The ideal habitat of the Eastern hellbender that Tracy Davids described was pretty much what she saw on Tuesday morning as she stood ankle-deep in the Davidson River.

“Relatively shallow, fast-moving, highly oxygenated water because (hellbenders) breathe through their skin,” said Davids, senior southeast representative for the Defenders of Wildlife environmental organization. “They also need large flat rocks for cover and nesting.”

And trees, she said, such as the vast stands surrounding the Davidson in the Pisgah National Forest that filter silt and sand from runoff – the greatest threat to the survival of the largest salamanders in North America – and the beech, sycamores, and white oaks that formed a green arch over the riffles upstream from where Davids stood.

“Look at the tree cover here. This is great,” she said. “This is keeping the stream cold, shaded.”

Tracy Davids, senior southeast representative for the Defenders of Wildlife, wades through the Davidson River while explaining the hellbender breeding season. // Watchdog photo by Katie Linsky Shaw

Tracy Davids, senior southeast representative for the Defenders of Wildlife, wades through the Davidson River while explaining the hellbender breeding season. // Watchdog photo by Katie Linsky Shaw

But because of changes in federal policy, even this prime, protected hellbender habitat in Pisgah is in danger, environmental advocates say – so much so that this beloved icon of Southern Appalachia is now emerging as a symbol of the unraveling safety net for vulnerable wildlife.

Just nine months ago, the prospects of the ancient species’ survival brightened notably when the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) formally backed the listing of hellbenders as federally endangered.

But while the job of finalizing that listing is in the hands of that agency, it is also backing rule changes that environmental advocates say would render this status all but meaningless.

In June, the service published a proposal to rescind the decades-old Roadless Rule covering vast swaths of federal land, including 172,000 acres in North Carolina. This would allow two of the main generators of stream-clogging sediment – logging and road building – in formerly roadless tracts in the Pisgah and Nantahala national forests, the 2023 management plan for which already called for a nearly six-fold expansion in the acreage open to timber harvests.

The promotion of logging and other revenue-generating activity has also been used to justify a proposal carrying an even greater potential threat to endangered wildlife, environmentalists say.

In April, the FWS published a plan to remove habitat destruction from the 1973 Endangered Species Act’s (ESA) definition of “harm” to listed animals, limiting their protection under the law to preventing the direct injuring or killing of animals and their removal from their natural surroundings.

A federal official touted the elimination of the Roadless Rule as “removing absurd obstacles to common-sense management of our natural resources,” and the proposed amendment to the ESA says it is an overdue corrective to a burdensome and inaccurate interpretation of the law.

But habitat loss is the main threat to about 90 percent of listed plant and animal species, said Ben Prater, the Defenders’ southeast program director. And hellbenders are an especially clear example of a creature dependent on – and representative of – wild areas that humans also happen to love, said Will Harlan, regional director of the Center for Biological Diversity.

“Previously, we felt somewhat assured that many of the most robust hellbender populations were on national forest lands in western North Carolina,” Harlan said. “But now we’re very worried, because the Forest Service is actively pursuing aggressive timber targets that are unprecedented in scale and will directly harm hellbenders.”

The “endearing” snot otter

What is it about hellbenders? Why are people so taken with a creature that the wildlife service’s Species Status Assessment report described as having “small … lidless” eyes, drab coloration, and bodies covered with protective “mucus.”

Why was an animal commonly known as the “snot otter,” recently adopted as the mascot of an Asheville charter school? Why did last weekend’s Hellbender Festival in Spruce Pine draw such throngs of attendees that they cleared out the Defenders’ supply of education material by mid-afternoon?

It’s partly because the physical features described in the assessment report – which formed the scientific basis for the proposal to list the species as endangered – are testament to its ancient origins, Harlan said.

“They’ve been around for tens of millions of years,” he said, “and they look like it.”

“They’re primordial,” he said. “They breathe through their wrinkled, folded, flappy skin. They have these amazing grip pads on their toes that enable them to cling to rocks and survive through catastrophic flooding like (Tropical Storm) Helene. They also have this really unique facial feature where they look like they’re smiling. They’ve got these tiny, beady eyes and this smirk that just makes them so endearing.”

So does reproductive behavior that flips the gendered stereotype embodied by protective mama bears.

“The males are den masters,” Harlan said. “They spend months guarding the fertilized eggs until they hatch, and they are phenomenally committed to that job. They will stay beneath those boulders to protect their eggs for months at a time.”

Hellbenders are efficient predators and such ruthless competitors that the males’ mating-season battles over territory are a possible source of their names, Prater said on the Tuesday visit to the Davidson.

