relevant.”

That’s typically where it starts, with a team in flux — an impetuous owner with too much say or a coach or GM on the hot seat — drafting a quarterback as a cure-all when only a few actually are. From there, the chaos intensifies because the need to win is more immediate. The QB never gets a fair shot.

“I hate it,” Manning says. “Teams draft these guys without a plan. They all say they have one, then the kid ends up playing for three coordinators his first two seasons … It’s like a young couple thinking about bringing a baby into the world. If you’re not sure you’re ready, just don’t do it.”

Take the last two drafts, Manning says. Chicago’s Caleb Williams and Carolina’s Bryce Young, the No. 1 picks in 2024 and 2023, respectively, enter this season on their second head coach — third if you count interims — and third play caller. So far, all they know in the NFL is turnover.

“I just wish a team would admit, ‘OK, we need a quarterback this year, but we’re not 100 percent sure our coach is the right guy, so we’re not gonna bring him into this,’” Manning continues. “Of course, they always draft the quarterback.

“Those teams were not ready,” he says of the Bears and Panthers. “That’s just how I feel.”

The NFL’s QB development problem?

QBTeamDraftPickBenchingAge

Jets

2021

2

30 starts in

25

49ers

2021

3

4 starts in

24

Patriots

2021

15

41 starts in

26

Steelers

2022

20

24 starts in

26

Panthers

2023

1

18 starts in

23

Colts

2023

4

10 starts in

22

Titans

2023

33

20 starts in

25

Hasselbeck cites a disconnect in the scouting phase, when the two sides of an NFL building — personnel and coaching — clash on what they value most in a prospect. Scouts, he says, typically seek elite physical attributes that are unteachable, banking on the coaching staff to figure out the rest. Coaches tend to covet more polished players who’ll arrive with a higher floor and need less time acclimating to the pro game.

“Think of it as builders and realtors,” Hasselbeck says. “They’re in the same business, but they don’t always get along and they don’t always value each other’s opinions.”

He shares a scene from the NFL Scouting Combine a few years back. Two groups were watching the same QB prospects run through the same drills and coming away with completely different evaluations. “So the scouts are all excited. They’re asking each other, ‘Did you see that throw?’” Hasselbeck says. “And the coaches are like, ‘He’s holding onto it too long. That’s a sack. Interception. Sack.’”

Several current and former quarterbacks pointed to a scouting process that prioritizes the wrong things. The ability to “make any throw from any platform” — common scouting lingo — belies the fact that the so-called intangibles are what ultimately determine success. Luck says he wouldn’t draft a quarterback without elite processing capacity — and humility. “Can you make a mistake and not repeat it? And more importantly, can you own up to it?” he says. “Because that’s the job.”

The highlight-reel, 65-yard pro day throws against no defense that light up social media? Ignore those, according to QBs and coaches. That’s not what wins on Sundays.

“Accuracy over arm strength for me,” Arians says. “And are they coachable? If they do the regular stuff we design, I’m happy. But for some reason these kids are used to being Superman in college and refuse to throw it away. That’s where it gets sideways.”

Texans starter C.J. Stroud, the 2023 Offensive Rookie of the Year, says he’d never draft a quarterback “without talking to all of his (college) teammates first.”

And Bill Parcells, the Hall of Famer who coached four NFL teams, once put it this way: “You wanna know if you’ve got the right guy at quarterback? Don’t watch him after he throws three touchdowns and wins you the game. Watch him after he throws three interceptions and loses it.”

For Matt Ryan, a former MVP, 15-year pro and current analyst for CBS Sports’ “The NFL Today,” the tenets of the job were simple: preparation, consistency.

“Really good quarterback play is oftentimes making the boring sexy,” he says. “It’s not how far you can throw it. It’s making the right decision in critical situations over and over and over. Look for the guys who can do that.”

‘Coaches say they’re going to build their offense around what the quarterback does well. Only a few actually do it.’

That’s Aikman’s argument, that too many coaches are too rigid in their approach, refusing to shape their system around their QB’s skill set. It’s not simply about finding the right quarterback in the draft; it’s about building an infrastructure that will allow that quarterback to grow into the job after he arrives.

The reality, Smith pointed out, is that only a handful of teams get this right. “Maybe seven or eight,” he says. “Ten at the most?”

