It’s been almost a month since Vijay last restocked the supplies in his appliance store in India Square, Jersey City. Sales have been slow and costs have risen rapidly after the United States declared 25% tariffs on goods from India, his country of birth, and where he sources nearly all his store’s items.

But even before Vijay learned how to adapt to the soaring costs, President Donald Trump announced an additional 25% tariff on India as a retaliation for the country’s purchase of Russian oil.

Days after Trump’s announcement, Vijay was still hoping the president would not go through with implementing the additional tariffs on India. “My costs have already risen by over $10,000 in the past month. If he does follow through with his decision, we are doomed,” said Vijay, who preferred sharing only his first name.

Immigration News, Curated

Sign up to get our curation of news, insights on

big stories, job announcements, and events happening in immigration.

Please check your email for further

instructions.

On Aug. 27, the White House did follow through on its 50% tariff decision on India, sending a chill through supply chains and down to storeowners like Vijay. But days later, on Aug. 29, a federal appeals court ruled that Trump’s tariffs were illegal and he does not have the authority to impose the many tariffs he has waged on other countries. Despite the ruling, the president’s tariffs, including those on India, will remain in effect allowing the government to appeal to the Supreme Court.

Touhid Azad sips a cup of chai, in front of New Foods India. Hundreds of thousands of South Asians like Azad are set to be impacted by Trump’s tariffs on Indian imports. Photo: Biplob Kumar Das for Documented.

Touhid Azad sips a cup of chai, in front of New Foods India. Hundreds of thousands of South Asians like Azad are set to be impacted by Trump’s tariffs on Indian imports. Photo: Biplob Kumar Das for Documented.

Across the Hudson River, Mohammed Alam said he has been feeling the same anxieties.

Alam, who moved to New York City from Bangladesh about 30 years ago, owns New Foods India in the India Bazaar of Kips Bay, Manhattan, a popular destination for South Asians seeking a specific spice or a snack from their homeland.

But unlike Vijay, Alam said he doesn’t have the luxury of waiting for his stocks to sell out, since his groceries have a short shelf life. The cost of his supplies has risen by 30% since tariffs against India first went into effect.

“Eighty percent of my items are shipped from India,” he said in Bengali. “My last bill was about $16,000. And today I will have to pay more than $20,000.”

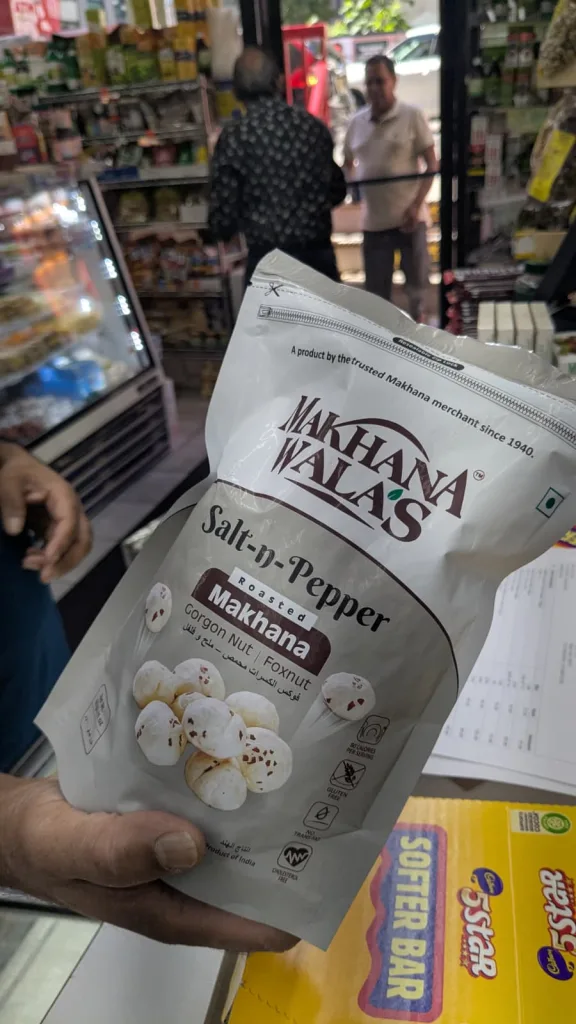

Alam pointed to the popular snack Makhana Wala’s, a roasted gorgon nut shipped from Pune, India, as an example. He used to sell the snack at 99 cents up until the end of August. After he received his latest invoice on Aug. 25, Alam found the importer had nearly doubled the price to $2.35 per packet — a 137% increase. He decided he would sell the snack for $2 instead and absorb the 35 cents himself, incurring a net loss.

“I don’t want to lose customers by increasing prices all of a sudden. But the fact is, I am paying for some of these supplies myself,” Alam said.

Snacks like fried gorgon nuts, produced, packaged, and imported from India, are twice as expensive compared to a month ago. Photo: Biplob Kumar Das for Documented.