“They’ll actually lock on each other’s jaws and just swirl around,” he said. “All of a sudden there’s this roiling, boiling hell coming out of the water.”

Ben Prater, Defenders of Wildlife’s southeast program director, explains the additional protections hellbenders would receive under the Endangered Species Act — if it is not weakened by the proposed rule change. // Watchdog video by Katie Linsky Shaw

But for much of the rest of the year, they serve as a powerful reminder of the benefits of living what Hans Lohmeyer, Conserving Carolina’s stewardship manager, called a “docile” lifestyle.

As a grad student, Lohmeyer took part in a study measuring how much the “primarily” nocturnal animals move around at night.

Not all that much, the study found. Even in the darkness, he said, they live protected under large rocks in streambeds, waiting to snag prey such as crayfish carried by currents to the openings of their downstream-facing lairs.

“They weren’t, like, running around everywhere at night when everyone else was sleeping,” he said.

This helps explain both the species’ astonishingly long lifespan – potentially more than 50 years, according to one study cited by the assessment – and their size; because they grow throughout their lives, only the passage of decades allows them to reach lengths of more than two feet.

“When you think of it, kind of like in the sense of a turtle, they’re much more likely to live longer because they’re not exerting life force constantly and forcing their metabolism and heart to continue to keep up with that,” Lohmeyer said. “It’s definitely an evolutionary strategy that makes sense for them.”

Habitat loss, population decline

Or it did before logging, road building, water pollution and development began to destroy their habitat.

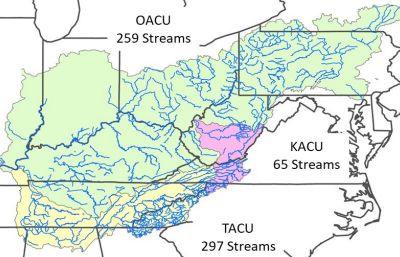

These required surroundings once extended across parts of 15 states, according to the assessment report, which documented 626 historic populations from northern Alabama to western New York state.

Scientists returning to these locations for the assessment found that 76 percent of these communities are “thought to be either extirpated or declining,” the report said.

Only 90 of the remaining populations were classified in the healthiest category, “stable and recruiting,” the report said, and precisely half of those groups, 45, lie within the Tennessee River Valley – most of them, by far, in the mountains of western North Carolina.

The clear, cool streams of the highest Appalachians were always home to the densest documented populations of hellbenders, Harlan said, but their continued health here is largely due to the protection offered by public land ownership and management.

“The Pisgah and Nantahala national forests are home of the most robust populations of hellbenders anywhere on the planet,” Harlan said. “This is where they are doing best and where they have the best chance of surviving.”

A map shows the historical range of the Eastern hellbender. Note the dense concentration of populations in the waterways of western North Carolina. // Image courtesy of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Eastern Hellbender Species Status Assessment Report

A map shows the historical range of the Eastern hellbender. Note the dense concentration of populations in the waterways of western North Carolina. // Image courtesy of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Eastern Hellbender Species Status Assessment Report

Elsewhere in the hellbenders’ range, populations have declined or succumbed to what the report lists as the second-greatest threat to their continued survival – “water quality degradation” from sources such as “agricultural runoff, coal mining activities, and unpermitted industrial discharges.”

Spills of toxic waste have been directly implicated in hellbender die-offs in heavily industrialized regions of its range, including the drainage basins of the Ohio River and the Kanawha River in West Virginia, the report says.

Waterways running through privately owned land are subject to organic waste contamination from municipal treatment plants and livestock that saps their dissolved oxygen, according to the assessment. And clearing land for development allows direct sun exposure, exacerbating the warming effects of climate change.

Development also generates sedimentation, which the report calls the “primary stressor of the Eastern hellbender.” That’s especially true in the national forests where hellbenders are largely protected from other human-caused threats, said Davids, the Defenders representative, who was able to show the negative impact of clay, silt and sand carried by runoff.

The likely source was Pisgah’s degraded gravel roads, a small portion of the nation’s $8.6 billion backlog of inadequately maintained forest tracks.

With fewer exposed rocks to agitate the water, its dissolved oxygen levels have declined. Sediment blankets the habitat of the crayfish and insects hellbenders prey upon. It seals the openings beneath rocks that the salamanders are able to find, but not dig out, with their short limbs.

These have evolved to cling to rocks, she said. “They aren’t made for excavating.”

Undermining protection?

The proposals to eliminate the Roadless Rule, change the definition of harm in the ESA and list the hellbenders as endangered are running on parallel tracks.

All have been published on the Federal Register, allowing for public review and comment. None can be finalized until the FWS considers these comments in the context of available scientific data.