As for who to blame, Aikman starts at the top. Bad owners hire stubborn coaches, sabotaging young quarterbacks from the beginning.

“A lot of times these owners don’t even know what they should be looking for in a coach,” he says. “And if you don’t have the right head coach and the right offensive coordinator, you’re not giving the quarterback a real chance.”

Aikman speaks from experience: twice during his 12-year run in Dallas he played in what he calls “a high school passing attack.” It irritates him to this day.

Smith arrived in San Francisco in 2005 having thrived in Urban Meyer’s spread option attack at Utah, piling up 15 rushing touchdowns in his last two seasons there. Then he joined the 49ers and was told he couldn’t run the football. In college, Smith lived in the shotgun; his rookie year in San Francisco, he was ordered to take every snap under center. “I had to ask the coaches’ permission to get in shotgun on 3rd down!” he says. “How insane is that?”

It took until the middle of his second season — and the arrival of an aggressive OC in Norv Turner, the same coach who saved Aikman’s career — for Smith to get comfortable. Then, 10 games in, Turner called him into his office and told him the offense was changing. Again. “I don’t agree with this,” Turner told him, “but the head coach told me we need to shorten the game and take some pressure off the defense.” The 49ers were going back to being a run-first team. Smith was crushed.

“Every possession was run, run, pass,” he says. “Do you know how hard it is in the NFL to throw it on third down when the defense knows you’re throwing it?”

Finally, seven years into Smith’s NFL career, Jim Harbaugh took over and gave him the green light. “Why don’t you ever run it?” Harbaugh asked. “You were great at it in college.”

“Because I’ve never been allowed to,” Smith told him.

After thriving in the shotgun in college, Alex Smith was forced to play under center for much of his early NFL career. “For so long, I was totally lost,” he says now. (Robert B. Stanton/ Getty Images)

Smith points to Andy Reid, whom he started under for five years in Kansas City, as the best in the league at tailoring his system to his QB’s strengths. The Chiefs’ offense he ran, for example, is completely different than the one Mahomes pilots now.

“Andy doesn’t just know a playbook,” Smith says. “When a coach just knows a playbook, he spends his whole career looking for players who fit that playbook. And when they don’t fit, it’s never going to work because the coach can’t adapt.”

After a promising rookie season in New England in 2021, Mac Jones regressed considerably a year later. Why? Start with the Patriots’ hubris: that season, Jones was shuffling between two play callers — Matt Patricia, the team’s former defensive coordinator, and Joe Judge, the team’s former special teams coordinator — neither of whom had any business running an offense. That, and the line was a mess. The receiving talent was nonexistent. Jones was set up to fail.

Arians took issue with the criticisms of Young in Carolina a year later. “Everyone’s all over this kid because he’s struggling. Well, he’s a rookie. He’s supposed to struggle. And nobody mentions that he had better receivers when he was at Alabama.”

Team culture matters, too. Hasselbeck was further along in his career when he signed with the Titans in 2011 to take over for Vince Young, a former No. 3 overall pick who flamed out after five seasons. “I’ll never forget what the media relations director told me the first day I was there,” Hasselbeck says. “He’s like, ‘Hey, thanks for showing up on time today.’ I was like, ‘When else would I get here? I’m the starting quarterback.’ But it sort of shows you what they’d experienced before.”

Early on, Hasselbeck remembers wanting to throw after practice and being startled at how unnecessarily difficult the task was.

“I had to go to the equipment room, which was locked, and bang on the cage for 10 minutes,” he says. “They only have three guys working — and they’re working their tails off — and I ask, ‘Is it OK if I borrow a football to go throw?’ And they’re like, ‘Yeah, hold on, it’ll be a few minutes. Make sure you bring it back.’”

Two years later, Hasselbeck landed in Indianapolis as Luck’s backup. His first week there, Luck summoned his receivers for some post-practice throwing. “Within minutes,” Hasselbeck says, “the entire building knew.” A bag of footballs sat waiting for them on the field. Equipment managers stood in position. The video team was ready to record. Trainers had water bottles filled.

“The wake Peyton left,” Hasselbeck calls it. “There’s a standard in every building, whether it’s function or dysfunction,” he says. “And usually you can tell right away.”