Snacks like fried gorgon nuts, produced, packaged, and imported from India, are twice as expensive compared to a month ago. Photo: Biplob Kumar Das for Documented.

President Trump said his tariff policies would incentivize companies to open industries in the U.S. and bring back manufacturing jobs. However, many economists have said Trump’s tariffs cannot bring manufacturing jobs back to the U.S. the way he envisions. Instead, the cost of high import duties is being pushed onto American importers, retailers, and the consumer.

Jonathan Ernest, an economist and professor at Case Western Reserve University says the higher cost could be disastrous for small businesses. “We just don’t have the capacity to onshore a lot of manufacturing jobs,” Ernest said. “Maybe some sectors like microchips and steel, but even then, American labor is way more expensive than other manufacturing hubs.”

Also Read: SNAP Cuts From ‘Big Beautiful Bill’ Threaten Chinatown Businesses

Storeowners like Vijay and Alam had been clinging to hope that the U.S. would strike a deal with India, as it has done with many other major economic partners. But reports suggest the trade talks, which were initially scheduled for Aug. 25, are now indefinitely postponed.

South Asian storeowners say the consequences could be dire as they source most of their products from India, particularly to cater to customers from Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, and Nepali communities. In New York City, there are nearly a half a million South Asians who could also be affected by the rising cost of groceries.

Even before the tariffs on India came into effect, Vijay had to foot the bill for imported steel appliances, which make up more than half of his store. The White House had declared a 50% tariff on all steel imports in June. The tariffs on India have led to costs rising even more.

“Look at the tawas [flat pans], pressure cookers, they are just lying around. There is no one to buy and I can’t get them for any cheaper from here,” he said.

Pans used to cook rotis or flatbread are difficult to find in popular U.S. stores like Target or Walmart, and customers turn to businesses like Vijay’s for their specialized needs.

Pans used to cook rotis or flatbread are difficult to find in popular U.S. stores like Target or Walmart. Photo: Biplob Kumar Das for Documented.

Pans used to cook rotis or flatbread are difficult to find in popular U.S. stores like Target or Walmart. Photo: Biplob Kumar Das for Documented.

“Tariffs are having a negative impact on businesses across the board in the U.S. But the impact on immigrant storeowners is devastatingly high as compared to a Walmart or a Target,” said David Kallick, an economist and director at the Immigration Research Initiative. “When a business is structured around specialized goods coming from a specific region, having an arbitrarily high tariff is really destructive to your business.”

In Jackson Heights, Queens, which is set to be abuzz with several upcoming South Asian festivals, Sunita Kanwar’s jewelry store, Shri Krishna Jewelers, is glittering with Indian gold and diamond ornaments as old Bollywood songs play on loop. But she’s uncertain what the festive season will look like for her business.

“Fifty percent tariffs on jewelry will make it out of reach [for customers]. And remember, the importer, the distributor, the wholesaler, everyone is affected. And by the time it gets to us, a $100 item becomes over $200,” she said.

“We give each other gifts during the festivals, and jewelry is a very special gift. But instead of buying a gift, people will just give cash now,” Kanwar said.

Jewelry is among the top imports from India to stores like Shri Krishna Jewelers. Photo: Biplob Kumar Das for Documented.

Jewelry is among the top imports from India to stores like Shri Krishna Jewelers. Photo: Biplob Kumar Das for Documented.

Jewelry is one of the top imports from India, and is almost on par with textiles and appliances. Although profits on jewelry items are usually quite high, Kanwar said her costs have already risen by 30% in the past month.

“I am looking to make just enough to stay afloat,” she said.

Meanwhile, some storeowners have been preparing for a long time to tackle the uncertainty that comes with Trump’s tariff policies.

Manu Khiantani at his South Asian traditional clothing store, India Sari Place. He says he had stocked up his supplies in anticipation of tariffs against India. Photo: Biplob Kumar Das for Documented.

Manu Khiantani at his South Asian traditional clothing store, India Sari Place. He says he had stocked up his supplies in anticipation of tariffs against India. Photo: Biplob Kumar Das for Documented.

Across the street from Kanwar, Manu Khiantani owns the 45-year-old store India Sari Place, which offers a range of Indian traditional women’s clothing, including bridal wear.

“We had placed higher orders than usual and stocked up a lot in the past months. Even then, we had to pay over 10% higher on our latest shipment,” he said.

Khiantani said Trump’s tariff policy has been a major source of anxiety for him, and he is nervous his clothing stock won’t outlive Trump’s 50% tariff on India.

In Manhattan’s India Bazaar, Ishwari Keller owns a souvenir shop called Vintage India NYC. She said she’s worried about how much her distributor is going to charge in the next monthly invoice. She disagrees with the premise that American businesses stand to gain from Trump’s tariff policies.

“The President has to remember that nothing is 100% American. Every product will have some parts that come from some other part of the world. The world economy is one unit, and everybody has to function as a unit.”