In his new collection Night Watch; poems, poet Kevin Young attends to as seemingly disparate topics: the moon, Dante’s Divine Comedy, birds, conjoined twin singers made into a freak show act, graves, flowers. This is made manifest through four sections (two comprising the majority of the book). By this description Night Watch appears to be a book concerning the wonders of the quotidian or the darkness of humanity. As in the section on Millie and Christine McCoy, enslaved conjoined twins who sang in shows in the United States. After a life of forced medical scrutiny and freak show displays, their liberation brings them the opportunity to perform around Europe and their nation that had previously kept them enslaved.

As with his other writing on historical figures (I think especially of my fan favorite, Ardency), Young plumbs some of the most shameful parts of our nation’s history and society’s violences and holds them up to the light. “Millie-Christine,” as they were singular, are allowed voice, interiority, and nuance in these poems. “It is our mind / doctors without schooling fail / to mention,” they say.

Yet, above all, Night Watch is a book defined by grief and the existential trembling before the precipice of mortality and how we bear witness to loss. It is dedicated to three loved ones Young lost a year apart. “We were both / with all our grief already in us,” he writes, “like teeth.” Young’s interrogation of death and what is after is made most explicit in the series of poems in conversation with the Inferno (which began as a dialog of poems with Robin Coste Lewis responding to Robert Rauschenberg’s “Dante drawings”). Through these pages we descend with Young into the circles of hell, walk with the devil, see how the living contend with the dead (or don’t). The moon looks down like a terrible eye at what humans have wrought, how we grope around for meaning. “When I go // don’t dare sing Amazing / Grace,” Young writes, “that tune / some slaveholder wrote // while at sea, the National / Anthem of suffering.” In its starred review, Publishers Weekly writes, “This elegant volume deepens the body of work by a significant American poet.”

Young tells us: “Most but not all of my to-be-read pile is made up of new and older books related to the next nonfiction history I’m working on, which starts in expatriate Paris between the World Wars; it ends in postwar Paris and stateside in Harlem. Writers like Baldwin, Beckett, and Hughes figure prominently—and are just great to read and read about. I’m looking forward to diving further into the others, including the latest translation of Rumi.”

*

Rumi (tr. Haleh Liza Gafori), Water

Lit Hub’s own Christopher Spaide recommended this new translation a few months ago, writing, “Water, for Gafori’s Rumi, is a versatile, metamorphosing substance, here a fountain, there a torrent, alternately refreshing and engulfing us, extinguishing our passions and cleaning us up: ‘You can’t put out fire, dear boy, / with another fire. // You can’t wash my heart’s open wound / with another’s blood.’ … Like the most engaging playlists, Gafori’s selection boasts idiosyncratic connections and ear-catching tempo changes, from sequences and litanies to unimprovably terse epigrams.”

Samuel Beckett, Watt

“In the summer of 1942, Samuel Beckett and his partner Suzanne Dechevaux-Dumesnil fled their apartment in the German-occupied city of Paris,” writes Jon Michaud at the New Yorker. “Beckett and Dechevaux-Dumesnil rented quarters in a house on the edge of town and proceeded to wait out the war. It was a long and difficult wait. Beckett, prone to anxiety, suffered a mental breakdown… He also labored on a novel, Watt,’ which he’d begun the previous year, in Paris, and which, he said, provided him ‘a means of staying sane.’”

Mavis Gallant, Paris Notebooks

In its starred review, Publishers Weekly notes, “This riveting compendium by Gallant (1922–2014), originally published in 1988 and long out-of-print, brings together the short story writer’s nonfiction from her time living as a Canadian expat in Paris in the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s… Gallant follows in the footsteps of fellow expats Gertrude Stein and James Baldwin in offering astute outsider observations on French literature and culture, marrying trenchant analysis with sinewy prose. This elegantly captures a changing France reckoning with the cultural revolutions of the mid-20th century.”

Robin Givhan, The Battle of Versailles: The Night American Fashion Stumbled into the Spotlight and Made History

The Museum at FIT interviewed Givhan on this book, in which she states, “I think The Battle of Versailles captured the sense of transformation that was such a part of the 1970s. Each of the American designers, in their own way, reflected change. Anne Klein captured the new feminism. Halston was part of the rise of celebrity culture. Bill Blass and Oscar de la Renta both were examples of the distance that American designers and the American fashion industry had come. Stephen Burrows spoke to the social liberation. And certainly the black models—and their impact on the show and influence on the other models—captured the tumultuous racial climate.”

Jack Kerouac, On the Road: The Original Scroll (ed. Howard Cunnell)

Kerouac spent a few years roving around the US with Neal Cassady in mid-20th century America and hanging out with the Beats. Kerouac famously wrote this roman à clef in a three-week burst in Manhattan, its format the author dubbed “the scroll.” As he clacked away, Kerouac taped sheets of tracing paper together and ran them through his typewriter. The single-spaced paragraph-break-free text goes for 120 feet, a talisman of American expansiveness and spontaneity.

The Selected Letters of Langston Hughes, Eds. Arnold Rampersad & David Roessel

In an interview at NPR, Rampersad says of this co-edited collection, “The letters show [Hughes], you know, reaching out to other writers. And what is characteristic of Hughes’s correspondence is how quickly he is willing to turn the other cheek. And he defends the right of people not to like his work and not to like him and to turn on him, as several writers did. A few of them thought he wasn’t complicated enough in his writing – he wasn’t profound enough. And he said, well, I do what I do. I know what I’m trying to achieve with my writing.”

Heidi Ardizzone, The Illuminated Life: Belle da Costa Greene’s Journey from Prejudice to Privilege

Caroline Weber writes in her 2007 New York Times review, “[Greene] was the child of ‘two African-American parents of mixed ancestry,’ and her birth certificate identified her as ‘colored.’ But this label did not square with her ambitions. From a young age, she had a ‘fascination with illuminated manuscripts’ and dreamed of becoming a librarian. In 1906, a series of fortuitous circumstances catapulted Greene into her dream job: helping the financier J. Pierpont Morgan to organize his legendary collection of rare books and manuscripts. Executing her duties with talent and zeal, Greene became ‘arguably the most powerful woman in the New York art and book world.’”

Nicholas Boggs, Baldwin: A Love Story

Lesley Williams writes in a starred review at Booklist, “In this comprehensive, emotional biography, Boggs positions Baldwin’s romantic history squarely at the center of his literary and political work, chronicling the parallel developments in Baldwn’s art and in his relationships. A perennial outsider due to both his race and his queerness, Baldwin sought acceptance in France…Based on extensive interviews with many Baldwin associates and family members, this is an emotionally rich and complex look at a writer who exemplifies the impossibility of separating the personal from the political.”

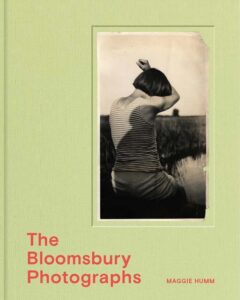

Maggie Humm, The Bloomsbury Photographs

“The Bloomsbury Photographs takes up where Humm’s earlier book Modernist Women and Visual Cultures: Virginia Woolf, Vanessa Bell, photography and cinema (2002) leaves off, and can be read as an expanded and revised edition,” writes Vanessa Curtis at TLS. “The book is divided into sections, the first focusing on photographs reproduced from the King’s College albums of Dora Carrington and Lytton Strachey. These will hold a particular interest for the Bloomsbury enthusiast because the majority of them are previously unpublished (an impressive feat, given how often the various archives have been plundered by other biographers). Humm has chosen a strikingly intimate clutch of pictures, some so personal that it feels almost intrusive to look at them.”