Luck had the seismic task of replacing Manning in 2012. Looking back, he explains, there were two sides to it. One was the pressure. “Having to fill Peyton’s shoes, that never bothered me,” he says. The other was the infrastructure already in place: The Colts’ building was set up for a quarterback to have success. For 14 years, Manning made certain of it.

“That was huge for me early on,” Luck says.

‘Every week is like taking all five of your final exams in college at once’

Rich Gannon, a former league MVP, relayed that warning to Ryan before his rookie year with the Falcons in 2008. It’s part of the reason so many quarterbacks struggle early on: the workload is absurd.

“A gauntlet,” Ryan calls it. “The four hours a day you spend on football in school are not the 14 or 15 you spend on it in the NFL. There’s a repetitiveness that can just grind you down.”

Plus, as Ryan points out, “there are no Ball States on your schedule.”

That’s where the team must step in, O’Connell says. It’s on the GM to ensure there’s a veteran quarterback on the roster. It’s on the veteran quarterback to show the rookie what each workday should look like. It’s on the position coach to teach him how to diagnose film. It’s on the coordinator to make sure he’s not overwhelmed in training camp.

Then, O’Connell says, comes the most essential part: coaching them through failure.

“I’ve thought a lot about this,” he says. “And I’ve realized the most important part of a quarterback’s development is when it doesn’t go right. When there are growing pains, when there are struggles, that’s when you have to buckle up and put on your big-boy pants as a coach. You have to have a clear-cut plan on how you’re going to improve: what film to watch, what drills to do, how to measure progress, even if it’s really small.

“It’s our job as coaches to look inward first and exhaust every resource possible to get these guys to play like the best versions of themselves.”

Smith didn’t get that in San Francisco, and his nightmare dragged on for years, through four head coaches and seven offensive coordinators. He went from running between 20 and 25 concepts out of three formations at Utah to a 49ers playbook that had 115 different play calls on it each week. Then his playbook changed, and changed, and changed, every offseason for seven years.

“It’s like trying to learn Spanish, then Portuguese, then French, then Japanese,” he says.

His confidence vanished. He came to dread home games, knowing the boos were coming. He’d find himself watching film alone. In private, he started to wonder how long it would take the organization to realize it had made a massive mistake.

“I didn’t even know what an NFL quarterback was supposed to look like,” he says. “I had no idea what the preparation was supposed to look like from Monday to Sunday. For so long, I was totally lost.”

One way to counter that, most believe, is to put players around the quarterback who will play active roles in their development. “The QB room matters a ton,” Hasselbeck says. “Like in Green Bay, I was the first backup to Brett Favre who was younger than him, and that was eight years into his career. Before me they just surrounded him with older guys they thought would be future coaches. That wasn’t an accident.”

Neither is Williams’ new teammate in Chicago. Case Keenum is an 11-year veteran whose most recent stops include backing up Stroud in Houston and Josh Allen in Buffalo. “There is so much value in that,” Smith says. “Case is great at preparing. He’s competitive as hell. It’ll be so great for Caleb to be around that every day.”

With 66 NFL starts to his name, Case Keenum (right) brings a wealth of experience to share with 2024 No. 1 pick Caleb Williams (left). (Michael Reaves / Getty Images)

A mentor like Keenum could prove the difference in a young quarterback keeping his job and losing it. While the position gets younger — the average age of Week 1 starters last fall was 27.6, the lowest in 67 years — the leash is getting shorter. Patience is thinning, from ownership on down. It’s why Manning and Aikman are convinced, had they played in today’s era, their rocky rookie seasons would’ve earned them a spot on the bench.

For how long, they’re not sure.

‘The pressure to play the kid is real. It just is.’

Looking back, Ballard wishes he’d resisted that pressure and kept Richardson on the bench as a raw 21-year-old rookie. Instead the team let his talent cloud its judgment.

“There’s an expectation,” Ballard says. Draft a quarterback high, and the clock starts.

The Colts didn’t make Richardson earn the job, didn’t make him prove he was ready for the role — the QB competition they staged with Gardner Minshew that August was a sham — and it’s a decision Ballard now regrets. Richardson injured his throwing shoulder four games in and was shelved for the year.