An FWS spokesperson contacted by the Asheville Watchdog responded, without allowing the use of her name, that the agency is still pursuing the endangered listing for the hellbender.

For information about the plan to alter the ESA, she provided a link to the published notice on the Register, which says that the interpretation of the law including “habitat modification … runs contrary to the ‘best meaning’ of harm.”

Prime hellbender habitat in the Davidson River. Hellbenders feed and nest under large rocks in clear streams. // Watchdog photo by Katie Linsky Shaw

Prime hellbender habitat in the Davidson River. Hellbenders feed and nest under large rocks in clear streams. // Watchdog photo by Katie Linsky Shaw

Which is, the notice continues, “to … hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect” protected species.

And in August, U.S. Department of Agriculture Secretary Brooke L. Rollins said rescinding the Roadless Rule would remove “burdensome, outdated, one-size-fits-all regulations that not only put people and livelihoods at risk but also stifle economic growth in rural America.”

Though it’s too early to know exactly how the proposed rule changes will play out in Pisgah and Nantahala, Harlan and Prater said, they could greatly curtail current protections.

The new proposed language in the ESA mirrors that of former Justice Antonin Scalia’s dissenting opinion in the 1995 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that affirmed the ESA definition of harm to include destruction of habitat. It would also limit protection to about what the species currently receives under its “relatively toothless” designation as endangered by North Carolina, Harlan said.

On the other hand, if hellbenders are listed federally – far from a certainty, he said, given the agency’s stated opposition to added environmental regulation – the law as currently enforced would require other federal agencies to consult with FWS about plans that potentially impact the species’ habitat.

Take, for example, the expanding logging allowed by the forests’ management plan and potentially allowed by the proposed elimination of the Roadless Rule, he said.

The ESA would mandate the U.S. Forest Service to clear timber harvesting plans with FWS, which wouldn’t prohibit the practice but could restrict logging to certain areas, Harlan said, or “require a 100-foot buffer along a hellbender stream where no logging occurs, to absorb some of the runoff and prevent too much sedimentation.”

Another example is the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA’s) post-Helene removal of debris from waterways such as the upper reaches of the French Broad and Little rivers. Lohmeyer, the Conserving Carolina stewardship manager, has previously said the excesses of the process created an “ecological crisis” that included the destruction of hellbender habitat.

Hellbenders populations that were diminished (but remarkably, not destroyed) by the storm, were further harmed by cleanup crews that, Prater said, “literally rode machines up and down” hellbender streams.

With the law interpreted as it has been for decades – and the hellbenders listed as endangered – Prater said, FEMA would have needed FWS approval for its clearance plans, and “having a listing would have given us additional support to argue against those actions.”

Extinction events

But the larger reason for providing full endangered protection to hellbenders can be traced to another reason the animals are so cherished by the people of western North Carolina, Harlan said.

“They’ve become a symbol of southern Appalachia because they live in our most pristine places, where people love to recreate,” he said.

Where there are hellbenders, there are healthy trout populations, he said; there are clear streams for swimming and kayaking.

“I think they’ve become a source of pride and symbolic of the health and vitality of this region,” he said.

That pride is evident in the public embrace of Defenders’ campaigns to protect hellbenders, such as the one urging visitors to wild areas not to move rocks the animals need for shelter, Davids said.

Ben Prater, Defenders of Wildlife’s Southeast Program Director, explains why the popular activity of rock stacking harms hellbenders and other aquatic creatures. // Watchdog photo by Katie Linsky Shaw

Ben Prater, Defenders of Wildlife’s Southeast Program Director, explains why the popular activity of rock stacking harms hellbenders and other aquatic creatures. // Watchdog photo by Katie Linsky Shaw

And considering the species’ long history, this pride should extend to providing enough protection that it doesn’t die out on our watch, she said.

The lineage of the hellbender can be traced back 150-million years, about half as long ago as the formation of the famously ancient Appalachian Mountains. They or their ancestors lived on earth longer before the extinction of the dinosaurs, roughly 66 million years ago, than they have since. And all the threats to their continued survival – climate change, pollution, development and sedimentation – are far more recent and “man-made,” Davids said.

“Hellbenders survived the last extinction event,” she said. “Whether or not they survive the next one remains to be seen.”

Asheville Watchdog welcomes thoughtful reader comments on this story, which has been republished on our Facebook page. Please submit your comments there.

Asheville Watchdog is a nonprofit news team producing stories that matter to Asheville and Buncombe County. Dan DeWitt is The Watchdog’s deputy managing editor/senior reporter. Email: ddewitt@avlwatchdog.org. The Watchdog’s local reporting is made possible by donations from the community. To show your support for this vital public service go to avlwatchdog.org/support-our-publication/.

Related