He lost more than playing time; since he was away from the building, Richardson didn’t get the chance to build the daily habits needed to start in the NFL. A year later, his preparation slipped. His coaches noticed. Some teammates, too. “He was drowning,” Ballard later admitted.

Richardson was benched.

“Extremely talented, good kid,” Ballard said this summer. “He just doesn’t know yet.”

Smith has seen it play out too many times: Teams preach patience, then can’t help themselves. “They have this shiny new toy and they can’t wait to unwrap it. And so often it’s the wrong decision.”

Unwrapping that toy too early comes with serious risk, especially if the pieces around the quarterback aren’t in place. It often starts with the offensive line. Young quarterbacks playing under duress develop bad habits, and those habits can be hard to break. Scars, Arians calls them.

“And some of these guys never get those scars off,” he says.

Smith saw it watching Williams’ tape last season in Chicago. The Bears’ rookie was sacked a league-high 68 times. Some of that was a leaky line. Most of it was on Williams holding onto the ball too long.

Before him, it was Zach Wilson in New York. And before Wilson, it was Sam Darnold in New York. “The Jets just threw both of them in there right away, crossed their fingers and hoped for the best,” Smith says. “They didn’t have a plan, and they didn’t have any patience.”

The Jets would later admit their biggest mistake with Wilson was not giving him any real competition for the starting job as a rookie. They were in a race to find out if he was the answer. Then, when he started to struggle, the team tried to downplay it, acting as if everything was on track.

It wasn’t. The coaching staff lost faith in him. The firestorm intensified.

It’s hard for young quarterbacks to come back from that. Some do, reviving their careers at a later stop — Baker Mayfield in Tampa Bay, Geno Smith in Seattle, Darnold last season in Minnesota. Plenty never live up to their draft billing. A cloud hangs over them for the rest of their time in the NFL.

“When I started out, there weren’t some talking heads ripping me on TV 24/7,” Aikman says. “Now you’ve got it all day on every sports channel, and the owners are listening to this, the GMs are listening to this, and the coaches are seeing it, too. There’s just so much more these guys have to learn how to handle.”

“It used to be newspapers, right?” Hasselbeck says. “An owner or coach would make a decision based on something they read in the newspaper. Now people are making depth chart decisions based on their social media feed. I have no doubt that actually happens.”

All of which can leave a young quarterback, in Aikman’s words, “in a really dark place.” Like Young was as a rookie in Carolina. Like Williams was last season in Chicago. Like so many Jets quarterbacks over the years.

“It doesn’t matter how much money you’re making, and it doesn’t matter how much success you had in college,” Aikman says. “For the real competitors, if you’re struggling and the offense is a mess and the team is losing, you’re absolutely miserable.”

On paper, Manning’s rookie season with the Colts was miserable. He finished with a league-high 28 interceptions, a rookie record that still stands, and the Colts won just three games. He remembers actually wanting the coaches to bench him during his second game, a 28-7 loss to the Patriots. He threw three picks in the first three quarters, and his confidence was shaken. “I didn’t wanna end the day with five or six,” Manning admits now.

But they didn’t. “You’re staying in,” his head coach, Jim Mora, told him on the sideline that day. “We’re not going to win this game, but you need to figure some things out.”

The Colts had a plan, one handed down by general manager Bill Polian before the season. “Don’t let 18 get hit, period,” Polian told the coaching staff. He knew if Manning wasn’t getting the crap beaten out of him every week, eventually, the light would come on.

It meant reworking the offense and often keeping two tight ends in to block. It meant fewer receivers open down the field, and inevitably, more interceptions. But slowly, the staff began to coach Manning through his early struggles. “I had to tell him a million times the punter was his friend,” Arians, Manning’s first position coach, remembers.

One thing the QB remains grateful for: The staff never blinked. Their belief in him remained unshaken, even as his mistakes piled up. Manning knows he wouldn’t have been afforded the same patience had he entered the draft a year earlier, in 1997, when the Jets and their hard-driving coach, Parcells, owned the top pick.

“There’s no way I throw 28 interceptions in New York,” Manning says. “Because Parcells would’ve killed me first.”

(Illustration: Eamonn Dalton / The Athletic; photos: Jared C. Tilton, Michael Reaves, Michael Owens / Getty Images)